This animated map shows why animals can’t survive climate change without our help

As the global climate gets hotter both people and animals will have to adapt to changes in their local environments. However, while people can shed clothes or turn up the A/C, animals have fewer options to maintain the conditions they need to survive. If their home habitats change too much, they’ll be forced to migrate in search of new territory. “Migration” sounds like a simple fix, and in some cases it might be, if not for one big problem: There are, literally, a lot of things in the way.

As the global climate gets hotter both people and animals will have to adapt to changes in their local environments. However, while people can shed clothes or turn up the A/C, animals have fewer options to maintain the conditions they need to survive. If their home habitats change too much, they’ll be forced to migrate in search of new territory. “Migration” sounds like a simple fix, and in some cases it might be, if not for one big problem: There are, literally, a lot of things in the way.

Nearly every path that animals would naturally travel is blocked by roads, fences, houses and other man-made barriers. According to research published earlier this year in PNAS (paywall), “only 41% of natural land area retains enough connectivity to allow plants and animals to maintain climatic parity as the climate warms.” In some parts of the eastern US, as little as 2% of the land remains well-connected.

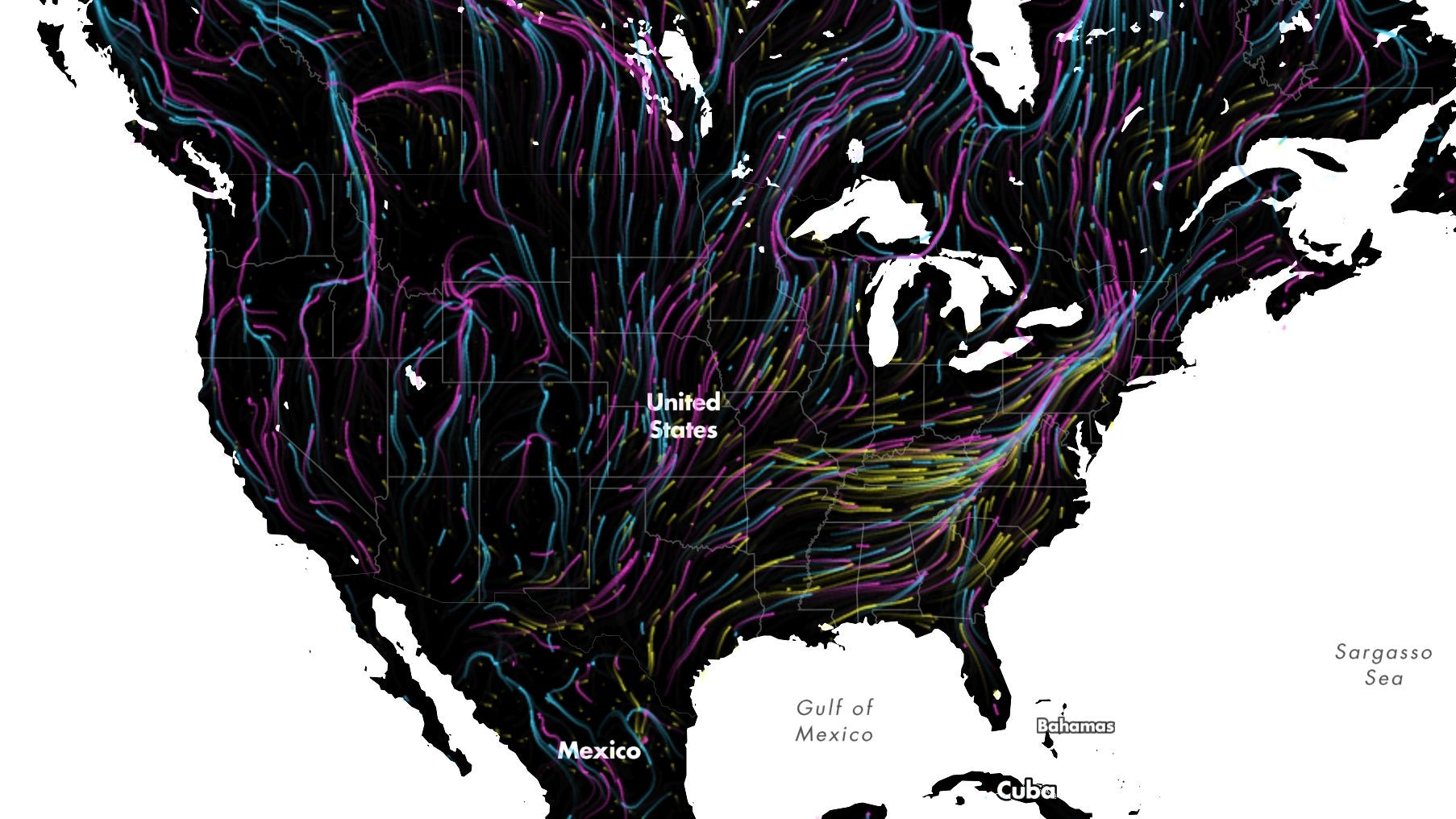

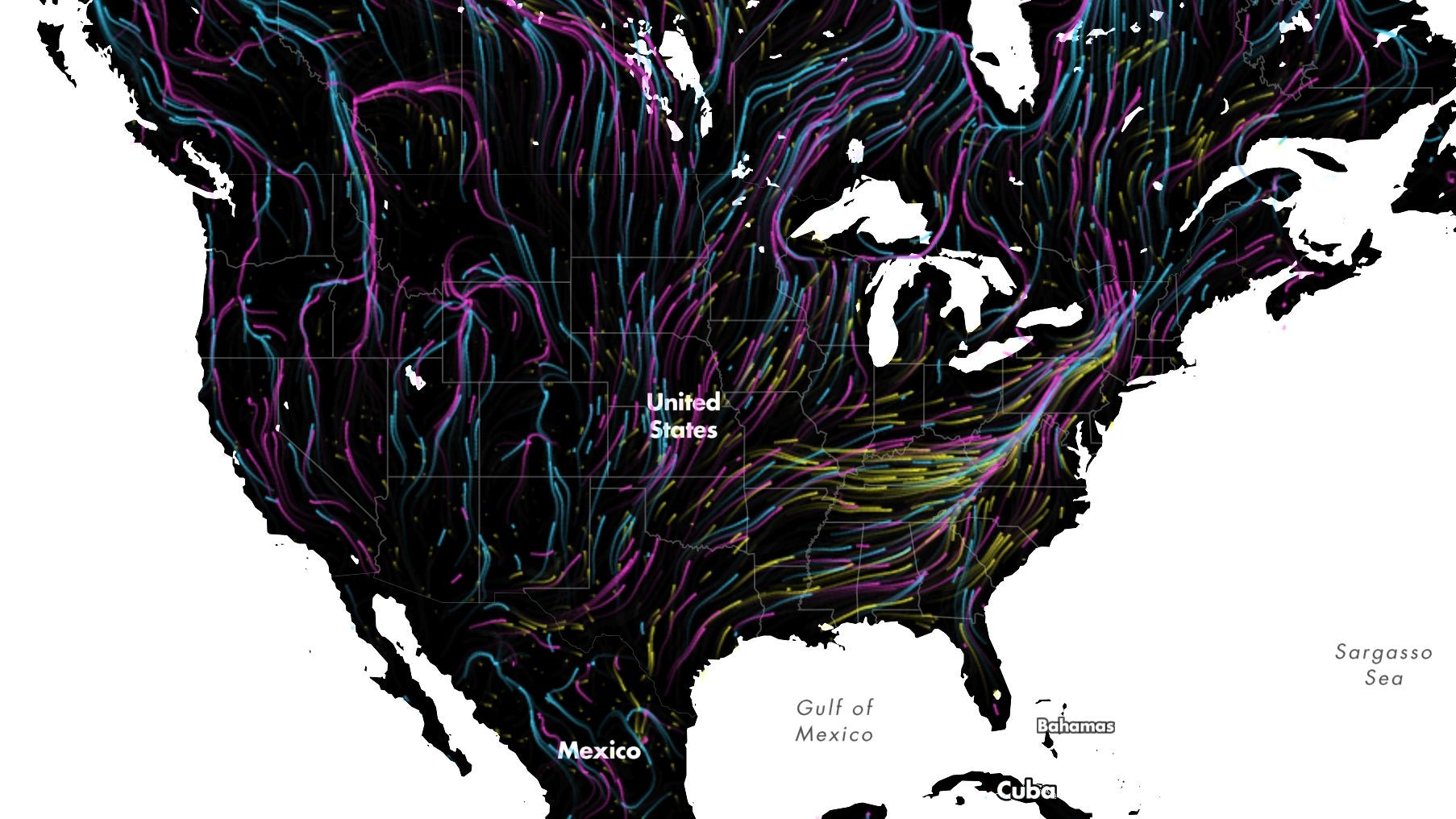

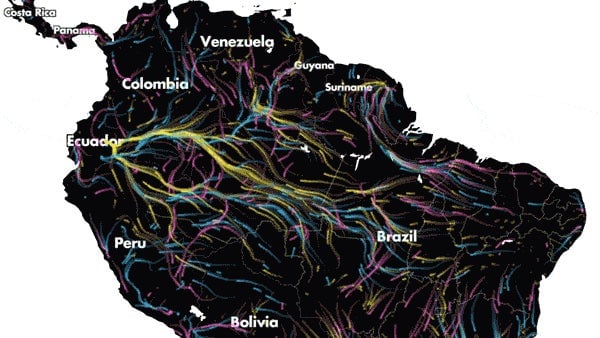

To illustrate the problems this will cause, Nature Conservancy cartographer Dan Majka created an animated map of the paths animals would likely try to follow in order to stay within their ecological niches as the climate changes. Both the map and the PNAS study are driven by data from earlier research (paywall), which used algorithms designed for predicting electricity flow through circuits to estimate the most efficient migration path for each of nearly 3,000 different species across North and South America.

Each line on the map represents the likely migration path for a single species. Pink paths are mammals, blue are birds, and yellow are amphibians. To view the full map, click here.

Migration barriers are not a new problem, nor one that is solely driven by climate change. Animal populations isolated by roads or other barriers are at greater risk of danger from disease or invasive predators. If a species only exists in one location, it could go extinct entirely. The climate change dimension brings new urgency to this issue as it could cause the near-simultaneous, and permanent, need for a large number of species to relocate. Those that are find themselves trapped could simply die out.

Fortunately, some promising solutions to this problem already exist. Many countries have already established wildlife corridors to connect isolated natural regions. Often, these are wide tracts of undeveloped state or federal land that are reserved for animals to travel across; they can also be narrow easements or passageways that bypass human infrastructure.

In Canada, overpasses in Banff National Park allow wolves, bears, deer, and other animals to cross highways. In India, protected lands keep traveling elephants safe. Other corridors don’t require giving up any land at all. In Oslo, a network of rooftop flower pots allows bees to wander across the city.

Though they are certainly not a solution for all our environmental woes, wildlife corridors have the benefit of extensive scientific support. The research suggests that connecting lands separated by 10 km (6.2 miles) or less could increase the total amount of connected land from 41% to 60%.

Sadly, wildlife corridors can also be difficult and expensive to implement. So, as with climate change in general, saving the diversity of animals will require more economic concessions from humans—the animals that created the problems in the first place.