As Hong Kong goes to the polls, why isn’t the Communist Party on the ballot?

Hong Kong

Hong Kong

Nearly twenty years after China resumed sovereignty over the former British colony of Hong Kong, the Chinese Communist Party that rules the rest of the country is still officially non-existent here.

Under the British, the Communist Party was illegal, and banned from registering as a political organization. After the handover in 1997, the Communist Party in Hong Kong has remained underground. As Hong Kong prepares to go to the polls on Sunday (Sept. 4), the Party’s members will not run for elections—but they still have an out-sized influence in the city.

“Everyone knows they are here even if officially they do not exist,” says Martin Lee, the founding chairman of the Democratic Party. “But, they are not popular in Hong Kong.”

The biggest emanation of the Chinese Communist Party here is the Liaison Office of the Central People’s Government—one of the favorite destinations of many pro-democracy rallies—which acts as the highest level representation of the Beijing government in Hong Kong. It is still not, officially, a branch of the Communist party, even if its representatives are all members. But the Party also makes itself felt through the city’s “pro-establishment” political parties, who have been behind many unpopular decisions including an attempt to introduce a new pro-Communist education law and a new election system for chief executive. Opposition to these laws sparked some of the biggest street protests in Hong Kong history, including the Umbrella Movement.

Various officials of the local city government have been suspected at one time or another of being secret members of the underground Communist Party, but nobody has ever come up with an official, verified list. Leung Chun-ying, Hong Kong’s chief executive and top official, has denied several times that he has joined, but rumors about his secret membership never cease.

This makes Hong Kong the rare place under Chinese sovereignty where the suspicion of belonging to the Communist Party has to be vehemently denied.

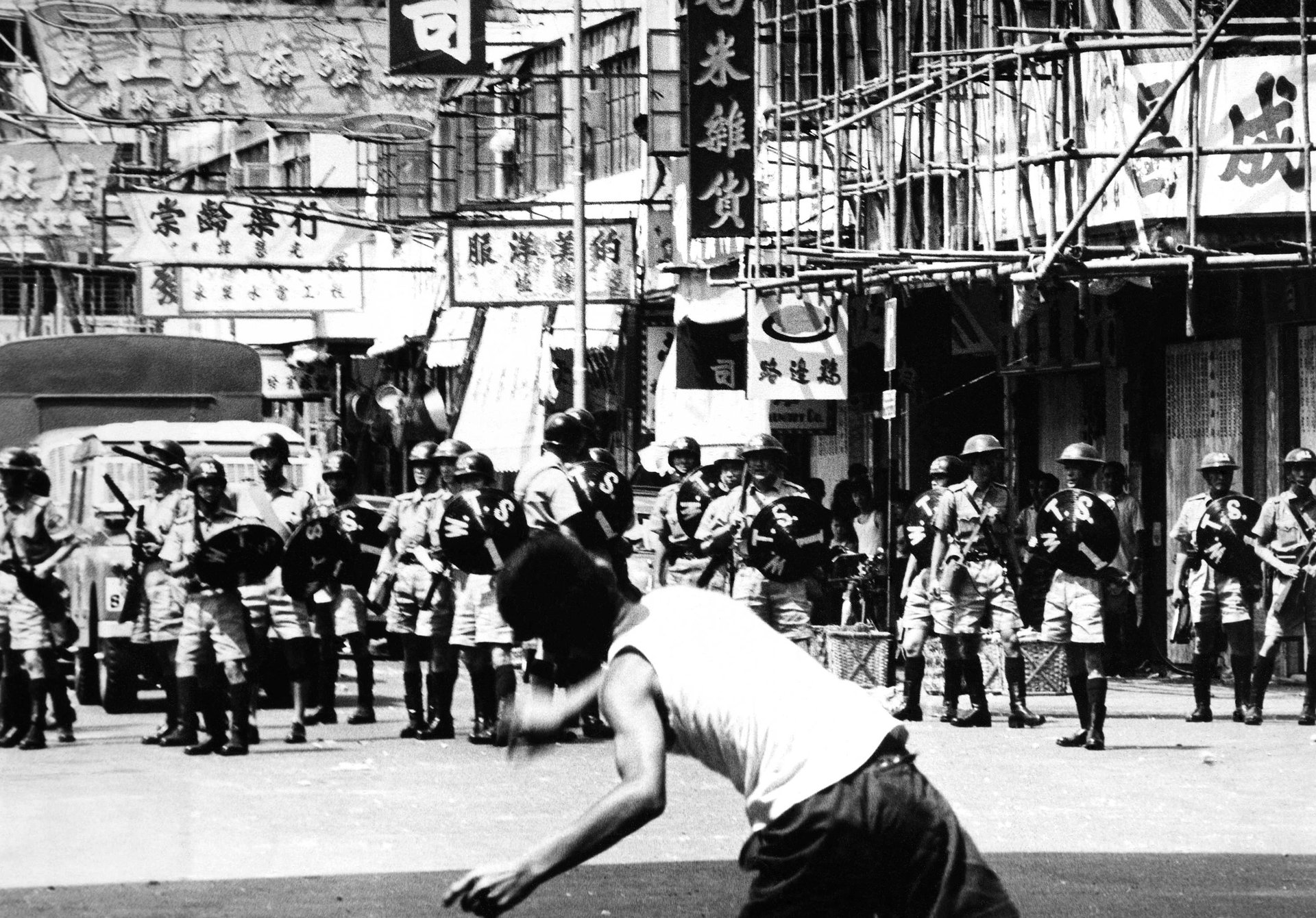

Perhaps it’s no wonder, given the suspicion with which the local population historically regards the Party, from whose persecution and economic duress many have fled through the years to become Hong Kong citizens. The mistrust is widespread, and became entrenched during the 1967 Riots, the most violent Hong Kong ever saw. The riots were openly backed by China, itself in the throes of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution at the time.

The Party has never even registered under the Securities Ordinance, as political parties are supposed to do in Hong Kong. “Why bother registering, when you already have all the power?” asks Lee.

Bao Pu, a publisher and political commentator, says Hong Kong’s underground Communist Party is a “legacy” of the creation of the party in the 1920s. “They treated Hong Kong as an overseas base, and not being close to the central core [in Beijing] meant they were not required to report to the center unless they saw something they thought the Party should know, which they did through private channels.”

Keeping the Party underground makes their work in Hong Kong easier. “The Chinese Communist Party does not want to be registered in Hong Kong and come under local laws,” says Ching Cheong, a Hong Kong journalist who was detained in China a decade ago on espionage charges. “In China, it is above the law. If they registered in Hong Kong, they would have to file [tax] returns, file their membership list, and their financial transactions.”

The ultimate reason the Communist Party may not want to become official in Hong Kong, though, is the possibility that it might be embarrassed.

After all, Hong Kong and the former Portuguese colony of Macau are the only places under Chinese sovereignty where there are partially free elections, which do not exist in the rest of China. If the Communist Party were to run here, they could lose an election. And that would provide a very strange example for the rest of the country.