Edgar Lungu returned to the inaugural podium on Sept. 13, nearly a month after winning Zambia’s presidency. The contested election rocked the normally stable country. Now Lungu has to make good on the promises he made to save the economy.

Zambia’s elections are usually held later in the year, but were brought forward to August ahead of an “inevitable“ deal with the International Monetary Fund, which will result in austerity measures. Even as wrangling over the election result took place, Lungu was in talks with the IMF and agreed to cut fuel and electricity subsidies. Africa’s second biggest copper producer experienced its slowest growth in 17 years in 2015, and its budget deficit grew to 8.1%, according to Bloomberg. Lungu’s government is supposed to start implementing austerity measures in the fourth quarter.

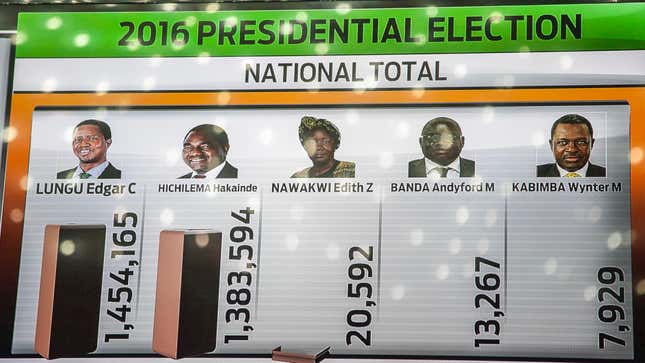

But the continuing challenge from opposition politicians will make his task more difficult. Lungu’s narrow victory—50.35% of the vote, compared to 47.63% for his rival, Hakainde Hichilema—was disputed. A day before the inauguration, Zambia’s supreme court dismissed an appeal by the opposition to postpone the ceremony.

Post-election riots led to the arrest of about 150 people, including another opposition leader, Nevers Mumba, who was detained earlier this week. The run-up to the election also led to a crackdown on independent media that have been critical of Lungu and the ruling Patriotic Front. The opposition also questioned the independence of the Electoral Commission for Zambia and the judiciary that legitimized Lungu’s victory.

As the inauguration went ahead, some Zambians tweeted that Lungu’s suit looked similar to the one he wore to his first inauguration in 2015. If true, that wouldn’t be the only moment of déjà vu. Lungu’s narrow win that year, in a by-election precipitated by the death of president Michael Sata, was also followed by violence. His rise to the top of the Patriotic Front saw Sata’s son and former vice president desert the party.

“You need to win their confidence and I don’t think he scores very highly in that regard ,” former vice president and caretaker president Guy Scott told the Financial Times. “He needs to actually understand quite a lot of economics, and has a tendency to pray to God to sort the economy out.”

Lungu’s response to the tanking currency, the kwacha, was a national day of prayer. The kwacha then staged a miraculous recovery—though metal prices and investor-friendly policy changes, rather than divine intervention, were probably responsible.

And faith hasn’t saved Zambia from rolling electricity blackouts and a drought. Severe weather across the region has made food prices climb as harvests shrink. A bag of maize meal, the country’s staple, cost $5 in February. It now costs as much as $12, according to Reuters. Lungu, and previous presidents, have not been able to wean Zambia’s economy from it’s dependence on copper exports.

The unstable economy is inextricably linked to the political infighting. Zambians have seen four presidents in less than 10 years (two of whom died in office), leaving the country with a fractured political arena and no certain long-term policies. And unprecedented post-election violence has only further eroded investors’ confidence. That will make it hard for Lungu to deliver on his promises.