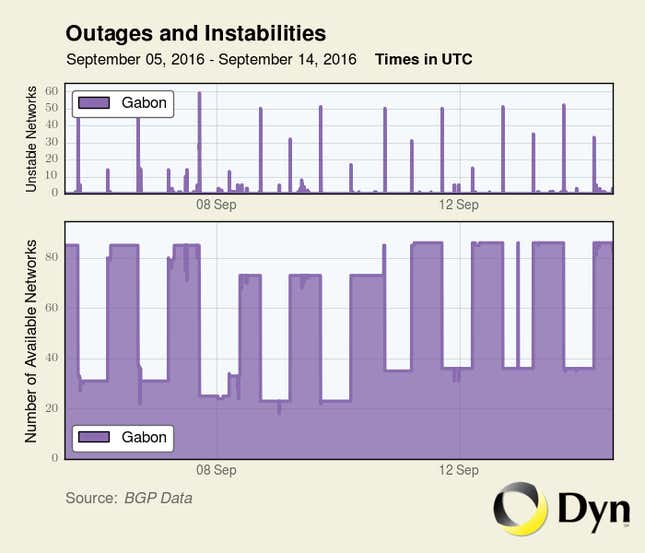

Since early September, the government of Gabon has instituted systematic nightly internet blackouts across the country, a move web analysts say is “unprecedented”. The internet curfews last for about 12 hours, starting from early evening to the early hours of the morning, according to Doug Madory, the director of web analytics firm, Dyn.

The curfew, which started on Sept. 5, was preceded by a 104-hour continuous internet blackout, which began after the controversial results of the presidential election were announced on Aug. 31. The shutdowns were considered the longest countrywide blackouts since Libya went offline during the uprising against Muammar Gaddafi in 2011.

This trend of curfews is indicative of the brewing tensions in Gabon, which is in political limbo since incumbent president Ali Bongo was declared the winner of the election. His rival, the diplomat Jean Ping, has dismissed the results and has demanded a recount. The country’s Constitutional Court is set to issue a judgment next week (Sept. 23) on whether to do a recount of the vote or declare Bongo the official winner. For now, the dispute has led to protests, the burning of the country’s assembly, and the killing of six people.

During the day, the internet in the country functions normally, an attempt by the government, analysts say, to show that life is back to normal. About 91% of the country’s IP addresses are routed through the government-controlled Gabon Telecom. Several people have noted that social media outlets were blocked even when internet access was available.

“The government is most likely allowing internet access during the day to minimize disruptions for businesses while blocking it in the evenings to hinder opposition supporters from plotting against Bongo,” says Maja Bovcon, senior Africa analyst at risk consultancy Verisk Maplecroft. The shutdown, she said, reinforces the belief that the elections were rigged.

On the second day of the blackout (Sept. 1), the UN secretary general Ban Ki-moon called on the government to “immediately restore communications.” The government has however denied cutting off the internet and accused Ping of using the net to spread rumors. Both Bongo and Ping have consistently used Facebook and Twitter to legitimize their political positions and speak to their supporters.

According to Julie Owono, the head of the Africa desk at Internet Without Borders, activists and civil society members have been using various tools to circumvent the shutdown, sharing photos and videos of what’s happening on the ground.