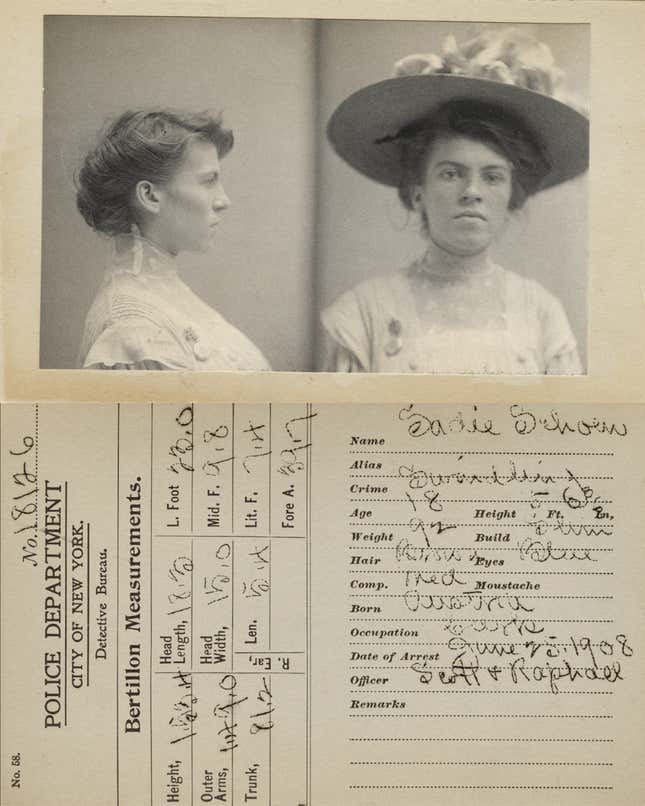

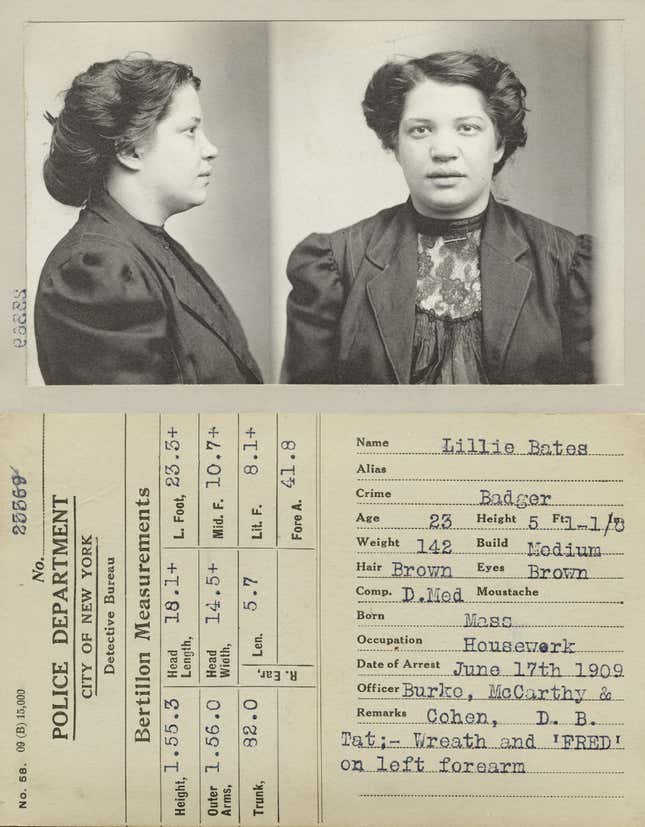

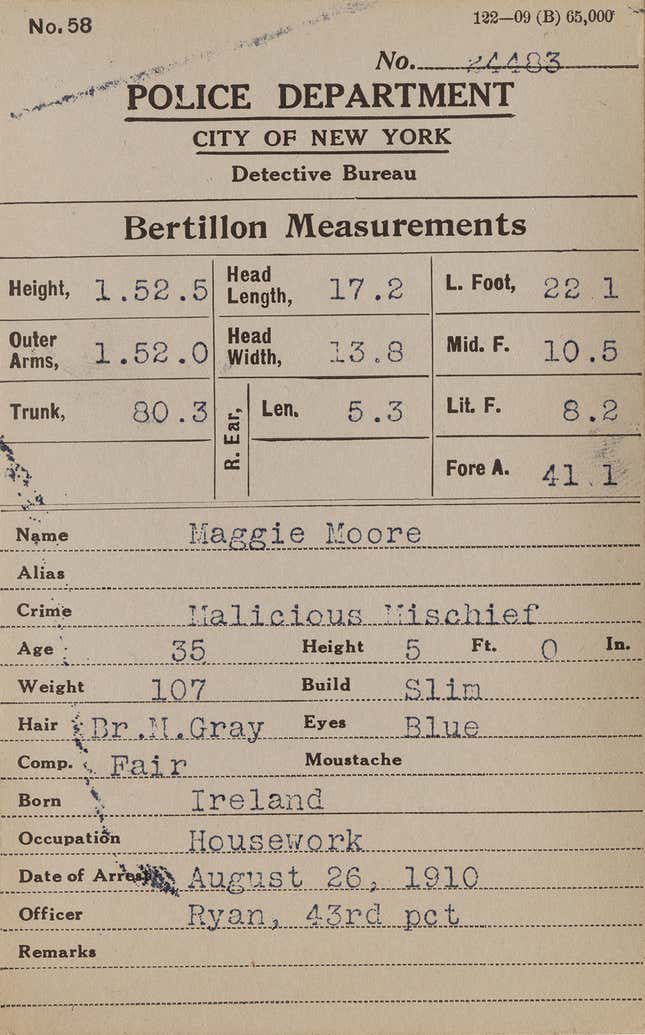

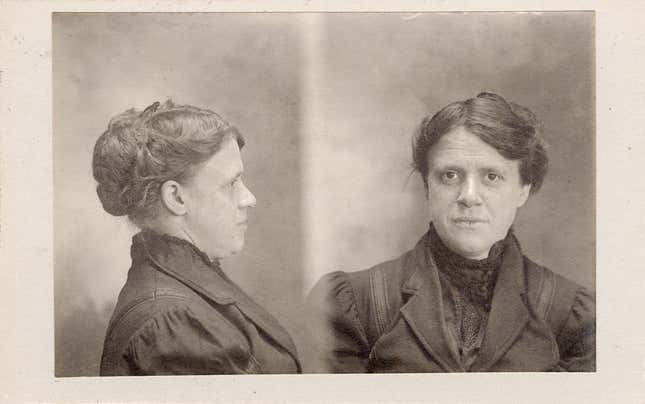

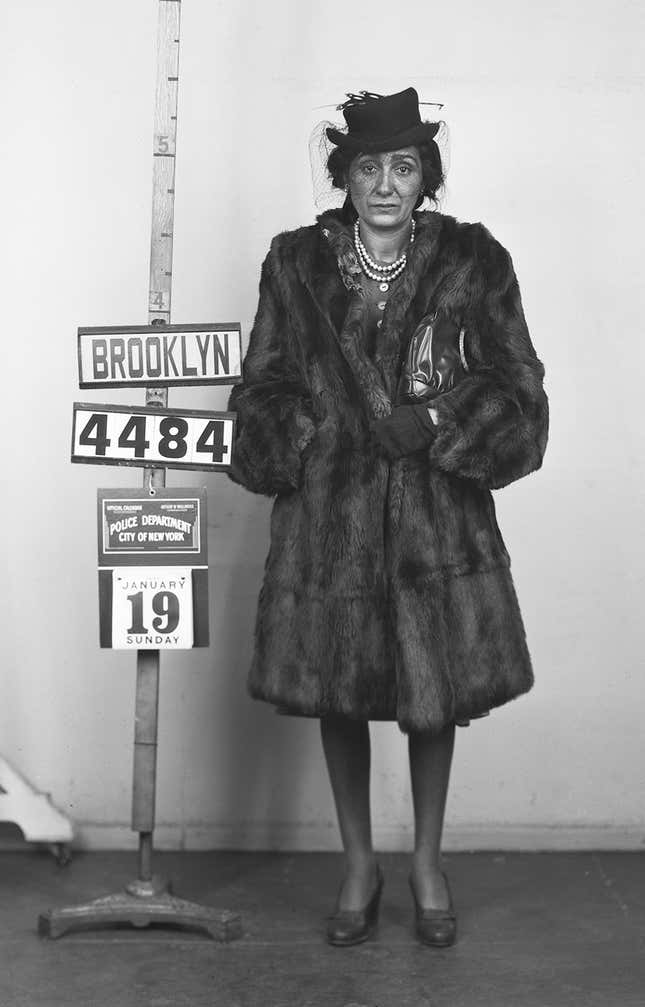

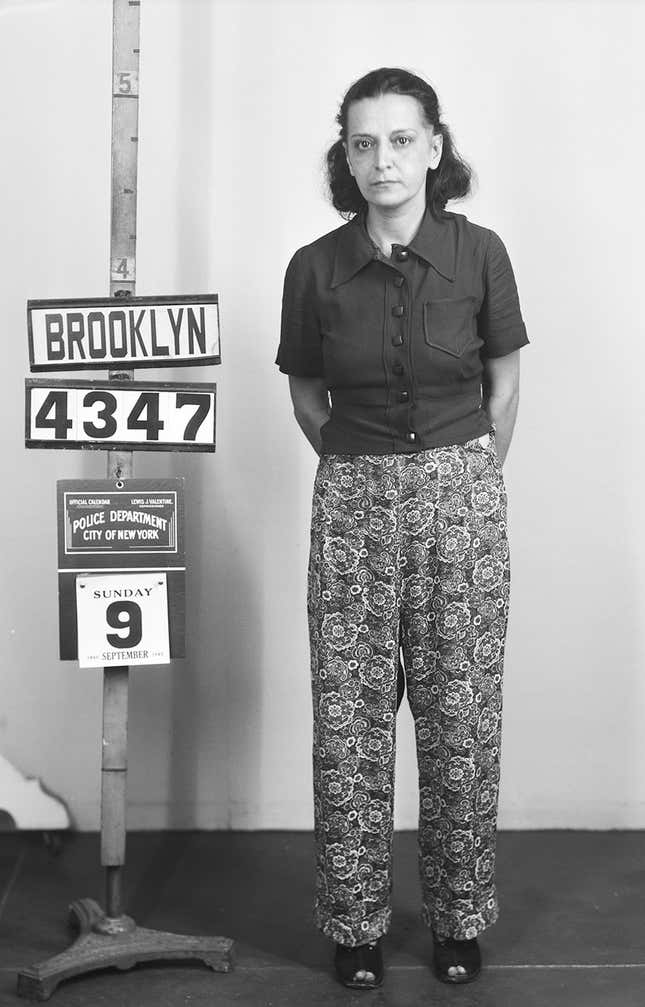

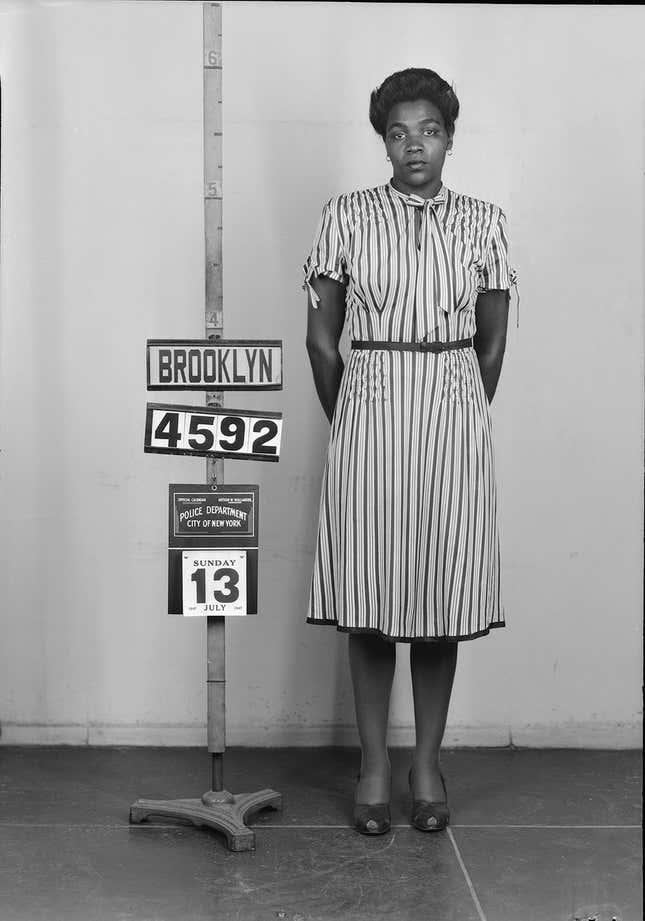

Malicious mischief and “badger” are some of the charges against the women below, whose mugshots were taken at New York police precincts more than 100 years ago. But who would have guessed they were mugshots at all, with subjects sporting fancy flowery hats, fur coats and high heels?

Quinn Berkman, a program coordinator of New York City’s Department of Records, dug these black and white photographs out of the city’s municipal archives, to create the series Pretty Girl Charged with Clever Swindle: Women and Crime in Early 20th-Century New York City, currently on show at New York photo festival Photoville. They are the first generation of standardized mugshots in the US, testament to the history of crime photography.

In 1879, a French police clerk called Alphonse Bertillon (son of a statistician, who had a passion for anthropology) got fed up with his job of indexing inconsistent photographs of suspects. Because identifying information was not standardized, it was difficult to find and prosecute repeat offenders. So Bertillon invented what is now known as the ”Bertillon System” and revolutionized criminology.

Bertillon created the first standardized approach to criminal photography, says Berkman. He wrote down specific mugshot instructions: Suspects had to be photographed from the front, wearing a hat; and then from the side, without a hat. Hats were omnipresent accessories back then, so it was important to be able to identify the person with a hat as well as without. (Not all mugshots here actually include hats though, likely because suspects didn’t have them at the time of booking.) Bertillon also standardized pose, lighting and distance requirements for mugshots.

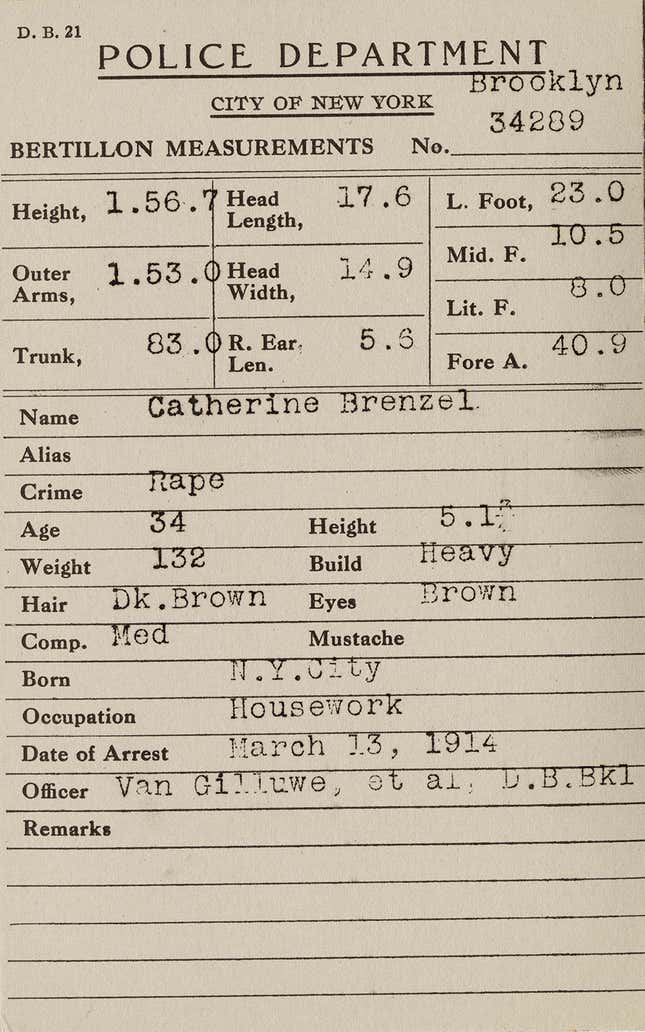

To further classify individuals by physical characteristics, Bertillon also devised a system that recorded eye color, hair color, height, head width, head length, length of left foot, outer forearm, trunk and left middle and little finger.

These measurements were then meticulously noted on small cards called “Bertillon Cards,” which were indexed and archived in a filing system with over 243 categories. This system allowed law enforcement officers to search by physical trait, instead of name. After sifting through tens of thousands of cards to find a small stack that might match the suspect, the individual could finally be confirmed using the mugshot.

The Bertillon system was a success. In 1887, police across the US began adopting Bertillon’s system. In 1893, New York’s superintendent of prisons sent a clerk to Europe to study the radical new system. By 1918, the New York City police department had introduced standing mugshots in the Bertillon style, for repeated offenders and people accused of serious crimes.

But the system was not without flaws. In 1903, a man named Will West was arrested in Kansas. After being measured using the Bertillon system, he was found identical in nearly every way to another man named William West, who had been convicted of murder and was serving a life sentence. There was no proof of any relation. The men were doppelgängers even in real life, but they were eventually distinguished using their fingerprints.

The Bertillon identification system was phased out in the US in 1920, replaced by even more rigorous finger-printing identification methods. What remains, though, is the Bertillon-style mugshot photo we still use today—but strictly without hats.

The exhibition “Pretty Girl Charged with Clever Swindle” is on at NYC Photoville until Sept. 25.