I had spent close to a week in Bangladesh presenting and participating in the Dhaka Literature Festival in November 2015. After the trip I took a few days off to tour Singapore and Malaysia—both of which I fortunately did not require a visa in advance. My return flight to my hometown, Nairobi, would transit through Istanbul. There was an unavoidable 24-hour layover that the airline would compensate me for in the form of a five-star hotel room during my long wait. I got to Istanbul—exhausted and eager to get to my nice cozy hotel room, shower, and sleep off my jetlag before my long trip to Nairobi.

Airline officials assured me that all I needed to do was get my one-day transit visa for Turkey from a little machine. The first question on the screen read “Are you a citizen of the USA, UK, Germany, France… Chile, South Africa?”

I am a Kenyan citizen.

“Are you holding a valid visa for USA, UK, Germany… Chile, South Africa?”

Uhhmm. No. I am generally issued 10-day visas, two-week visas, one-month visas for certain countries if I am very lucky.

The next message on the screen read, “Unfortunately you are not eligible for a transit visa.” Just like that, I realized that my Turkey experience would be lived at the airport. I got back to the information counter sad at the realization that a valid Chilean visa was more readily accepted than my Kenyan passport.

I was led to a huge football stadium of a bedroom—filled with other black people, brown people, and some Arabs – those of us passport undesirables. I was shown my makeshift bed, given a pillow and a thin blanket. “You can stay here ’til your flight, tomorrow.”

It made me think of all the indignities I and so many other Africans suffer at the hands of immigration officials.

The Nigerian writer Elnathan John, who was a Caine Prize finalist, captured it well in a recent series of tweets. “A good African traveler is one who returns. One who leaves Europe or America quickly. The embassies love them. Good African doesn’t move.”

I have been a ‘Good African.’ Back in 2005, I went to the US on a student visa. I graduated with a degree in finance and moved back home after graduation, driven by a passion to work in my own country. I came. I did what I had to do. I was thankful for the opportunity to stay within your borders and when the time to leave came, I left.

So, why is it that every time I want to come back, you still doubt I will leave? Have I not yet proven I have no long-term intentions in your countries? And what if I did? Am I a criminal for wanting to live elsewhere? Or is it my muddy feet you fear will dirtify your white couches? I will clean them at the door.

“It has become like a criminal act for an African to openly admit planning to move to another country,” says Elnathan John. “We are made to swear we won’t stay. When a European or American wants to move to ‘Africa,’ they don’t apologize. They say it with pride.”

A few years back I went on a solo backpacking trip through South America. It took me around three to four months—and lots of embassy visits to obtain my visas for Brazil, Chile, and Argentina. Peru was part of my itinerary but I could not get hold of the embassy, however much I tried. I was assured by the other embassies I would be able to obtain a visa on arrival in Peru.

They were wrong.

As I was denied entry into my flight from São Paulo, Brazil to Lima, Peru everyone watching probably wondered what crime I had committed to be pulled aside like that. These are the indignities of having certain passports. I was rerouted to Bolivia, where I could get a visa on arrival. My Machu Picchu plans came to an end. Another injustice at the hands of the visa gods.

In Buenos Aires, the wonderful friends I had made from Germany, UK, and Australia one day suggested visiting Montevideo, Uruguay for the day. It’s only four hours away by boat. I told them I would not be able to join.

“Why? You need a visa for Uruguay? Can’t you just get it on arrival?”

“No my friend. I sometimes believe that Africans will need visas for heaven too.”

I was filled with self-pity as I saw myself through their pitying eyes. I was the poor relative from the village who comes to the big city and should be grateful just to be in the big house with my city relatives. When the city relatives come to my village, we slaughter a goat for them, line up the traditional dancers—they can stay forever—because we are humbled and honored to have them.

I have never had passport privilege—never imagined I could move to your country on a whim, become an expatriate with all the trapping it brings. I have never thought of flying to another country under the assumption I would figure out how to get in once I landed. I try to sympathize when I hear you complain about how difficult it is to get a work permit in my country.

At most airports, I feel inadequate pulling out my Kenyan passport. Even armed with visas, you are never safe. A visa will not ensure you entry into a country. You still have to deal with the surly immigration official who will suspiciously ask, “And what are you here to do?” You will turn into a babbling fool pulling out your envelope with accommodation reservations, letters from your employer, bank statements, photocopies of each and every document that proves you are you. Everyone else will brandish their US passports, UK passports, Swedish passports.

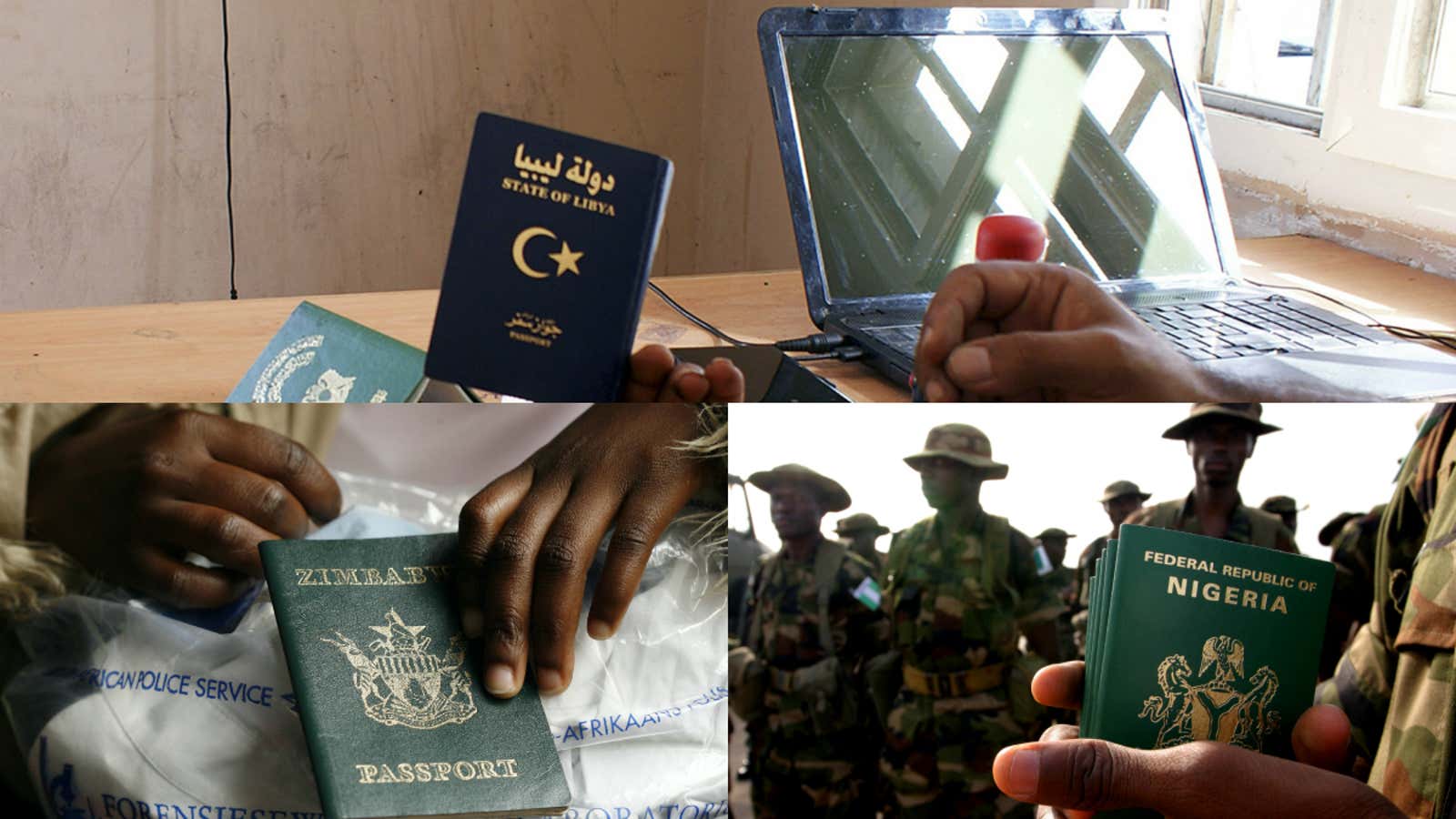

Sometimes you will see other Africans: my fellow Nigerians with their distinctive green passports, Congolese passports, sometimes the odd Somali passport or two, and several times those with no passports, but asylum papers or other travel documents that make you remember you are fortunate to have a passport. We will all give each other that knowing look, “Bon courage!” You will also have that Nigerian traveler with the thickest “Naija” accent who just in time pulls out a British passport and you feel a tinge of jealousy knowing he was one of those lucky ones whose mother gave birth to him in the UK when they still gave citizenship at birth. Lucky guy. It’s the same feeling when you are in a restaurant and everyone pulls out their iPhones then you pull out your Motorola T190. These African passports will shame you.

In that massive bedroom in Ataturk airport in Istanbul that I fondly named the Ebola Holding Pen, I overheard great conversations. The Congolese on their way to university in Russia. The Nigerian garment traders who were linking each other to “Uche” who will show you all the good Nigerian shops in Istanbul. I thought of the resilience of us passport undesirables. Here were people traveling on passports even less powerful than mine—doing business, going to far-flung cities close to Siberia for higher education, supporting local Nigerian businesses in Istanbul.

Immigration will not stop—many of these people have no intention of staying on in your country indefinitely. They are seeking better opportunities and will eventually move back home. They are trading. They are working. Some will stay. If they do, is that the end of the world? How many of you were born in the same country as your great-grandparents? Migration is natural. The birds do it. The bees do it. Humans do it.

President Obama called during the UN General Assembly meetings: “The existing path toward global integration requires a course correction. We need to work together to see the benefits of integration are more broadly shared.”

But I ask: “Is this integration meant to be a one-sided affair? Integration for the superpowers, free flow of labor for the wealthier countries, and acceptance of the status quo for the rest of us—the poor relatives?”

I say no.

The problem is I saw the world, and now I feel I have a right to it as much as everyone else does. But the little injustices keep reminding me to get back into my corner and stop trying to get into your borders. We have seen the world—and we want to be fully included in it—with dignity.