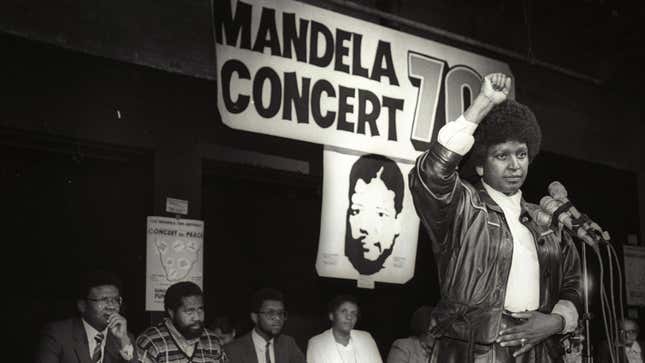

Even at 80, Winnie Madikizela-Mandela captures South Africa and the world’s imagination. Unlike the partners of other liberation struggle icons, Madikizela-Mandela has refused to live a quiet life in a free South Africa, courting controversy and making great personal sacrifices throughout her career as a political activist.

Born on Sept. 26 in 1936, in one of South Africa’s most scenic corners in the Eastern Cape, Madikizela-Mandela is today a globally recognized figure. Her life has been captured on television, in film and even opera, thanks in part to the reputation of her late husband Nelson Mandela, whose name she reportedly once described as a burden. When Mandela was first jailed, Madikizela-Mandela was indeed the young wife and mother who took up her husband’s fight. But by the time he was released, that fight for a non-racial South Africa was just as much her own.

Legend has it that Nelson Mandela felt he’d been hit by lightning the first time he spotted the young social worker in 1957. But soon after they married, Mandela was arrested again, tried a second time for treason, and sentenced to 27 years in prison.

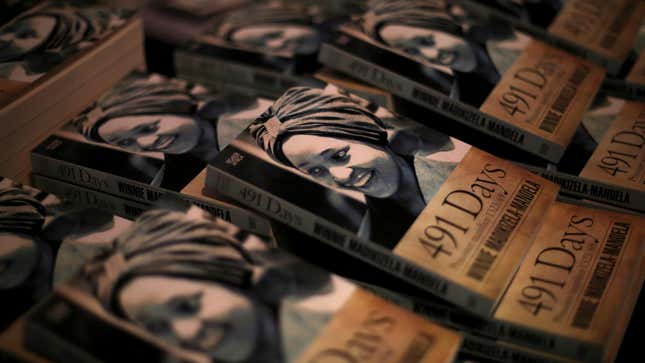

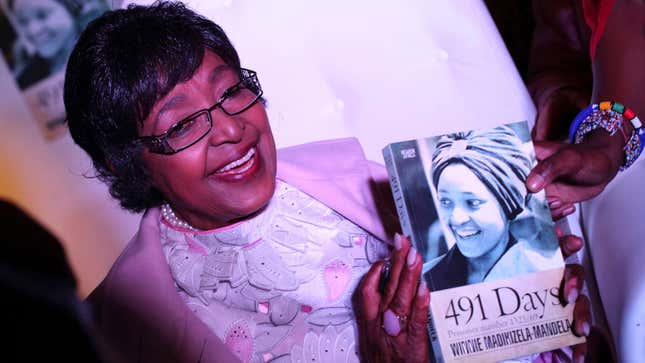

Throughout her husband’s incarceration, the young woman withstood police harassment and defied the apartheid government, continuing her political activism. She was detained under terrorism laws for 17 months in 1969. On her release, she continued to organize for racial equality, establishing groups like the Black Women’s Federation and the Black Parents’ Association during the 1976 youth uprising.

From 1977 to 1986, she was banned from her beloved Soweto. As soon as she returned home, she resumed duties in the African National Congress. The ANC was banned, but Madikizela-Mandela sheltered young activists and helped build an underground network of insurgents. She was known all over South Africa’s largest black township, and today her small home is a museum. She recently opened a restaurant nearby to take advantage of what is today a busy tourist destination.

Yet hers is not a biography that fits neatly into the narrative of a liberation hero. Many believe Madikizela-Mandela has blood on her hands, after a group of her loyalists beat a 14-year-old boy to death over rumors that he was an apartheid government spy in 1988. Years later, witnesses at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission claimed that Madikizela-Mandela had carried out the boy’s murder herself. She was eventually cleared when one of the men who were among her loyalists admitted to the murder. Those young men, under cover as a local football club, went on to commit twelve more murders.

During the 1980s, when South Africa’s black townships resembled a war zone, Madikizela-Mandela’s fiery rhetoric is also believed to have contributed to the phenomenon of necklacing—when suspected traitors were doused with petrol, trapped with a tire around their necks and bodies, and burned alive in the street.

Later, as a member of parliament, she was embroiled in scandal over mismanagement of public funds. At times, Mandela and the party distanced themselves from her, but Madikizela-Mandela continued to broad mass support.

After Mandela’s release from prison, the couple separated. After they divorced in 1996, Madikizela-Mandela became Mandela’s most outspoken critic. In an infamous 2010 interview with Nadira Naipul, wife of author V.S. Naipul, in the UK’s Evening Standard, Madikizela-Mandela accused the global peace icon of selling out South Africa’s liberation struggle.

“I am not alone. The people of Soweto are still with me. Look what they make him do. The great Mandela. He has no control or say any more,” she said. “They put that huge statue of him right in the middle of the most affluent ‘white’ area of Johannesburg. Not here where we spilled our blood and where it all started. Mandela is now a corporate foundation.”

Madikizela-Mandela later dismissed the interview as a fabrication. But Naipul stuck to her story and challenged Madikizela-Mandela to stick to hers.

Years later, she would be left out of Mandela’s will. She also recently lost her claim to his sprawling home at Qunu in the Eastern Cape. But her own home still sits on a hill in Soweto among her people. There she’s entertained political enemies, global dignitaries, and even MTV Base Africa. Among South Africans, she remains a complex figure that refuses to be quietly resigned to history.