One small-town German mayor thinks refugees can save the economy

Andreas Hollstein has been the mayor of Altena, Germany for a third of his life. In 1999, when he was first elected to run the small west-German city, he was 36 and Altena had roughly 22,000 people. Seventeen years later he’s 53, and there are less than 17,500.

Andreas Hollstein has been the mayor of Altena, Germany for a third of his life. In 1999, when he was first elected to run the small west-German city, he was 36 and Altena had roughly 22,000 people. Seventeen years later he’s 53, and there are less than 17,500.

With fewer constituents and a smaller tax base, Mayor Hollstein has had to get creative. Lacking funds to fix the potholes in the town center, Hollstein learned to pave roads and recruited citizens to help him set stone. To draw tourists, he organized an annual renaissance festival. It has become a top attraction in his home state of North Rhine-Westphalia.

Then last year, as Germany was grappling with an influx of 1.1 million migrants, the mayor raised his hand and requested an increase in the number of refugees that Altena was slated to resettle. When 284 migrants arrived, the town saw its first population uptick in a quarter century.

Now the question in everyone’s mind is: will these newcomers stay for good and save the town from dying? The short-term answer may be yes. A new integration law in Germany passed in the summer of 2016, gives states the authority to require migrants to remain in their assigned locations for up to three years. Germany’s population is projected to shrink (link in German) especially in rural areas and small towns like Altena. The new law may tip the scales in Hollstein’s favor.

Tensions surrounding the influx of migrants have been rising all over Germany. Since the migrant wave in 2015 there have been at least 272 assaults on migrant homes. Three incidents of violence committed by refugees have brought unrest to the German public and recently a Syrian refugee was arrested (Oct. 10) for allegedly helping to plan a terrorist attack. The tension has also been felt by migrants and residents in Altena; in 2015 an Altena firefighter caused national headlines when he set an apartment ablaze (link in German) to protest the arrival of the city’s new inhabitants.

Politicians in the center and on the right argue that the new law will ensure that migrants integrate and don’t end up clustering, or as SPD party chairman Sigmar Gabriel called it, forming “ghettos” (link in German). Dispersing migrants is also seen as better for assimilation and for more evenly distributing the burden of integration among the states. Each state has discretion over its resettlement locations. The country’s pro-asylum groups, however, fear that the new law isolates migrants from their communities, making integration harder.

What mayor Hollstein is facing in the town is perhaps at the heart of a challenge many shrinking towns in Germany are facing — it’s vital to make Altena into a place where migrants feel comfortable enough to put down roots.

Small town, big dreams

Altena has seen better days. The region was once known for producing knitting needles, an industry that has shrunken significantly. In 2008 the Nokia plant in Bochum, a 45-minute car ride from Altena, closed shop and 2,300 jobs disappeared. In recent years the city has had to shut down two elementary schools. The mayor is hopeful that migrants and their families can help bring those classrooms back to life: roughly 71% of all asylum applications in 2015 came from people under the age of 30, according to the Federal Office of Migrants and Refugees.

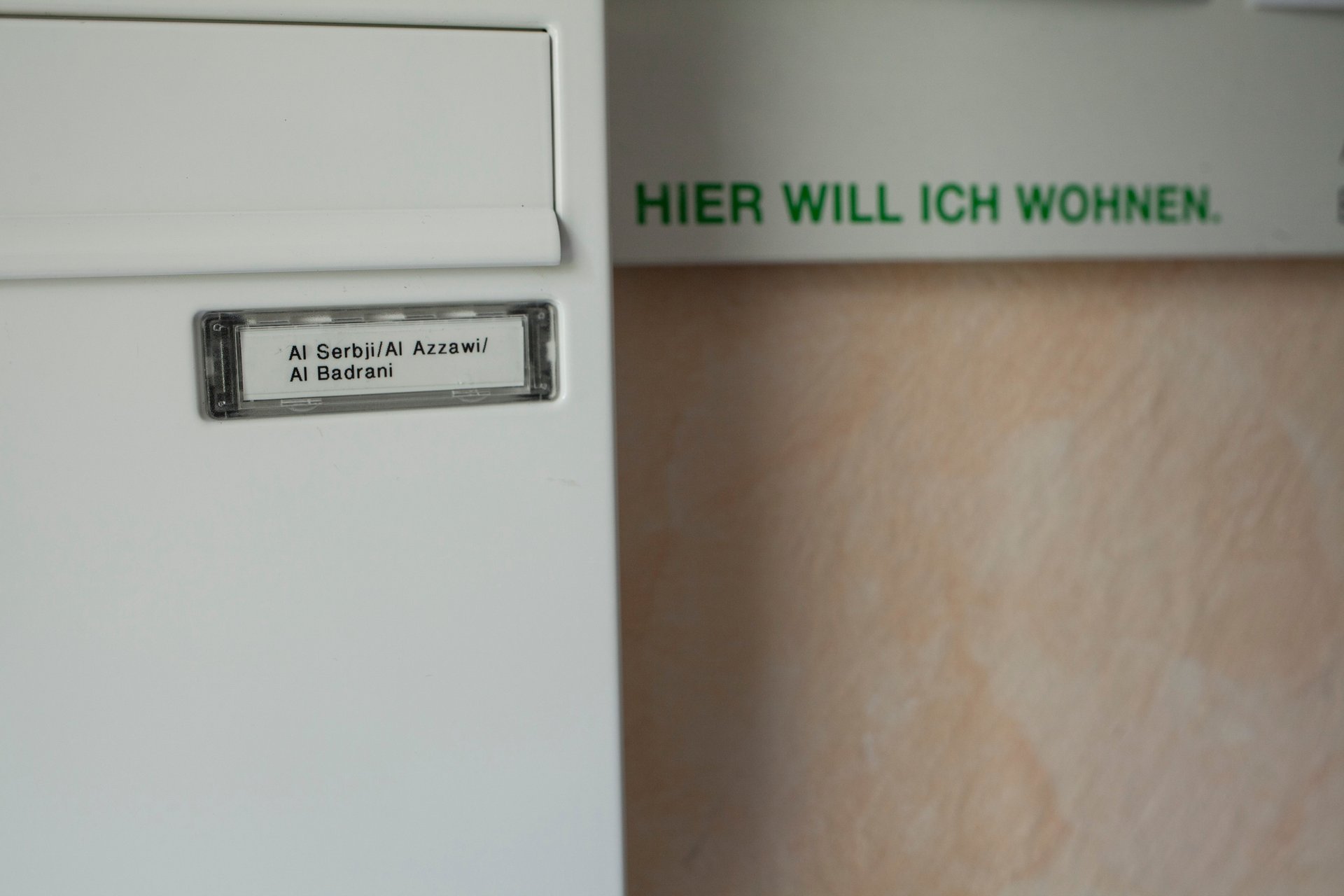

When Anas Alsrouji came to Altena, Germany, in 2015 he raised a lot of eyebrows in his neighborhood. His neighbor Helene Janowski, a 72-year-old retiree, had one particular issue with him. He didn’t properly sort his trash. Less than 12 months later when she comes home carrying groceries, Alsrouji lifts the heavy bags from her arms. Now she defends him when other neighbors complain about him and he calls her “großmutter” (grandma).

Alsrouji is just the kind of person a shrinking town like Altena needs. The 22-year-old student from Damascus, Syria, is young and dynamic and always trying to stay busy. He excels in his German classes and keeps fit by going to the gym multiple times a week. He constantly takes pictures with a camera that a volunteer loaned him

Unfortunately, Alsrouji plans to leave Altena. He’s grateful for all the support he has received but he did not think he would end up in this small a town. Altena is “boring” and lacks opportunities, he says. Within the next year or two he wants to return to a big city, be around other young people and go to university.

On paper, everyone benefits

Experts, like Reiner Braun, a board member at the German real-estate research institution Empirica Institut, argue that circumstances like the ones in Altena make small towns just the right place for migrants (pdf). A large number of Germany’s empty housing stock — roughly 1.7 million apartments — is located in smaller towns and situated in city centers or residential neighborhoods, rather than on the outskirts of growing and increasingly expensive cities. There are also jobs in these regions that require fewer language skills, according to Braun.

But what the city might be offering in room it lacks in the long-established support systems of cities with histories of immigration. Aladin El-Mafaalani, a professor at the University of Muenster who researches integration issues, said that there is not enough of an infrastructure in rural areas to support the influx of migrant populations and that building them out would be impractical and expensive. “In larger cities, migrants, whether they are refugees or not, can find a point of orientation from day one… a supermarket where someone speaks their language and someone who can explain how things work in Germany.” said El-Mafaalani. In rural areas, he points out, people can’t even begin to reorient themselves until someone comes to pick them up and teach them the ropes.

The good people of Altena

Volunteers like Nicole Möhling, 41, have gone out of their way to make up for this lack of infrastructure. Möhling remembers the first town hall meeting that mayor Hollstein put on before the arrival of the migrants. She was packing together welcome gifts for migrants —boxes stuffed with clothes, stationery, kitchen utensils and other things to start a new life.

“Those care boxes started everything,” she said. “Everyone felt that we could contribute.”

Some of Altena’s most successful programs have involved partnering locals with migrant households. Möhling was taking care of one family when she quickly became known as a person who could help. Everything from showing migrants the local supermarket to going to a doctor’s visit — Möhling has done.

Möhling has become a mother figure to many in the migrant community of Altena. She chats on social media daily with Marwa Al-Shahal, 35. They send snapshots of their coffee back-and-forth. She is helping another, Abdulhakim Bajbuoj, 30, with his paperwork and apartment search. Asrouji, the 22-year-old who helps grandma with her groceries, reads to her children and tries to help her with other migrants.

But even she understands that over time, this kind of commitment is not sustainable. “My children have become more independent and understanding,” she says when asked about the effects of her volunteering on her family, but she is starting to figure out how to say no.

Running low on patience

Not everyone in Altena welcomes new residents. Another local woman, who asked that her name be withheld, initially contributed to mayor Hollstein’s initiative when a migrant family moved into her building. She gave away old furniture, allowed them to use her kitchen and washed some of their clothes while they were waiting for a washer.

But over the course of several months, her patience ran out. Putting her toddler to bed became a struggle, she said. The family made a lot of noise — banging doors shut, letting kids ride what sounded like tricycles in the apartment, staying up and talking until way past midnight. Germans have legal protections (link in German) that entitle them to a certain level of quiet in their homes in the evening. The resident said she spoke to her neighbors repeatedly, exchanging friendly words and smiles, once bringing an Arabic speaker. But when she still wasn’t able to sleep, she contacted the authorities.

To her these disturbances signify a larger issue. “These people lived a different kind of life elsewhere for years. I don’t think they want to assimilate to the German way of life.”

It’s not just German citizens who feel the tension. Nesrin Abboud, 35, left her husband and two children in Damascus, Syria, last year to come to Germany and was hoping to bring them to her new home once her paperwork had been processed. She really liked Altena. Now she’s not sure whether she’d still be welcome and whether her husband would like the city or Germany altogether.

“I’m afraid they won’t accept my children. […] Maybe my husband won’t like it here. Maybe one day I will move from here.”

Reflecting back on the first year of his initiative to integrate migrants, Mayor Hollstein recognizes that it may have cost him some support. His office regularly receives calls from residents complaining about everything from noise levels to the separation of trash. A number of his constituents no longer greet him on the street. He has received anonymous death threats.

But Hollstein sees these issues as necessary evils to do the right thing. The grandson of a migrant who came to Germany from Lithuania, he has seen his family adjusting to a new country — not without trouble. He says he doesn’t govern by the mercurial nature of people’s opinions, but by what he thinks is right in the long-term. He believes that the voters will follow, and he has less than three years to find out.