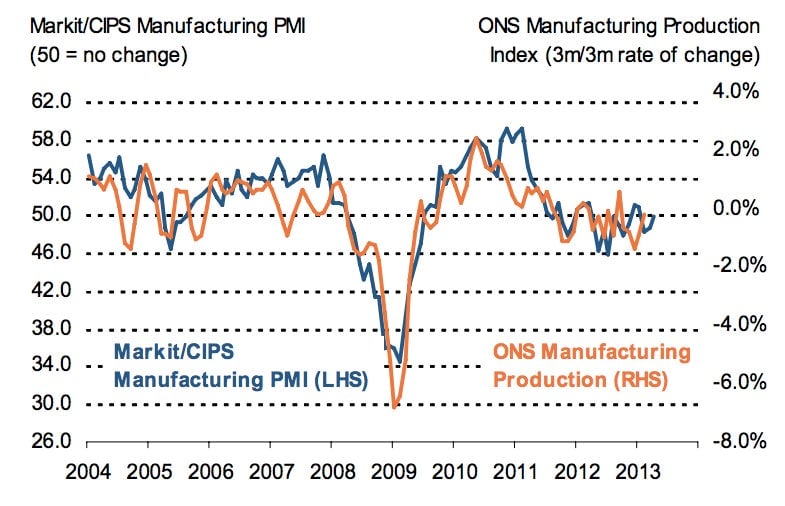

Purchasing managers data suggest the UK economy is stabilizing

UK purchasing managers’ index hints that the island nation’s economic fortunes are increasingly decoupled from those of the euro zone, where conditions continue to worsen. At 49.8, the UK’s April PMI indicates an ongoing decline in business activity (anything less than 50 represents a contraction in output; more than 50 shows an increase).

UK purchasing managers’ index hints that the island nation’s economic fortunes are increasingly decoupled from those of the euro zone, where conditions continue to worsen. At 49.8, the UK’s April PMI indicates an ongoing decline in business activity (anything less than 50 represents a contraction in output; more than 50 shows an increase).

But April’s data were higher than March’s 48.6, which implies that the pace of the output decline is slowing. And they’re just shy of signaling a return to growth. One read is that UK manufacturing is at last stabilizing, after having bottomed out in February. Here’s a look at the trend (pdf):

“Manufacturers report that the domestic market is just about holding its head above water, but was still a key cause of disappointingly weak demand, while a solid improvement in new export orders was the real surprise,” said Rob Dobson, senior economist at Markit, which collects and analyzes the data.

Export orders were “surprising” because they picked up for the first time in more than a year. That was mainly due to sales to North America, the Middle East, Latin America and Australia, offsetting the ongoing deterioration of demand from the euro zone, the UK’s biggest export market.

This is good news for the UK because orders tend to be leading indicators of economic activity, indicating how businesses are planning for user-end demand to shape up. It implies that UK manufacturing could start growing again in coming months.

April’s improving PMI data comes after the UK announced a slight but unexpected pickup in economic growth in the first quarter, with GDP expanded 0.3%. Manufacturing, which makes up a little more than one-tenth of the UK economy, had been something of a drag on the economy throughout the first three months of the year, offset largely by a revival in service-sector activity. Today’s signs of a stabilizing manufacturing sector hint that economic activity in Q2 could prove even stronger.

One more thing to note is that output costs, on balance, fell in April for the first time in eight months, largely due to falling energy and commodity prices. That tailing off of inflationary pressure “provides head-room for the Bank of England’s MPC to extend its accommodative policy stance if GDP growth fails to gain traction in the coming months,” said Markit’s Dobson.