The online Chinese-Kiswahili dictionary, Siwaxili, is full of useful phrases translated into both languages. Some are general: “My car is broken. Can you help me?” or “I will pay you later.” Others are more literary: “I will tell you a story.” And some are oddly specific: “One is already married. The other is still quite young.”

Siwaxili, the transliteration for Kiswahili in Mandarin, is the first comprehensive online dictionary. Few other Chinese-Kiswahili dictionary exist. China’s ministry of education published a dictionary in 2013. Before that, the last version was in 1971. The Siwaxili online dictionary has about 14,000 dictionary entries, or lemmata, according to its creator, Yuning Shen, a lexicographer studying African linguistics at the University of Hamburg where he is finishing a master’s degree. He has been working on the project from Germany, Tanzania, and Kenya since 2012.

“I get the feeling that more and more Chinese share the same view with Nelson Mandela—’If you talk to a man in a language he understands, that goes to his head. If you talk to him in his language, that goes to his heart,'” he says.

While living in Tanzania and Kenya, Shen noticed interest among his fellow Chinese in learning Kiswahili but a lack of teaching material and teachers with experience teaching Mandarin speakers. Tanzania and Kenya, where Kiswahili is a national language, are both home to growing Chinese communities as more Chinese companies win bids to build infrastructure projects and Chinese entrepreneurs and traders come seeking new business opportunities.

The dictionary is meant to cover the gamut of words and phrases that Chinese and Kiswahili speakers might use in China or in eastern and central Africa. Since releasing an initial version online in 2014, Shen has been updating it every month with new words and phrases gleaned from newspapers, literature, his own interactions with Kiswahili speakers, and most recently searches made on the Siwaxili site. Later this year, he is releasing a Siwaxili app.

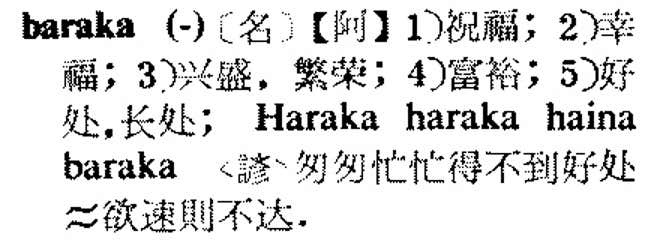

Proverbs were the most difficult to translate, according to Shen. The Kiswahili saying, Lisilokuwapo moyoni, halipo machoni, literally, “What is not in the heart is not in the eyes,” to mean that one does not care for those they don’t love, takes on a slightly different explanation in Chinese. The proverb in Mandarin (心里没有的东西,眼里也看不见) translates as, ”Your eyes cannot see what is not in your heart.” Others, like Haraka haraka haina baraka, or “Hurry hurry has no blessing” already had a Chinese equivalent—欲速则不达 or, haste makes waste.

As Chinese presence in Africa has grown, more schools have begun offering Mandarin and Chinese government-sponsored Confucius institutes have expanded to 60 locations on the continent as of last year. But fewer resources have been put toward training Chinese in local languages like Kiswahili, spoken by as many as 100 million people on the continent.

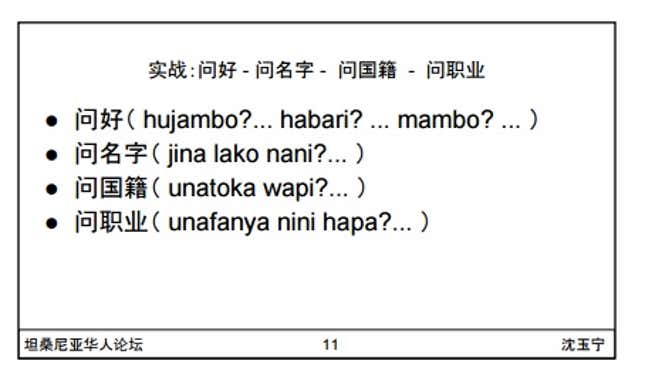

Shen believes it’s a business opportunity that deserves more focus. Using his experience building the dictionary, he also offers Kiswahili lessons through the messaging app WeChat to Chinese speakers in Africa. So far, about 500 people have joined his Kiswahili learning groups and about 600 users are using the online dictionary. The siwaxili website is free, but he plans to sell the app version of it for $30.

Some progress is being made. Last year, the Kenyan bureau of China Radio International, an English-language state affiliated broadcaster, began holding Kiswahili classes for Mandarin speakers in Nairobi. This year, a book of Chinese poetry was translated into Kiswahili for the first time.

It’s not just business opportunity that motivates Shen. He believes the continent suffers from a form of linguistic inequality, where local languages aren’t prioritized. ”Language is a powerful tool that mobilizes or immobilizes people,” he says. “I wish that African leaders will also promote their own languages in the future.”