A state of emergency has gone into effect in Ethiopia as the ruling party attempts to put down the biggest display of anti-government sentiment it has faced since taking power 25 years ago.

Roads in and out of the capital, Addis Ababa, have been blocked. Internet access is shaky and mobile data has been shut off, according to local activists. Under the decree, authorities will be able to search homes and detain suspects without prior authorization. Federal troops, who were only to enter regions like Oromia at the request of the local government, can now be deployed across the country.

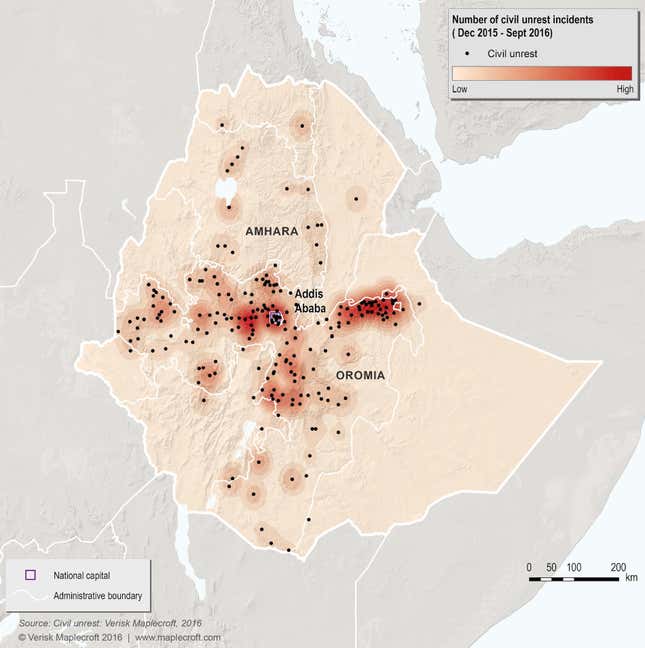

The Oromia region is home to the country’s largest ethnic group. Protests that started in the region last year have since spread across the country and now include members of Ethiopia’s second largest ethnic group, the Amhara. The Oromo and the Amhara are protesting the ruling Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front, dominated by a small ethnic group called the Tigray, for what they say have been decades of marginalization and violation of their rights and freedoms.

Curfews have not yet been issued, but a command post headed by the prime minister has been assembled to judge where and when they should be put in place ”should the need arise,“ Ethiopia’s attorney general Getachew Ambaye said on state-run television when the state of emergency was announced Oct. 9. Communicating, writing, and disseminating information that “could incite chaos” has also been banned.

“For the sake of maintaining public order the government believes that [the] temporary suspension of certain expression rights is warranted,” the country’s information minister Getachew Reda told the BBC.

That likely includes one of the anti-government movement’s most potent tools, the now famous protest gesture of raised arms, crossed at the wrist. It’s meant to symbolize being arrested by authorities.

“He did not specify the protest gesture in his words, but I am sure he is referring to the popular protest gesture. Plus, he said all kinds of communications might be banned,” Endalkachew Hilemiakel Chala, a doctoral student at the University of Oregon’s School of Journalism, from Ethiopia, told Quartz.

The government said failure to observe these new measures could result in five-year imprisonment. The state of emergency has been issued for six months, the maximum length allowed according to the country’s constitution. It can be renewed.

Ethiopia’s heavy-handed response to the protests has incited more protests. A protest last weekend turned into a stampede when security fired tear gas onto the crowd. At least 55 people died from drowning in the nearby lake or were crushed to death. In the week that followed, protesters burned cars, and destroyed businesses and government properties.

Communications have been cut off periodically over the last few months in attempt to prevent protesters from mobilizing. Human Rights Watch estimates that 500 people have been killed in the violence since last November, a figure that the government says is exaggerated.

After declaring a state of emergency, government representatives blamed the chaos on outside forces and “organized gangs” whose intent is to dismantle the Ethiopian state entirely.

“There are countries which are directly involved in arming, financing and training these elements,” Reda told a news conference today (Oct 10), naming Egypt and Eritrea, which are both involved in border disputes with Ethiopia.