The golden age of opening credits: Westworld’s eerie title sequence is a meticulously crafted short film

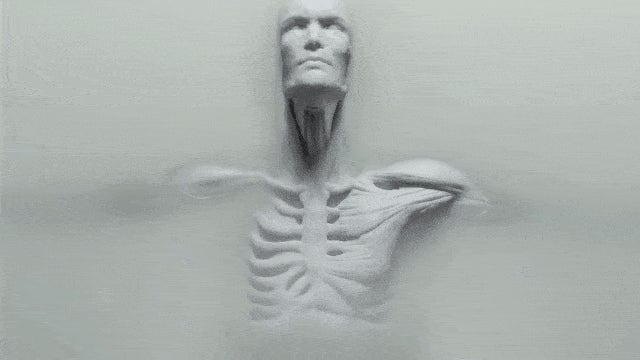

A blazing sun rises over the sierra of the American West—or is it an industrial lamp shining across the rib cage of an android skeleton? In Westworld‘s unsettling opening credits, it’s hard to tell. And that’s the point.

A blazing sun rises over the sierra of the American West—or is it an industrial lamp shining across the rib cage of an android skeleton? In Westworld‘s unsettling opening credits, it’s hard to tell. And that’s the point.

This polysemous image, the first of many in the HBO show’s title sequence, welcomes you to a world in which things feel very much out of place.

The show, about a Western theme park populated with humanlike robots, unnerves as much as it excites. The nearly two-minute intro sequence escorts viewers through the creation of one of these androids, from the 3D-printing of its bones, delicate tendons, and muscles until the final touch, when it’s submerged in a milky substance, ready to be dressed like a cowboy.

If that sounds like a lot to squeeze into the opening credits of a TV show, well, it is. But that, too, is the point.

Title sequences have come a long way from the days of sitcoms like Family Matters, when actors would appear doing some prototypical activity (playing with a dollhouse, waxing a car) and stop what they were doing, look at the camera, and greet the audience with a smile and a wink.

Today, opening credits are sophisticated, meticulously crafted short films, and people like Patrick Clair, the director of Westworld‘s opening sequence, are ushering the form into its own golden age.

“When HBO started to really stake its claim as being the benchmark for high quality drama in the late 1990s, they made a point of making one of the hallmarks of that really ambitious, epic main titles sequences,” Clair told Quartz. “That started the tradition of saying, if you want your shows to be among the best in the canon of television, then you’re going to have a really great main title.”

Prestigious shows with short and sweet credits, like Breaking Bad and Lost, might take issue with the notion that an elaborate main title sequence is a prerequisite for greatness. But name any “prestige” TV show of the last decade or so—The Sopranos, Mad Men, Game of Thrones, Narcos, The Americans, Dexter, House of Cards, Homeland, Orange is the New Black, True Detective, need I go on?—and there’s a good chance it features some flashy opening credits. (Art of the Title is a great site to reference.)

Clair knows something about the True Detective opening credits, since he made them too (for both seasons of the show, winning an Emmy for the first). He also worked on Netflix’s Daredevil and Luke Cage; Amazon’s The Man in the High Castle (another Emmy win); and AMC’s The Night Manager. His colleagues at Elastic, one of the industry’s premier studios, have made the titles for Game of Thrones and The Leftovers, among many of television’s best shows.

Normally, Clair and his team are brought in by a TV network after a show has finished filming to pitch one or multiple opening credits concepts. If they’re lucky, they’ll get hired and quickly start collaborating with the show’s producers.

“The biggest factor in a successful main title is how much you get a chance to work with the people who are at the heart of the process,” Clair said. In the case of Westworld, he worked closely with the show’s creators, Jonathan Nolan and his wife Lisa Joy, on developing the intricate sequence you see every week before an episode starts.

Clair’s team for Westworld included roughly six designers (led by Paul Kim), five modelers (who build all the individual elements—the horse, the robotic arms, the piano—that later get animated), and then four animators who bring all the pieces to life at the very end of the process (a team led by frequent Clair-collaborator Raoul Marks). It’s a highly collaborative orchestra, and Clair is the conductor. ”It’s one of those creative processes where you never really understand how it works,” Clair said.

What he does understand, though, is that he wouldn’t be successful without TV executives willing to embrace the unknown: ”You can go into these rooms and pitch these people really dangerous ideas, and they’re hungry for them,” he said.

The idea he and HBO decided upon was to offer viewers a glimpse of the man, or rather the robots, behind the curtain. The opening sequence takes place in some darkened, amorphous operating theater, where tentacle-like robot arms manufacture the park’s androids. One of them is taught to play a piano, which in turns begins to play itself. It’s robots teaching robots teaching robots.

But what makes the sequence truly unnerving and provocative is how it takes enormously powerful symbols of the American West and strips them of their context.

The sequence’s most stirring moment, one that feels as cinematic as any actual scene of a television show, is when an android rider, atop a pale, mechanical horse, raises her six-shooter revolver, as if riding into the heat of a gun battle. This visual is aided by composer Ramin Djawadi’s tremendous score, which transitions from a Philip Glass-like piano ditty into a sweeping orchestral composition moments before.

It’s a scene we’ve watched in countless Westerns over the years, but we’ve never seen it in this strange, charcoal world, being assembled, guided, puppeteered.

It’s an arresting visual, calling to mind one of the Four Horsemen from the Book of Revelation. (“And I looked, and behold a pale horse, and his name that sat on him was Death, and Hell followed with him.”) Clair and his team studied images given to them by Nolan and Joy, as well as the vast collection of Western iconography that’s entertained audiences around the world for decades.

“There’s this treasure chest of cool shit, and we get to just pillage that for great poetic imagery,” Clair said. “That’s the most thrilling part of my job.”

Perhaps more important than any single image in the opening credits is the more general feeling it instills in its watchers as they prepare to enter Westworld. A good title sequence will reorient your thinking. It’s a bridge from one world to another.

And whether you realize it or not, that bridge is often built with color. Think of your favorite TV shows—what colors do you see in your head? For me, Mad Men is red and black, with splashes of yellow. Game of Thrones is golden brown. True Detective is gunmetal and green. It’s no coincidence that these are also the colors accentuated in their main title sequences.

“Colors are a very precise language,” Clair said. Indeed, research has shown that color and memory are closely related. In, say, 20 years time, you might not remember any specific images from the Westworld credits, but you’ll likely remember that it was black and white.

Clair and his team didn’t create the color palette of Westworld (that was the work of Nolan, Joy, and the individual directors and cinematographers who film the show), but they carefully picked which hues to bring forth in the credit sequence. They knew early on that they wanted to depict this sterile, industrial, almost alien place, and that couldn’t be done with vibrant colors. Still, Clair didn’t want to forget the stunning vermilion orange of the show’s Western setting, so he added some desert buttes and bluffs into the reflection of the androids’ lifeless eyes.

That kind of obscure detail might just seem ornamental, but it’s integral to the process of creating a title sequence that its makers recognize will be analyzed and investigated ad nauseam by the show’s fans on social media. ”Everything in there is intentional,” Clair said. “Sometimes people read things into it that aren’t there, but other times they miss clues that are there.”

And the fans indeed read into everything. A cursory look at the show’s popular Reddit page will reveal dozens of threads about the opening credits alone. It’s as much a part of Westworld as the episode that follows immediately after. It’s all part of the singular experience of TV-watching in the 21st century.

Clair has won two Emmys (for True Detective and Man in the High Castle) and was nominated for three others (The Night Manager, Daredevil, Halt and Catch Fire). In some cases, he’s been honored more than the people who actually make the shows.

The Emmy for best main title design is given out at the Creative Arts Emmys, held a week before the main event that’s broadcast on primetime television. If the form continues on its path of prominence, it could find itself honored on the bigger stage soon.

But Clair, like any filmmaker, would tell you that he doesn’t do what he does for the awards. Instead, he just wants his work to be seen.

Again, and again, and again.

“The greatest compliment you can get as a titles designer,” he said, “is someone saying, ‘I didn’t skip your titles.'”