The only way for young people in London to buy a house is to go deeper in debt for a long, long time

Young people in London already know their prospects of buying a place in the city are dim. The average price of a home in the capital is £489,000 ($601,000), which is roughly 14 times the average annual wage in the city. But don’t despair, there is still a way to get on the property ladder (aside from begging for money from Mum and Dad).

Young people in London already know their prospects of buying a place in the city are dim. The average price of a home in the capital is £489,000 ($601,000), which is roughly 14 times the average annual wage in the city. But don’t despair, there is still a way to get on the property ladder (aside from begging for money from Mum and Dad).

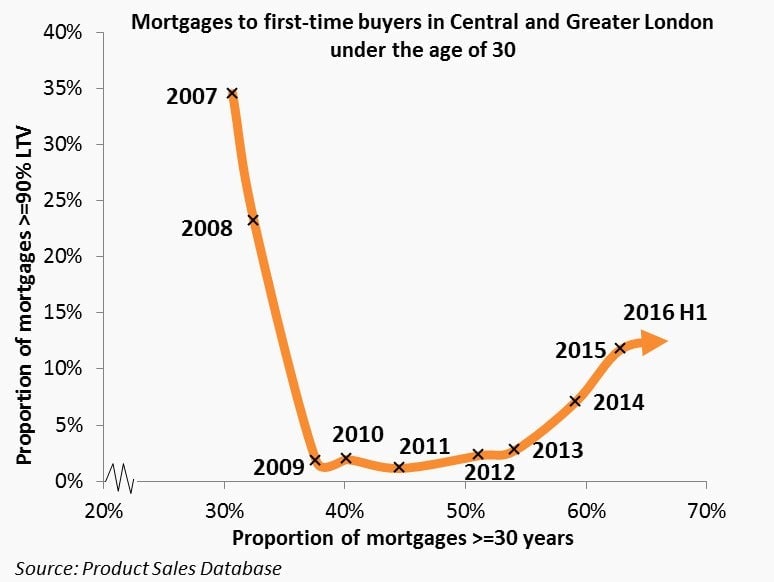

That way, it should come as no surprise, is to borrow heavily. But the financial crisis made banks wary of offering large mortgages with small deposits to young borrowers—in 2007, a third of mortgages were worth more than 90% of a home’s purchase price, versus around a tenth today, as Sachin Galaiya, a staff member at the Bank of England, explains in a blog post. Despite this, and government caps on the most aggressive types of home loans, high loan-to-value mortgages are making a comeback among young, first-time buyers in London.

The thing is, the only way people under 30 can afford loans that size is to pay them back over a very long time. The proportion of mortgages that are longer than 30 years has risen to about 65% this year, from around 30% a decade ago.

As Galaiya explains:

Consider someone with £2,000 a month available to spend on a mortgage. At an interest rate of 4.5%, they are able to afford a loan of £360k on a traditional 25-year repayment mortgage. However, by paying the same monthly amount over 35 years rather than 25 years, the person could borrow £63k more.

Once you get past the alarming suggestion that young people in London have £2,000 to spend on monthly mortgage payments, the prospect of voluntarily agreeing to decades more of indebtedness is equally disconcerting. That said, in Sweden and Japan 100-year mortgages are common, Galaiya notes. This is true, but Swedish mortgages work in quirky ways that limit monthly payments and, what’s more, the government trying to get borrowers to reduce the length of their loans amid concerns about soaring private debt levels. And in both Sweden and Japan, interest rates are substantially lower than in the UK.