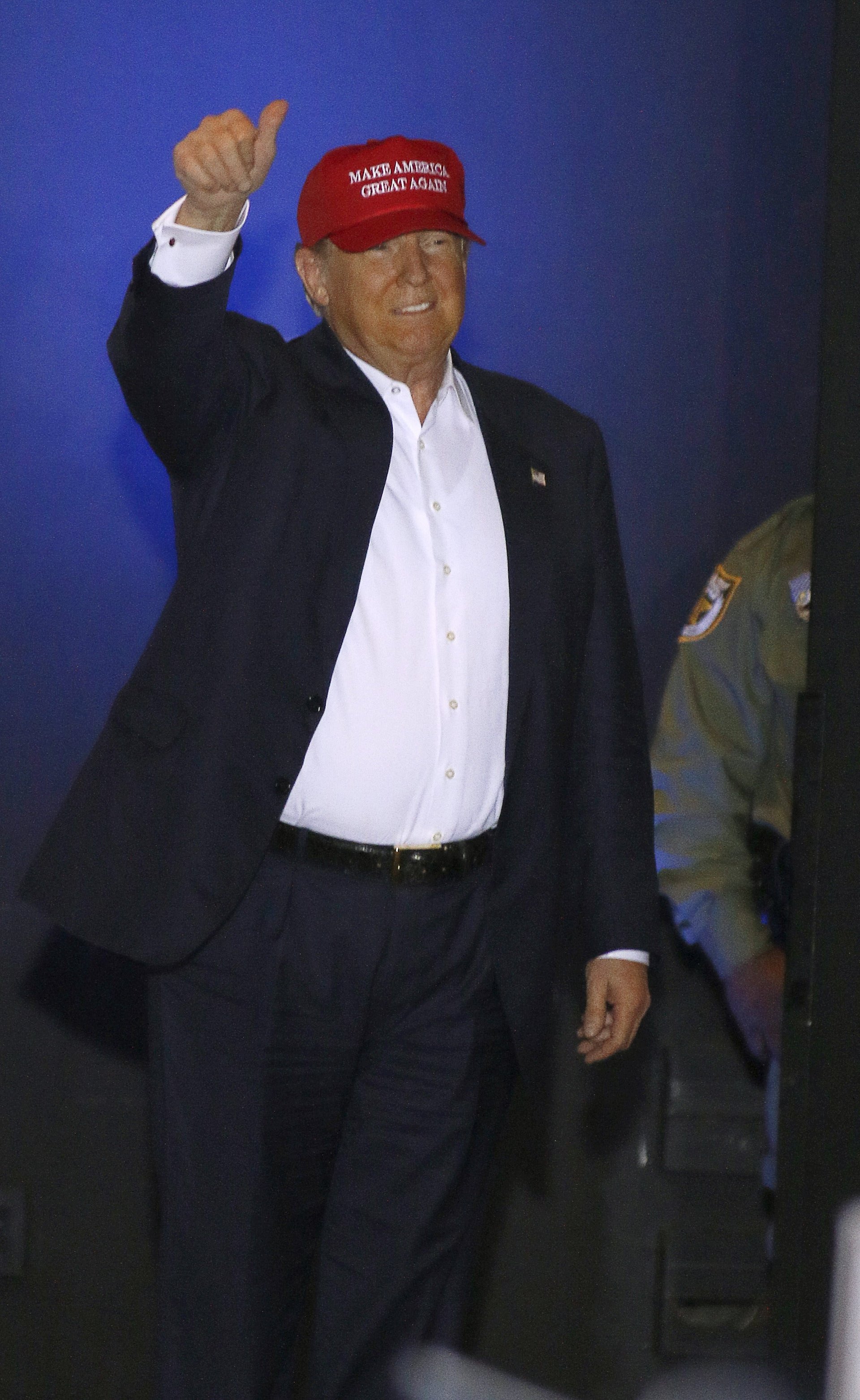

You will never see the “populist” Donald Trump in jeans or a t-shirt

When Ronald Reagan died in 2004, Newsweek, Time, and People magazines all ran the same photo of the former US president on their covers. Shot in the 1970s by photographer Michael Evans, it depicted Reagan, grinning and tan, in a cowboy hat and denim shirt. The image captured the core of his folksy, populist appeal and became a key component of his successful 1980 campaign for the presidency.

When Ronald Reagan died in 2004, Newsweek, Time, and People magazines all ran the same photo of the former US president on their covers. Shot in the 1970s by photographer Michael Evans, it depicted Reagan, grinning and tan, in a cowboy hat and denim shirt. The image captured the core of his folksy, populist appeal and became a key component of his successful 1980 campaign for the presidency.

Since Reagan, it has become standard for politicians to wear casual clothing to project an image that connects them to so-called “average American voters”—which generally means the white working class. Candidates make appearances in jeans, denim shirts or jackets, or they roll up their sleeves to remind people they understand their values and lifestyle in addition to their political views.

But this is one of the many ways that Republican nominee Donald Trump, who has been called the “perfect populist,” is not your typical candidate. For decades, he has made his public appearances almost exclusively wearing a suit.

He’s not the guy in jeans you get a beer with, and he doesn’t pretend to be. He’s the guy you see sitting at the bar of an expensive restaurant drinking an $18 martini. His suits—ill-fitting though they may be, as various commentators have pointed out—are quite often Brioni, a brand known for its luxurious and expensive formalwear. Its two-pieces can easily top $6,000. For more than a year he was reportedly not photographed without a jacket.

“You’ll never just see him in a t-shirt and jeans, he’s going to be in a suit,” his longtime butler, Anthony Senecal, said in an interview earlier this year. He really only breaks from that uniform on the golf course.

Voters notice. When Trump appeared on the Today Show a year ago, one person asked, “Have you ever eaten at McDonalds? Have you ever worn a pair of blue jeans? When was the last time you drove a car yourself?” (Yes, Trump has worn jeans before.)

It may seem a trivial point, but political image-making matters. “After WWII, with the advent of Hollywood, that sort of image becomes very important,” says Burton Peretti, a historian and author of The Leading Man: Hollywood and the Presidential Image. Think of Nixon walking on the beach in a full suit, and the generational disconnect that represented. Or Republican Lamar Alexander, who leaned heavily on his “man of the people” plaid, flannel shirt in his unsuccessful 1996 White House run.

Politicians now hire stylists and consultants to guide them on how they look. They know that in the era of 24-hour TV news and social media, people judge on appearance.

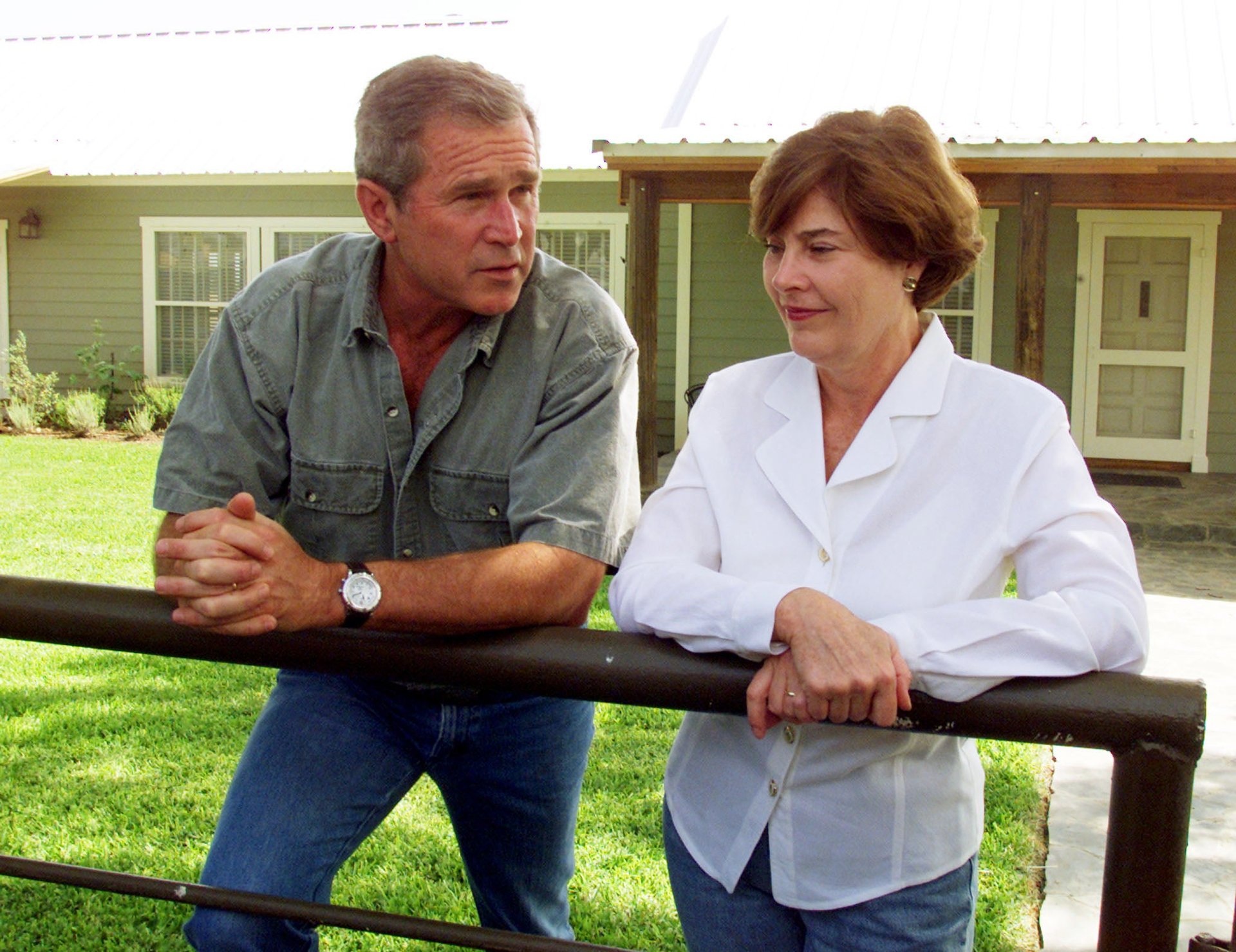

The narrative that developed to explain George W. Bush’s wins over Al Gore and John Kerry in the 2000s was that he was more likable, the regular guy “you’d want to have a beer with.” He was a baseball fan and a Texan who liked to be on the ranch. In 2012, buttoned-up Mitt Romney’s loss to Barack Obama was chalked up, in some part, to his deficient likability.

People may not be exactly voting for a candidate’s wardrobe. “But they do vote on two things that come across, contributed to by clothing,” says Lynne Marks of London Image Institute, a firm that trains image consultants who work with business people and politicians worldwide. “The first is likability and approachability, and the second is authority and credibility.”

In terms of their clothing, candidates often work to balance their authoritative and relatable images. They wear formal clothes such as a suit, or pantsuit, to project credibility, Marks says. They wear the casual clothes to signal that they’re likeable, regular guys, just like us.

Trump is entirely one-sided in this regard. Marks suspects he leans on his suited look to shore up his limited credibility when it comes to policy and governance.

Trump may be wise to stick with his business suits. Since the 1970s, when Reagan was sporting in his cowboy hat, Trump has been building his image as the New York City playboy in a suit. It may be a look frozen in another era, but it would seem inauthentic for him to abandon it now. (Trying to rebrand oneself visually has its own dangers, as Democratic presidential nominee Michael Dukakis learned riding around in a tank in 1988.)

And Peretti points out that Trump’s “Make America Great Again” hat, with its “rural connotation,” does visually connect Trump with working-class voters.

In any case, qualities such as authenticity and likability hardly seem to matter this election. Perhaps it’s because voters may not see much of either in Trump or his opponent, Democrat Hillary Clinton. But it may go deeper than that.

“His most die-hard supporters excuse so much about him… because they feel, ‘We need a revolution,'” Peretti says. “They’re excusing illegal behavior, and immoral behavior, and values—or lack of values—that they never would excuse in another candidate. So it’s understandable that they would excuse his Italian suits, too.”

Trump may not be good at making himself relatable to the average voter. But he’s adept at stoking their rage. He can do that just as well in a suit as in jeans.