The coming fast-fashion boom in the developing world spells big trouble for the environment

A boom in cheap fashion is coming.

A boom in cheap fashion is coming.

And unless we change the way we produce and sell clothes, it’s going to put massive strain on the environment and the people who make them. The conclusion comes from new research by McKinsey & Co., which looked at the way we currently consume fashion as well as the amplifying effect emerging markets could have as their growing middle classes buy more clothes.

McKinsey found that a culture of disposable fashion is proliferating in which retailers keep putting out greater volumes of inexpensive clothing. Consumers, attracted by the low cost and constant newness, are buying these clothes in greater quantities, and often wearing them only a handful of times before discarding them. This fast-fashion ecosystem uses large amounts of natural resources while producing carbon emissions that fuel climate change. It has also been linked to numerous cases of worker abuses in countries sewing the garments.

The report warns: “Without improvements in how clothing is made, these issues will grow proportionally as more clothes are produced.”

In all likelihood, more clothes will be produced. Between 2000 and 2014, clothing production worldwide doubled, according to McKinsey, and the average number of collections produced by European apparel companies in a year rose from two to five between 2000 and 2011.

This clothing boom is set to continue as growing middle classes in populous developing economies spend their rising incomes on clothes. ”In five large developing countries—Brazil, China, India, Mexico, and Russia—apparel sales grew eight times faster than in Canada, Germany, the United Kingdom, and the United States,” the report states. These consumers still buy a “fraction” of what shoppers in countries such as the US buy, but sales would still rise “significantly” if they continue buying more.

And it’s only getting easier to do that. Clothing prices aren’t keeping pace with other goods, meaning that, relatively speaking, clothes are getting cheaper. The number of garments the average consumer purchased each year rose by 60% between 2000 and 2014, McKinsey notes, and people are keeping clothing items for about half as long compared with 15 years ago, according to the report.

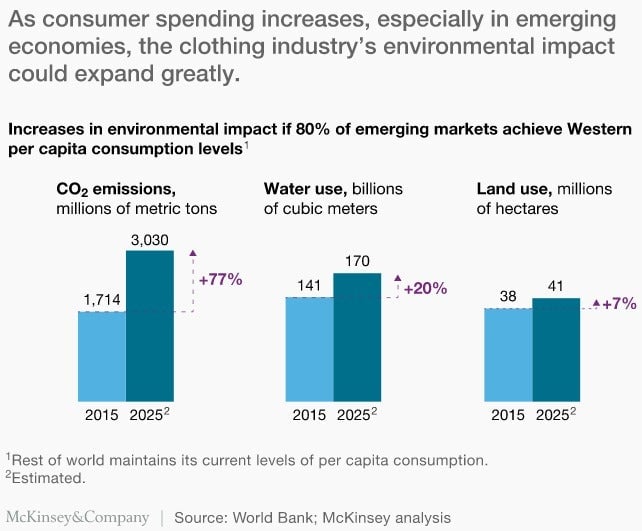

To make all this clothing requires land, water, and energy, and the impact doesn’t end in producing the clothes since water and energy are used each time a garment is laundered. If 80% of emerging markets rose to Western levels of per capita consumption, the effect on the natural resources we use alone would be significant.

What’s to be done? To offset this environmental impact “will likely require action across the industry,” McKinsey states.

It suggests, for one, that the apparel industry develop standards and practices for garments to be recycled. Currently, it’s extremely difficult to separate out fibers by type in fabrics made of blends, and mechanical methods of recycling cotton degrade its quality. McKinsey suggests more investment in chemical methods. (Textile technology company Evrnu and Levi’s recently created a pair of jeans from mostly post-consumer cotton waste using Evrnu’s chemical recycling method.)

It also recommends establishing higher labor and environmental standards, encouraging consumers to use low-impact methods to care for clothes, and investing in development of new fibers.

These are known problems, however. Organizations and individual brands are working on them, but their progress isn’t always straightforward. H&M, which positions itself as a leader in sustainable fast fashion, is investing in programs to reduce its impact while cranking out huge volumes of new clothes. Like Zara’s efforts, including its new sustainable collection, these actions do little to offset growing footprints. And these brands are hardly alone.

Clearly, something needs to change. Brands need to take responsibility, but so do consumers, or the cost of all that cheap clothing could be greater than we’re all able to afford.