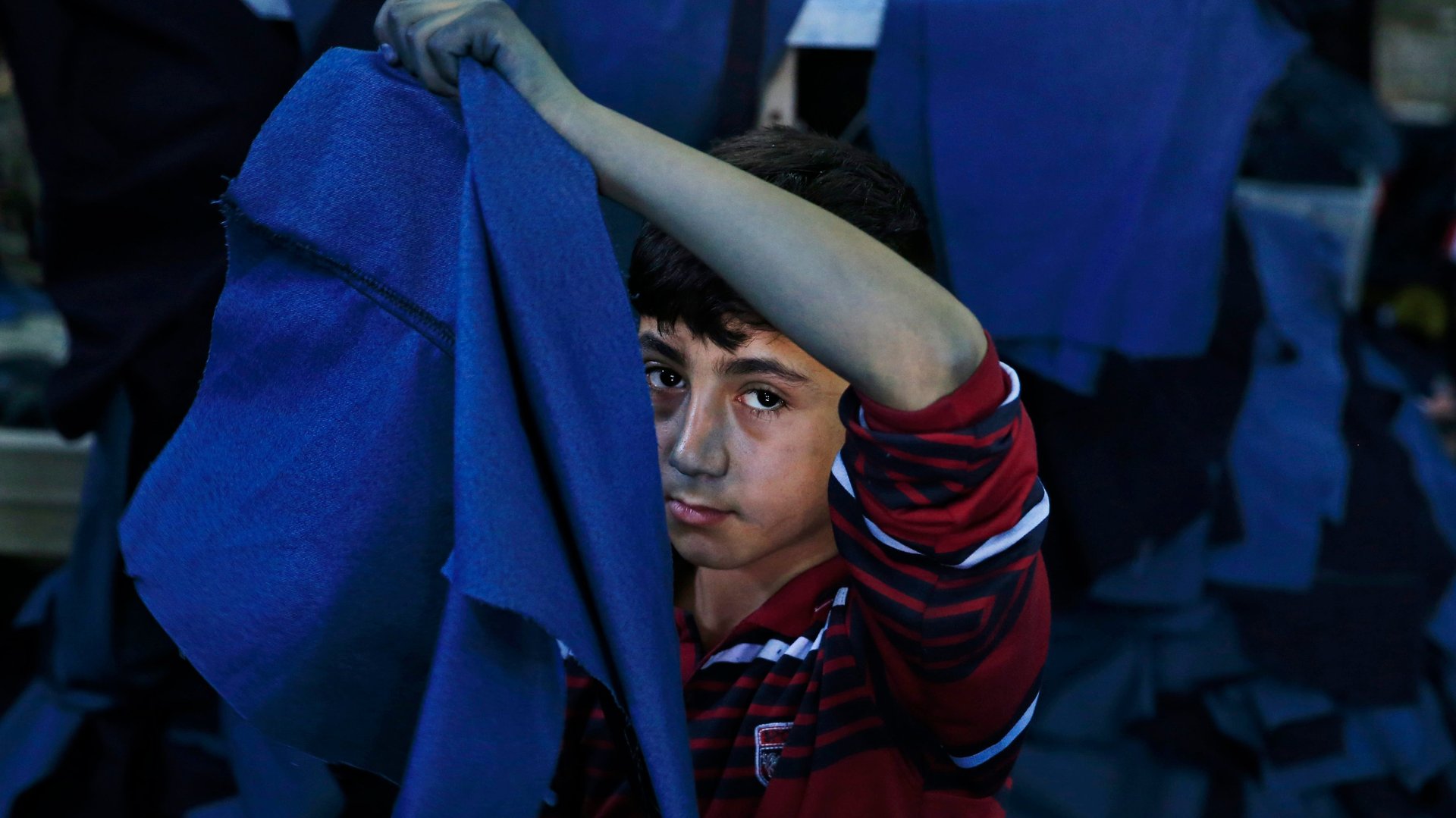

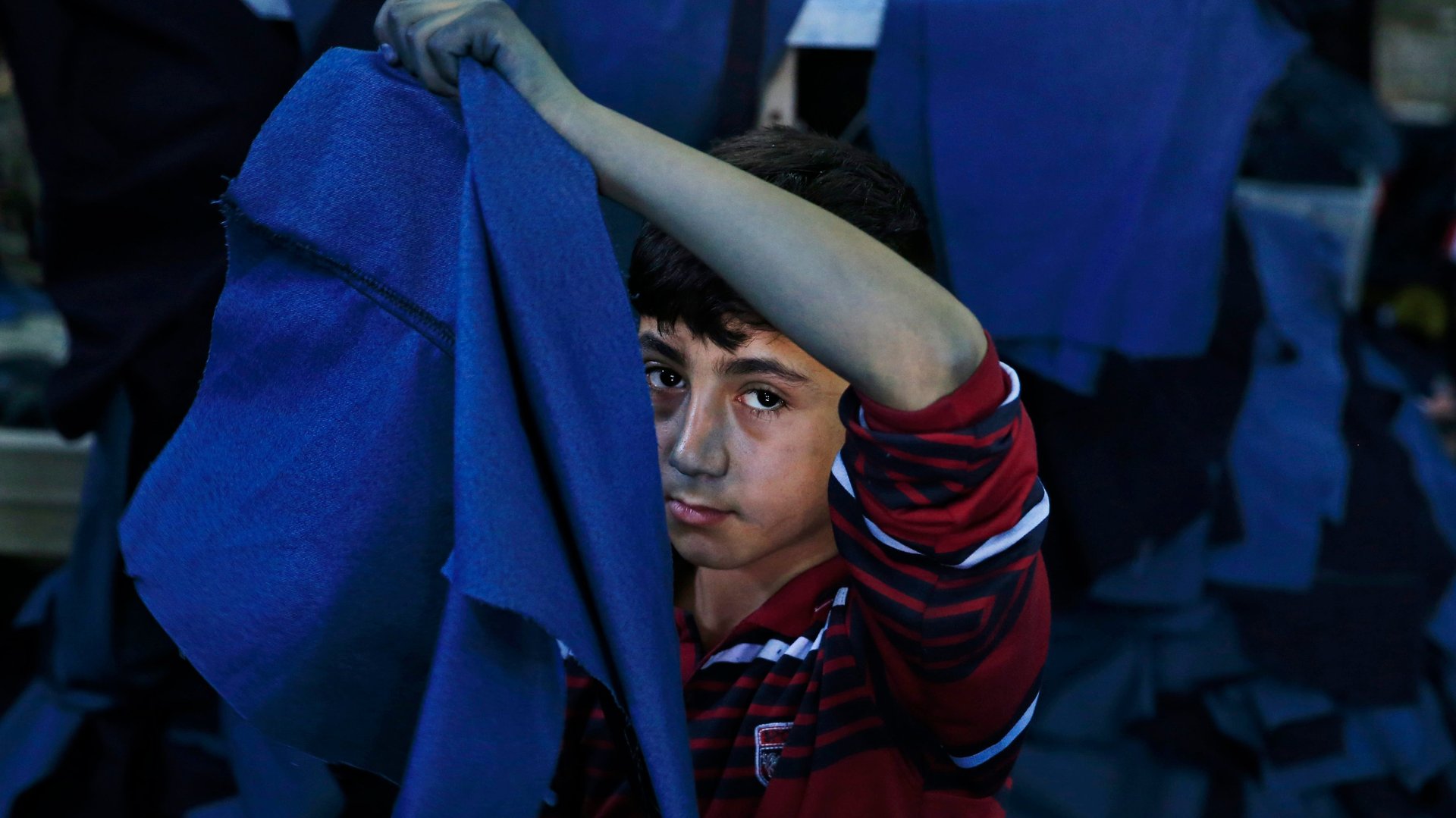

An investigation found Syrian child refugees in Turkey producing clothes for major brands

Nearly 5 million people have now fled the violence in Syria. More have gone to Turkey than any other country. Desperate for income, many have sought employment illegally in the country’s garment industry. As many foreign brands making garments in Turkey know, factories often exploit the availability of this cheap labor.

Nearly 5 million people have now fled the violence in Syria. More have gone to Turkey than any other country. Desperate for income, many have sought employment illegally in the country’s garment industry. As many foreign brands making garments in Turkey know, factories often exploit the availability of this cheap labor.

A report by BBC Panorama lends weight to critics who argue brands aren’t doing enough to safeguard against the practice. “Undercover: The Refugees Who Make Our Clothes,” scheduled to air tonight (Oct. 24) on BBC One, found Syrian child refugees in Turkey making clothing for popular British brands Marks and Spencer and Asos. It also found adult refugees working illegally at factories distressing jeans for Spanish brands Zara and Mango.

One of Marks and Spencer’s main contract factories employed seven Syrian refugees—despite the retailer’s claim that its investigations hadn’t any refugees in its supply chain in Turkey. The refugees often earned about £1 ($1.22) an hour, far below Turkey’s minimum wage, the BBC says, and the youngest worker the investigation uncovered was just 15 years old, “working more than 12 hours a day ironing clothes before they were shipped to the UK.”

The investigation also discovered a sample garment for Asos at a back-street workshop in Istanbul where several Syrian children were working. Asos told the BBC it was not an approved factory, but acknowledged that its clothes were being made there. “The company has since inspected and found 11 Syrian adults and three Syrian children under 16 at work,” the BBC reports.

Both companies say they monitor their supply chains and do not permit their suppliers to exploit refugees or children. Marks and Spencer said the findings were ”unacceptable to M&S,” and it has offered permanent legal jobs to Syrians working in the factory. ”Ethical trading is fundamental to M&S,” the company said.

Asos, which is also fighting allegations that it was exploiting workers in a UK distribution center after a BuzzFeed investigation, says it will provide financial support to the children so they can go back to school. It will also continue to pay the adult refugees until they are able to find legal work. “We have implemented these remediation programmes despite the fact that this factory has nothing to do with Asos,” the company said.

Similarly, the BBC found refugees working 12-hour days in one factory bleaching jeans for Mango and Zara. They worked without face masks, despite exposure to hazardous chemicals. Mango said the factory was an unauthorized subcontractor, and that its own subsequent inspections found no refugee workers and “good conditions except for some personal safety measures.”

Zara’s parent company, Inditex, told the BBC that a June audit had turned up issues at one factory, which had until December to make changes. It said its factory inspections are “highly effective way of monitoring and improving conditions.”

As the BBC’s investigation demonstrated, it can be difficult for brands to know exactly what their suppliers are doing. Factories may subcontract work without a brand’s knowledge to meet tight deadlines, and Turkey’s proximity to Europe makes it convenient for fulfilling last-minute orders.

The fast-fashion formula of speed and low prices has created billionaires in the industry, while in Turkey many refugees are sewing clothes to survive.