Could this red flag have saved us from these massive bank failures?

With the perfect hindsight that people tend to have, lots of them now say that you could have seen the 2008 financial crisis coming, if only you had your eyes open. All the warning signs were there—house prices growing much faster than rents, a rise in delinquent mortgages, and so on. The trouble is, it’s one thing to know that a crisis could happen at some point in the future; it’s quite another to know when.

With the perfect hindsight that people tend to have, lots of them now say that you could have seen the 2008 financial crisis coming, if only you had your eyes open. All the warning signs were there—house prices growing much faster than rents, a rise in delinquent mortgages, and so on. The trouble is, it’s one thing to know that a crisis could happen at some point in the future; it’s quite another to know when.

One of the most widely-accepted signs economists look for that things are turning bad is called the “credit-to-GDP gap ratio”. Essentially, it compares how much debt people and companies have now with how much they have on average.

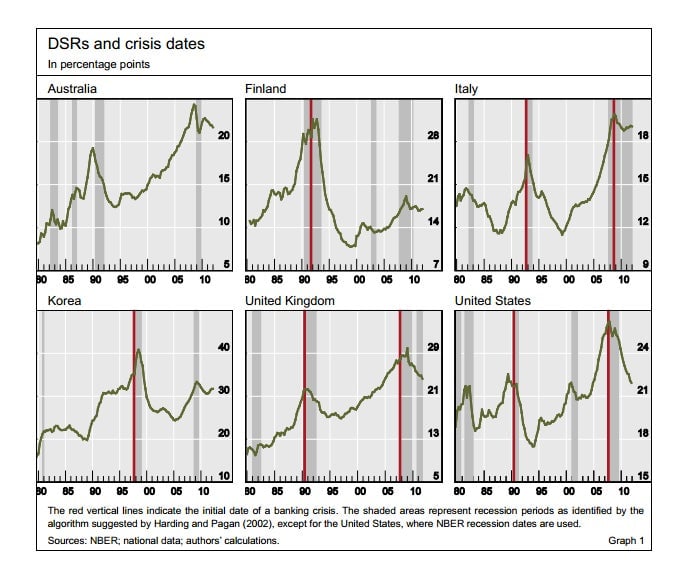

Now, researchers at the Bank for International Settlements—a kind of central bank for central banks—have found what they think is a better indicator. This is the debt service ratio (DSR), which is basically an estimate not of how much debt consumers and companies have, but how much they are spending in paying the debt off—again, as a share of their country’s GDP. Here’s how it would have behaved in the run-up to some of the most notable banking crises of the last decade or so.

“Most major peaks in the DSRs are associated with a crisis, suggesting that the ratio might serve as a reliable early warning indicator,” wrote BIS analysts in a September paper. “The DSRs’ peak levels are surprisingly similar across countries and time despite different levels of financial development. As a broad rule of thumb, the graph panels suggest that a DSR above 20–25% reliably signals the risk of a banking crisis.”

And compared with the credit-to-GDP gap, the researchers say, the DSR is better at warning that a crisis is about to happen. “While the credit-to-GDP gap starts to signal impending vulnerabilities well in advance of a crisis, a rapid rise in the DSR above 6% (relative to a 15-year average) is a very strong indication that a crisis may be imminent.”

Intuitively this makes sense, because GDP is like the national paycheck. If you have to pay more and more of your income dedicated to paying interest on loans, it leaves you less and less wiggle room if something goes wrong, like losing your job. If you have to declare bankruptcy, that means that the entities that lent you the money don’t get it all back. In isolated instances, that’s not a big deal for the banks. But if it happens to enough consumers and companies at once, look out below. On the other hand, trying to use GDP-related metric as a “real-time” indicator is notoriously tricky, as GDP is often revised significantly over time.