Zora Bikangaga was born in Fresno, California and grew up in a white suburb in the state’s north called Healdsburg. As one of the only two black boys in the neighborhood, Bikangaga was the subject of racial slurs and threats of physical bullying. He was called terms like porch monkey and a coon; a shopkeeper once asked him to empty his pockets to see if he was stealing; and a childhood friend once told him to sit in the back of the class “where you belong.”

Growing up in the 1990s, Bikangaga didn’t quickly grasp where the hatred and racism were coming from. The son of Ugandan immigrants, he took pride in the history of his family. His father was a cardiovascular surgeon, his mother studied public health and was a lactation consultant, and his grandfather was a regional monarch back in Uganda. The notion within the family was that they “were just as good as everybody else” in the city. Yet the attacks against him became more pronounced as he grew into adolescence, and Bikangaga, who eventually stretched out to a gangly 6 feet 6 inches (198 cm), understood that “I wasn’t the cute black kid anymore.”

But it wasn’t until he undertook a social experiment in college that Bikangaga clearly grasped the narrative about being black in America. The summer before he transferred to Westmont College in Santa Barbara, Bikangaga pretended to his future roommate that he was a Ugandan student and put on a thick accent. When he reported to school, he wore a colorful traditional shirt and sandals that he had bought in Uganda, and falsely impressed not only his roommate but his new friend’s family too.

“Immediately, they were so warm to me and so friendly,” Bikangaga recently told the weekly radio show, This American Life. “I had never had someone react to me in that way.”

Through his experiment, which started as a joke among friends, Bikangaga learned that there was a false narrative that placed a certain expectation of black people in America. As the son of black immigrants from Africa, he grew up with a feeling that he was different from African Americans who had lived in America for centuries, and who bore the burden of America’s racist and troubled past. But the experience of that first semester in Westmont taught him that the color of skin was a marker that he couldn’t evade.

“It’s confusing but now I can look back and see where the racism came from,” Bikangaga told Quartz. “There’s a narrative in this country that was meant to suppress black people or people of color. It’s the same narrative that was meant to suppress people during colonialism.” As Africans coming to America, he said it “is essential for us to understand that narrative and understand how we get put into that narrative and to call that out.”

The question of what it means to be black in America is something the children of the African immigrants have started to question and explore. African immigrants make up a small share of the US immigrant population, but a 2015 Pew Research analysis of US census data showed that their numbers have been doubling every decade since 1970. There’s also an upswing in the African diaspora, with research showing that they are increasingly affluent, educated and very successful.

Yet, money and position have not necessarily acted as a bridge into the fabric of American society. Bikangaga’s experience is similar to one recently narrated by Yaa Gyasi, the Ghanaian-American writer, and author of the bestselling book, Homegoing. Growing up in Huntsville, Alabama, Gyasi lived in a white neighborhood, and her father had a tenured job at the university. She performed in the school and church choir, tutored in French, started working at 15, bought a car by 17, had a grade point average of 4.2, and was accepted into every college she applied to, including Stanford.

Gyasi wrote that she did all this because as a lone black girl, “The city was the perfect place to put my goodness to test.” Yet, her plan didn’t work. She was still called a “nigger,” her colleagues wondered why she didn’t have an accent, and the neighbors called the police on her 12-year-old younger brother as he rode his bike in a nearby lot. “This is the same version of this too common story of black boys in America,” she wrote. “In the other version my brother dies.”

For Zora, following his bad experiences in high school, the accent gave him a sense of control over the way people perceived him. But later on, he found out that there was also a pitfall in his new funny character, “because there were people who were really condescending who assumed that I didn’t know anything or [were] not as educated as I was.”

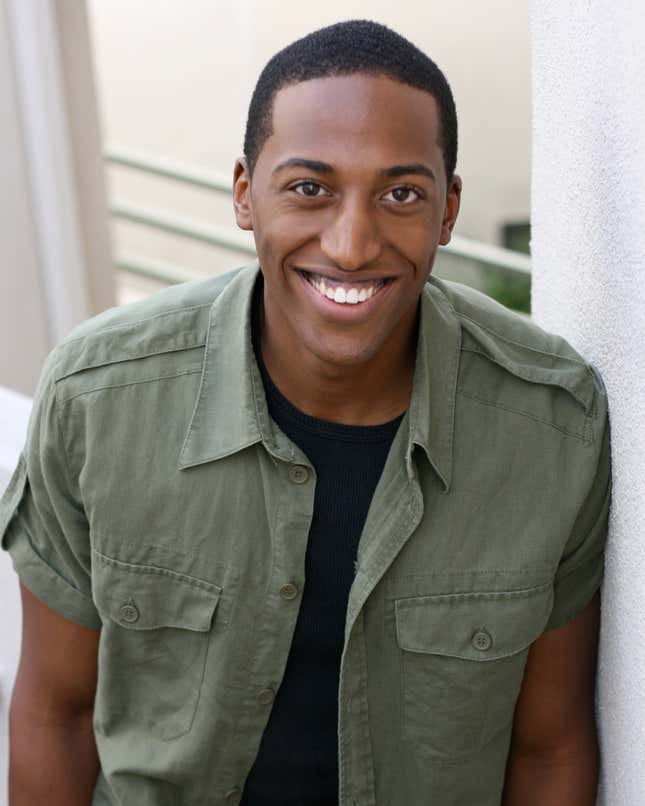

As a writer, actor, and producer now, who also doubles as a student and teacher of history, Zora says the experience gave him a deep sense of appreciation for what his parents went through when they first came to America. Despite his father’s education and position, he says, he has been treated with condescension many times.

The experience also gave him a perspective of who he was: a black man, the son of Ugandan immigrants, who proudly calls America home.

“I can be all of these things and understand that,” Bikangaga said. “I don’t need to fit into whatever idea people have of me just because of what I look like.”

Bikangaga finally revealed his background and origin to his friends in college–to their complete bewilderment. One of them, a young African American lady Zora was particularly fond of, told him: “Oh, you sound like a white boy!”