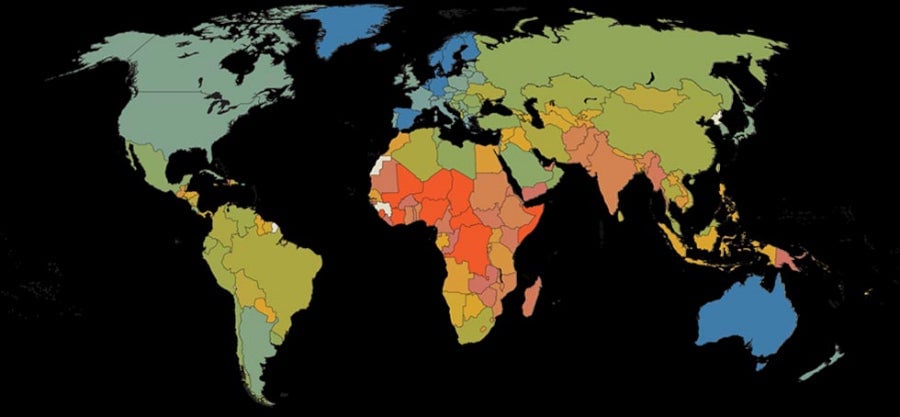

In one map, the best and worst countries for moms

This Mother’s Day, you might find the best-off äitis in Finland, and the worst-off mamans in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Those are the best and worst countries for moms, respectively, according to one international ranking released this week:

This Mother’s Day, you might find the best-off äitis in Finland, and the worst-off mamans in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Those are the best and worst countries for moms, respectively, according to one international ranking released this week:

The index, compiled from external data sources by the charity group Save the Children, is based on five metrics: the lifetime risk of maternal death, the under-five mortality rate, years of formal schooling, income per capita, and the participation of women in government.

To anyone who follows these things, the winners and losers are depressingly predictable. The top 10 are all in Europe (and Australia), bolstered by their widespread availability of maternal healthcare, and the bottom 10 are all in Central Africa. (Though to be fair, this is an index of quantifiable development statistics, not of happiness or contentment or even of having the most children—all of which could be construed to mean “good” motherhood and would likely shift some Global South countries to the top.)

Around the world, newborn deaths account for 43 percent of all deaths among children under age 5, and nearly all newborn and maternal deaths (98 and 99 percent, respectively) occur in developing countries where there’s a dearth of basic health care services.

The report is also a vivid reminder of how far the U.S. lags behind other industrialized nations on basic health indicators. Save the Children found that the first day of life is the most dangerous for newborns—especially when the mothers are poor and in bad health—and in the industrialized world, the U.S. has the most first-day deaths of any country (we rank 30th in overall mother and child well-being.) Save the Children attributes this phenomenon to too many preterm births, a high incidence of preteen pregnancy, and “poverty, racism, and stress.”

The organization also points to four products that could be lifesaving for newborns but can be hard to come by in the developing world: corticosteroids, which can help underdeveloped lungs mature, the antiseptic chlorhexidine for belly-button infections, antibiotics, and basic resuscitation devices. Their costs? At the lowest end, 51 cents, 21 cents, 13 cents, and 50 cents, in that order.

It’s not all bad news—the group also reports that the spread of community health workers has reduced infant mortality in far-flung communities in Tanzania and New Zealand, among other countries. Malawi’s newborn mortality rate has fallen by 44 percent since 1990, in part because of something called “kangaroo mother care,” in which mothers are encouraged to maintain constant skin-to-skin contact with their newborns in order to encourage bonding and help the infant produce its own body heat.

Still, the organization warns that the first day of life is the most dangerous for infants around the world. To bring down newborn-mortality rates in the U.S. specifically, the group recommended better maternal health care, more family planning, and better sex-ed for teens. (The U.S. has the highest adolescent birth rate of any industrialized country.)

“Helping babies survive the first day – and the first week – of life represents the greatest remaining challenge in reducing child mortality,” they wrote, and represents the biggest hurdle to meeting the Millennium Development Goal of reducing 1990-level child mortality rates by two-thirds by 2015.

Not quite a happy Mother’s Day report, but it’s an eye-opening one.

Olga Khazan is The Atlantic’s global editor.