Are the signals of journalistic quality different in our digital age?

Last week, we explored the absurdity of digital news economics, plagued by its absolute disregard for any notion of quality. An obvious question follows: For a piece of information, how do we define quality? How do we convert a subjective concept into numbers or metrics?

Last week, we explored the absurdity of digital news economics, plagued by its absolute disregard for any notion of quality. An obvious question follows: For a piece of information, how do we define quality? How do we convert a subjective concept into numbers or metrics?

The answer depends upon (a) defining relevant signals and, (b) making them machine-readable. The most advanced work in the field is found here in California, at the University of Santa Clara’s Trust Project. Sally Lehrman, her team and contributors have compiled a list of useful signals—read the report from the Trust Project Summit held in New York City last May (pdf here).

For my contribution, I will focus on three signal types that convey quality:

- Stated signals.

- Inferred signals.*

- Subjective signals.*

* To be treated in future Monday Notes.

Stated signals

Simply put, these are the signals that can be attached to any piece of news as a part of the production phase, right in the Content Management System. I actually addressed this topic eighteen months ago in this Monday Note.

At the time, I evoked a fictitious “Open Standard Quality Syntax,” a kind of lingua franca publishers and CMS developers could agree on. Needless to say, we are far from any significant progress in that direction.

The ironically-named Content Management Systems (CMS) make legions of malcontent users. Such systems are among the most frustrating pieces of software you can think of. I couldn’t name a single publisher happy with the one it bought or adapted. Everyone complains about the one they use, not without reasons. As an example, dragged down by its legacy print culture, and eager to milk captive clients, CMS provider Eidos Media added layer upon layer of pretend digital features aimed at giving an illusion of modernity for their obsolescent tool. It was promising enough to snare legacy publishers in an illusion of a upcoming modernity while still bogged down by an obsolete architecture.

In the meantime, digital native players such as Vox Media, Business Insider, the Huffington Post, or Buzzfeed wasted no time. They saw their CMS as a strategic weapon. To them, a modern CMS was much more than a tool to facilitate the newsroom’s workflow. Their CMS was the backbone of the entire revenue and marketing system, from analytics to audience profiling, ad serving, and social media management.

Why did these digital native medias act in such decisive manner? First, they were unencumbered by the past. Second, they were created (and funded) by tech-savvy people and true entrepreneurs, individuals whose culture understands that in order to make lots of money, you need to spend big.

By contrast, in the legacy media world—except for large outlets such as The New York Times or, more recently, The Washington Post—most incumbent players remained mired in their old systems, encouraged by a ruling class of techno-ignorant MBAs who didn’t grasp the strategic importance of modern tools.

Still, among news organizations that have built their own CMS, none has implemented the level of tagging required to convey the notion of a story’s quality. I see two motives for that shortcoming:

- Competition. Media don’t want such signals to filter out of their sausage factory and broadcast in the wild.

- The publishing world has no incentive to codify quality. Even if a media were willing to build such a system, today’s advertising community is woefully unable to deal with quality-related signals. A classic chicken and egg problem.

Despite this, I remain confident that the news industry will eventually deploy a robust quality-scoring system.

Furthermore, I bet the lead will come from large players such as Medium or even Google. Medium is actually best positioned to build a quality-scoring apparatus as it is both a public CMS, and has yet to find a model to monetize its vast content. In a likely application of the Pareto principle, Medium’s only way to make money is to monetize the 20% or so of its content to which a quality label can be affixed.

As for Google, we have rumors that it is working on a CMS aimed at small/medium size sites, and we know it controls both ends of the ecosystem, from production tools to advertising. In this case, both Google and the publishing industry have aligned interests in capitalizing on quality.

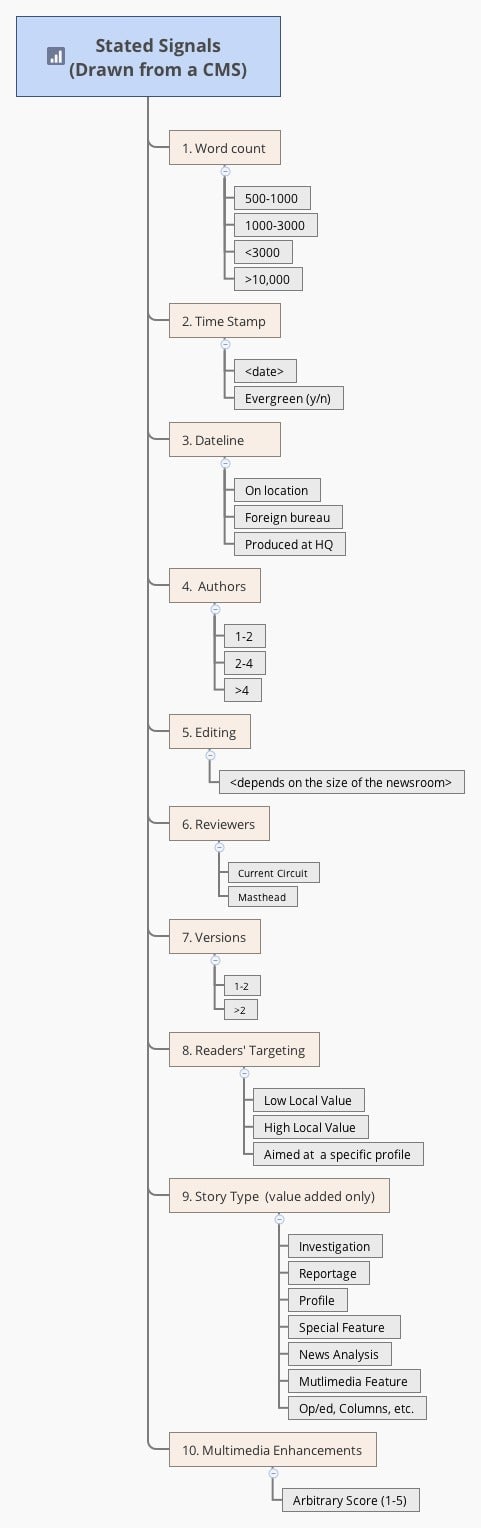

Coming back to stated signals, below is a tentative list of such pointers that could easily be compiled by a CMS.

Explanations are in order:

- Word count (#1): Long forms tends to score higher on quality than short pieces. Exceptions are many but, usually, a longer story requires a much broader scope of work than a short one. Therefore, signals such as Authors (#4), Editing (#5), and level of Reviewers (#6) are to be combined with the word count. That said, long stories can be terrible: some sites I’ll refrain from naming and that specialize in recycling others’ production do yield poorly aggregated work. Eventually, their Publication Quality score (see graphic at the end of this column) would be low.

- Time stamp (#2) is not as easy as it sounds. Many publishers tend to change time stamps even when they only make a minor update. This is because surveys show that freshness is seen as a key factor of audience appreciation. A key element is the “evergreenness” of a piece: some stories, because they are remarkably unique, and/or cover a topic in great depth, can keep a “must-read” status for a long time. In theory, it should be up to the top editors to decide if a piece deserves the evergreen label—keeping in mind that abusing the label will impact the Publication Quality score (#11).

- Dateline (#3) is a strong indicator for the uniqueness of a piece; it rewards the publisher’s investment in having reporters on location (a war zone as an example), or in maintaining a foreign bureau.

- Readers targeting (#8) is an important signal. It is part of the advertising machinery that sells specific profiles, such as “people in the market for a car,” or a geolocalized community.

- Story type (#9) is another finicky measure aimed at rewarding either exclusiveness, or a fuzzier notion such as the uniqueness of a story. As an example, an op-ed from Warren Buffett about the post-election stock market will carry a greater implicit value than an rote news analysis of the same “day after” topic.

- Multimedia enhancement (#10): That a story is supplemented by infographics or interactive dataviz can be considered a reliable indicator of quality.

A couple of remarks to conclude:

First of all, consider this as a work in progress. As I wrote earlier, this analysis is part of my journalism project at the John S. Knight Fellowship at Stanford University. It will evolve over time as I share these ideas with my Fellowship colleagues and with other sharp and restless minds that abound at Stanford and in the Bay Area.

Two, when taken separately, none of the ten indicators stated above can reliably convey a notion of quality. It is their combination that holds a hope of leading to a decent measure of editorial quality.

These signals are interdependent: each validates/corrects/confirms others in a checks and balances system.

In addition, this whole system is inconceivable without an independent third party that will verify that participants are not tampering with it. In order to be scalable, this has to be done automatically with an algorithm that will, among other tasks, verify the coherence of the set of signals, not merely in a point fashion, but over a period of time.

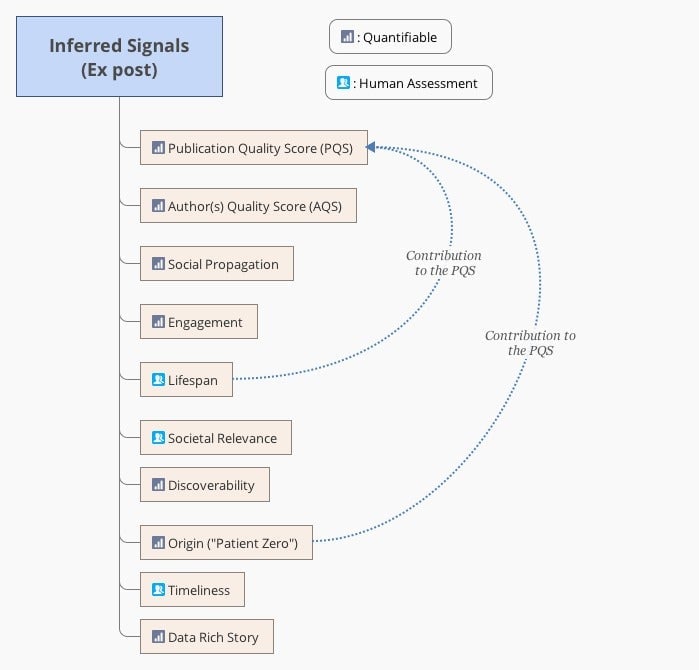

In a future Monday Note, I will address the question of “inferred signals”—the ones that can be deducted ex-post by third party platforms such as aggregators, search engines, or advertising services. Later, we’ll also discuss “subjective signals.”

As a teaser, here is a draft of the diagram for inferred signals:

…To be continued…