Nairobi’s colorful but chaotic local bus system is resisting being digitized

Commuting in Africa’s major cities is a daily hassle for millions of people where public transport systems are underdeveloped and typically overwhelmed by the fast-growing number of urban dwellers. For Nairobi’s colorful matatus, the local privately-owned buses which carry masses of people everyday across the city, the ubiquitous anarchy makes the hassle even more torturous for commuters. But from the anarchy and chaos, bus operators generate profits from an informal but vital system which they can adapt to suit their needs.

Commuting in Africa’s major cities is a daily hassle for millions of people where public transport systems are underdeveloped and typically overwhelmed by the fast-growing number of urban dwellers. For Nairobi’s colorful matatus, the local privately-owned buses which carry masses of people everyday across the city, the ubiquitous anarchy makes the hassle even more torturous for commuters. But from the anarchy and chaos, bus operators generate profits from an informal but vital system which they can adapt to suit their needs.

An estimated 70% of Nairobi’s four million residents rely on some 20,000 privately owned mini-buses as their main mode of transportation. Commuters in Nairobi often report being overcharged when it rains, at rush hour or whenever some roads are closed to motorists. On a normal day, passengers from the outskirts of Nairobi are charged an average of 50 cents (50 Kenya shillings) for a one-way ride to or from the city center. But, fares on some routes go up four or five times during these busy periods.

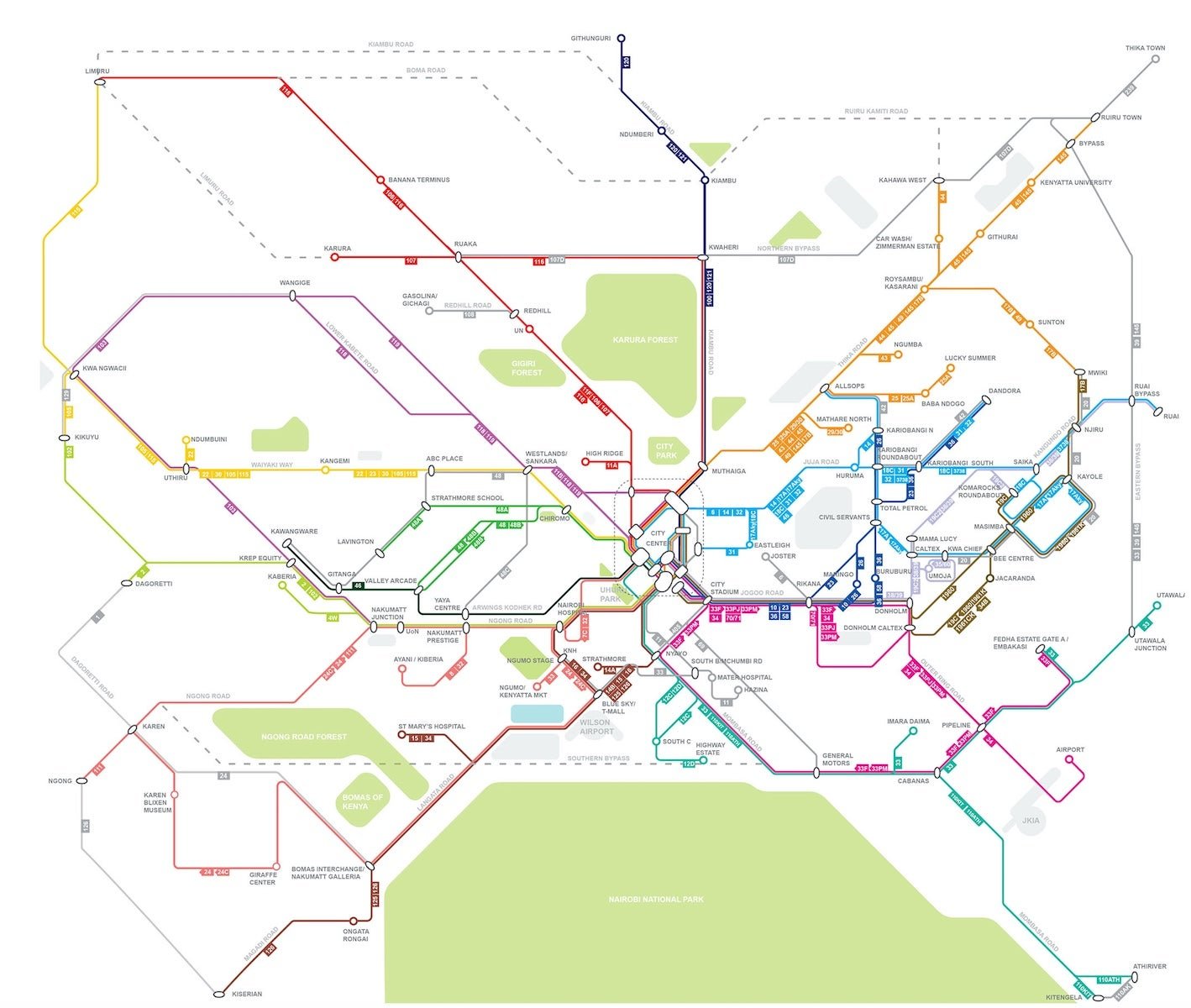

At the heart of such disorder, several initiatives have emerged to help with pre-booking tickets, guiding buses on designated routes and facilitating electronic payments. The Digital Matatus project, which released a map for matatu routes in Nairobi in 2014, sought to help commuters plot their routes on their smartphones. With this, riders could know the routes to use when moving around the city, save time and improve their lives. However, the cash intensive matatu industry is dependent on unreliable schedules to serve millions of commuters and has been resistant to attempts that would take away cash out of the operators’ hands.

“Once anyone makes payments electronically, there is more accountability in the system,” says Sarah Williams, director of the Civic Data Design Lab at MIT, which collaborated on developing the digital matatus project. But Williams says not all stakeholders want that accountability.

But, while technologies for cashless payments, mapping routes and for enabling pre-booking are raring to solve some of these challenges, Kenya’s matatu industry continues to defy such innovations.

“As in any project, there are a lot of challenges to overcome, but by being inclusive and transparent to all stakeholders in the work we are doing in Nairobi we have been able to gain support rather than opposition,” Williams says.

Digital Matatus itself acknowledges that some critical data needed for better analysis of the matatu sector does not exist. Some of the data has to do with service frequency and operating schedules. Fares are also inconsistent, while routes and bus-stops often change depending on traffic flow or patterns, police checks, commuter demands or the prevailing weather conditions.

Such is the fate that applications like the Magic Bus Ticketing, which has begun collaborating with Digital Matatus, will face once full implementation starts. Currently in the pilot phase on one of Nairobi’s transport route, Magic Bus Ticketing links commuters with bus drivers and enables them to book public bus tickets over their mobile phones. By aggregating demand along bus routes, it enables buses to go directly to where commuters are instead of waiting to get full.

The Matatu Owners Association chairman, Simon Kimutai believes technology will solve some of the critical challenges in the sector, but the resistance especially on the implementation of electronic payments is real.

“Our biggest problem normally revolves around chasing money. It is only technology that can digitize payments of fares and this of course will minimize cases of corruption in the sector,” he says.

Attempts to introduce digital payments, seen as one of the most progressive, came a cropper months after launch. The first attempt to introduce the electronic payments technologies was made in 2013 when Google paired up with Equity Bank to launch the now defunct BebaPay card. Google pulled the plug on the BebaPay cards in February last year, marking the death of the pioneer commuter card after it failed to pick up steam.

If such attempt was successful, it would have acted as an electronic ticketing system that would not only lead to greater accountability in the sector but also help owners to keep tabs on the revenues collected. It would also help the revenue authority to bring the industry estimated to generate about $2 billion in revenues a year into the tax bracket. The absence of a formal structure or system for tracking the revenues generated by the industry can partly be blamed on the industry’s failure to adopt the electronic payments technology. In Kigali, Rwanda, where the public transport sector is way smaller and less chaotic than Nairobi’s, electronic payments is already in use and is poised to succeed where Kenya has failed.