Chinese citizens are hijacking Xi Jinping’s latest propaganda tool

If the last sixty odd years of Chinese history were told through Chinese Communist Party slogans, this year would mark a turning point in who controls the narrative.

If the last sixty odd years of Chinese history were told through Chinese Communist Party slogans, this year would mark a turning point in who controls the narrative.

Elusive expressions like Jiang Zemin’s “three represents” (which refers to the three pillars of the party—military, culture and public interest) and Mao Zedong’s “destruction of the four olds” (which connotes the destruction of pre-communist Chinese values) catalogue important transitions in China and form part of each leader’s legacy. The latest of these slogans is “Chinese Dream,” coined by China’s newest leader Xi Jinping.

Simple and emotive, the term is oddly—if perhaps deliberately—similar to a term used by another global superpower—the “American Dream.” The expression is intended to provoke pride and popular support. But propagating the Chinese Dream hasn’t worked out quite the way Xi had hoped. Instead, Chinese citizens have hijacked the phrase and turned it into a symbol of China’s civic problems, not its civic ideals.

The Chinese Dream was supposed to mold Chinese citizens into “useful members of society”

In recent years, the term Chinese Dream has cropped up in Chinese scholarly articles and books, as well as in a notable New York Times editorial by Thomas Friedman. But it wasn’t until Xi used the term in a speech in November of last year that it truly caught fire. Two weeks after he was nominated as head of the CCP, Xi said in a speech in Beijing, “Nowadays, everyone is talking about the China Dream…In my view realizing the great renewal of the Chinese nation is the Chinese nation’s greatest dream in modern history.”

Chinese bloggers and commentators pounced on the expression and began debating its meaning in live forums. In March, with the term wafting through society, Xi used the word “dream” at least 23 times in his speech to accept the post of president. Xi spoke of the need to “build a strong, democratic, civilized, and harmonious modern socialist country and to attain the Chinese Dream of the great renaissance of the Chinese nation.”

Since then, Xi has wedged the term Chinese Dream into discussions with business leaders in Hainan and state visits abroad. Officials have taken the propaganda campaign even further: In April, the official voice of the party, the People’s Daily, published detailed instructions for propagating the term: Schools should hold essay competitions; scientists and philosophers should research the topic; senior officials should be educated, and Chinese writers and painters are to make “artistic masterworks” on the Chinese Dream. All of this should instill the idea, the article says, that ”the Chinese Dream is the dream of the Chinese nation, and is also the dream of every Chinese person.”

In Xi’s estimation, the Chinese Dream isn’t meant to be a collection of individuals’ hopes and aspirations. Instead, the dreams of Chinese citizens are to be shaped to fit the government’s vision, rather than the other way around. To that end, the Chinese government has tasked “educators” with uniting “the Chinese dream [with] the dreams of youth and students, to grow up and become useful members of society,” according to the People’s Daily.

The Chinese Dream has become a vessel for reformist aspirations

Unlike past slogans like “three represents” and Hu Jintao’s “scientific development,” which many Chinese citizens dismissed as lifeless party rhetoric, the Chinese Dream has taken off. The phrase is now part of a popular talent show, the Voice of the Chinese Dream. Chinese bloggers reference the term (registration in Chinese required) in discussing all things reform-minded, from revitalizing Chinese society to innovation in business.

Chinese petitioners (people who trek to Beijing to complain about local governments), journalists and ordinary citizens are also using the Chinese Dream to advocate for personal rights, an end to censorship and stronger rule of law. Asked to name their Chinese Dreams, Chinese citizens rattle off civic aspirations like ending pollution and gaining confidence in the civil court system. In Guangxi province, one woman said, “Everyone’s dream is different…It’s not something to be defined by the government.”

- The Chinese newspaper Southern Weekend used the term to advocate for stricter adherence to China’s constitution in a January article entitled, “The Chinese Dream: A dream of constitutionalism.” The piece was later censored and modified to ”The Chinese Dream is nearer to us than ever before.” Journalists at the paper demonstrated for days against the change.

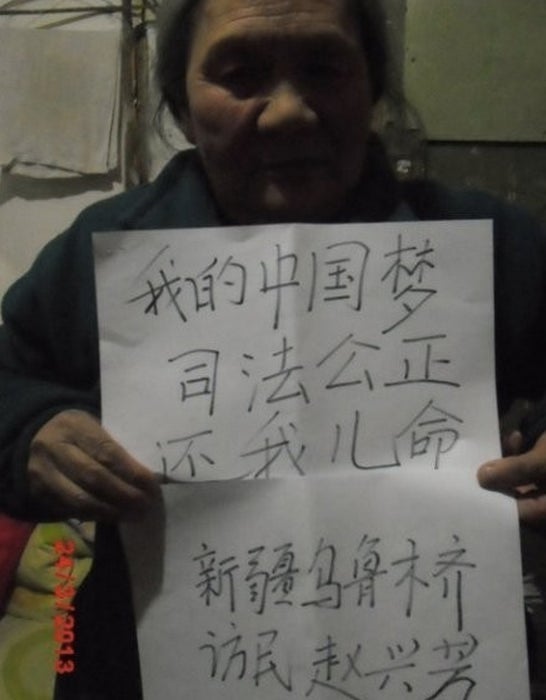

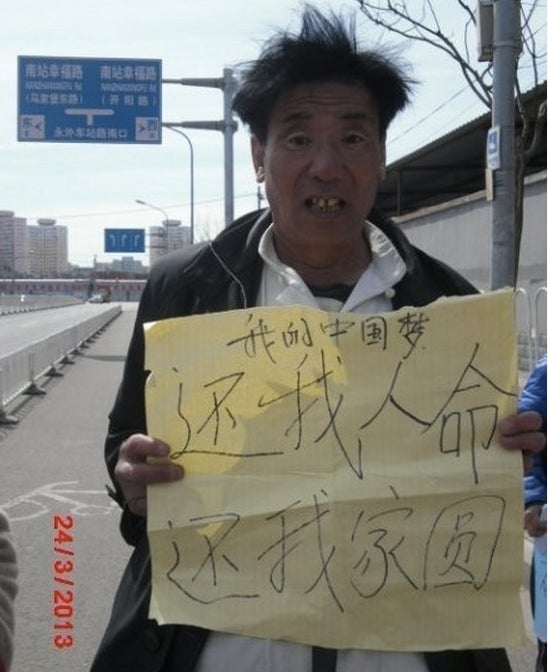

- In March, this series of photos of petitioners with signs detailing their Chinese Dreams circulated the microblog Sina Weibo:

- Last month, when regulators ordered publishers not to print a book on political life by the reformist Chinese scholar Yu Jianrong, a group of bloggers leveraged the term to criticize government censorship. One wrote (registration required) on Weibo, “The government is not smothering just one book, but smothering our “Chinese Dream.” Another, using a euphemism for being detained by police, said (registration required), “I want to treat [the official responsible] to a cup of coffee…where we can also discuss Secretary Xi’s Chinese Dream,” according to China Digital Times.

The Chinese party and military have their own version of the Chinese Dream

Disparate definitions of the Chinese Dream reflect the country’s factious political system. For some Chinese party and military officials, the Chinese Dream symbolizes China’s aspirations to rise to the top of the global international order. In 2010, senior colonel Liu Mingfu published a book titled “Chinese Dream” in which he argues China should revive its militaristic spirit to rally public support. Shortly after Xi’s November speech, the publishers introduced a new edition.

Xi has never discussed the Chinese Dream in the context of global supremacy. (In Moscow, he told students the Chinese Dream would be for the benefit of “all countries.”) But his vagueness leaves the term open for military exploitation, and Xi himself has used the term to discuss military prowess. In December, Xi said, “This Dream can be said to be the Dream of a strong nation; and for the military, it is the Dream of a strong military.” Xi has also said that the Soviet Union’s fall resulted from weak ideological discipline.

The party appears to be fighting back against public interpretations of the Dream. According to the South China Morning Post, authorities sent a directive (paywall) recently to some university professors to avoid class discussions of the “Seven Don’t Mentions.” Chinese journalist Gao Yu says the “Don’t Mentions” likely reference seven trouble areas for the party, which were identified in a nonpublic meeting earlier this year: constitutionalism, democracy, civil society, neoliberalism and Western media bias.

There is much speculation about whether Xi will bring reform to China. But his vision of the Chinese Dream suggests he is more interested in Mao-style control over the public. The question is how far disappointed citizens are willing to go in demanding their own version of the Chinese Dream.