American teachers are scrambling for ways to make kids feel safe in a country riven by politics and hate

After Donald Trump was elected US president last week, teachers reported that Hispanic and Muslim children were arriving at school in tears, worried that they or their parents would be deported, and upset about Trump’s inflammatory language dubbing them “rapists” or terrorists.

After Donald Trump was elected US president last week, teachers reported that Hispanic and Muslim children were arriving at school in tears, worried that they or their parents would be deported, and upset about Trump’s inflammatory language dubbing them “rapists” or terrorists.

Teachers and superintendents reacted by doing what educators often do: trying to create a sense of safety and belonging for all students. While this may sound like common sense, it is also backed up by research.

Camille Farrington, a senior research associate at the University of Chicago Consortium on School Research, focuses on the role of “noncognitive” factors in academic performance. Her 2012 book Teaching Adolescents to Become Learners: The Role of Noncognitive Factors in Shaping School Performance reviewed the growing body of research around what actually works in improving school performance. She found that kids need to believe a few things to succeed:

- I belong in this academic community

- My ability and competence grow with my effort

- I can succeed at this

- This work has value for me

“Each increase students’ academic perseverance and improve academic behaviors, leading to better performance as measured by higher grades,” Farrington wrote.

Teachers don’t need to read Farrington to know that kids who feel ostracized or vulnerable struggle more in school. Even before the election, teachers reported a “Trump effect”: an uptick in stress among immigrant kids responding to Trump’s rhetoric about the dangers of Mexican and Muslim immigrants.

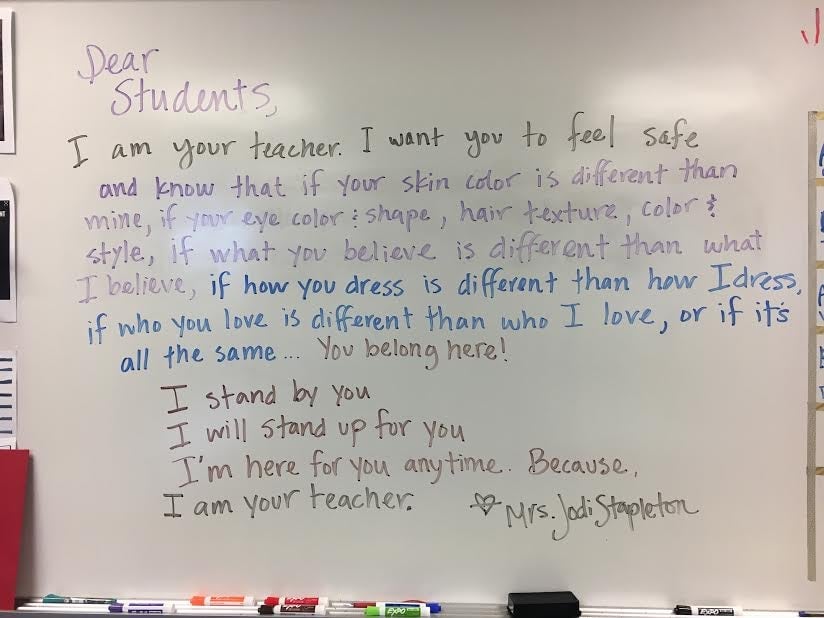

When Trump won, teachers and educators responded creatively. After eight years teaching in Maryland, Jodi Stapleton is now working at a grade school in Fort Worth, Texas. Her school is majority white, but with plenty of minority groups, including immigrants, Muslims, African Americans, and a LBGQT community. Her sense is that diversity is a “touchy” subject. So after the election she posted this:

“I didn’t get much of a response right away,” she said, which she expected since minorities were scared. But by the end of the day, students were sharing images of the poster on Twitter and seeking her out to see it in person. “I strongly believe then cannot learn in a place they don’t feel safe,” she said.

In Sacramento, teachers tried to quell anxious students by having them write to president-elect Trump, the Sacramento Bee reported. “During the election, some of the things you said made us feel offended because you don’t think good of immigrants. My family and I hope you give us the opportunity to demonstrate we are good people—please,” wrote a teenager who came to the U.S. to flee gang violence in Honduras.

A teen from Mexico said this in his letter: “During the election some of the things you said made us feel sad because you offended us without knowing us…. My family and I hope you let us stay here, because here is everything.”

Teachers expressed an emboldened sense of purpose. Christina Torres, a middle- and high-school English and drama teacher in Hawaii, wrote on her blog that there has never been a more important time to be an educator. “To unbreak these cycles of racist thought in our country, to teach our kids to challenge the existing systems that got us here, and most important to create spaces that are safe and loving in a world that may start seeming less and less accepting—this is our work.”

Maureen Costello, director of the Teaching Tolerance program at the Southern Poverty Law Center, wrote a few days after the election that for all the educational work that had to be done, safety had to come first. “Educators and parents had one job yesterday: Reassure kids and help them feel safe in the wake of the most ugly, damaging and high-stakes election in American history.”

Evidence shows that stress is bad for kids—when kids are exposed to high or even moderate levels of stress, the biology of their brains changes. They are less able to perform complex intellectual tasks and regulate their emotions. Working memory is impaired. As adults, they are at higher risk of a variety of diseases: cancer, heart disease, and emphysema, among others.

Solving for stress is step one. Longer term, the task of teaching kids how to have constructive debates, when the grown-ups around them can’t seem to, will be next, and it will be complicated. Costello said kids know that things are not ok, and they want answers. She suggested teachers remind students that “voting matters, but it’s not the only thing that does,” and the majority is not always right.

And then there is the obvious challenge of telling kids that they cannot behave like the president. “I voiced my hope that we might hear less of this kind of language coming from Mr. Trump now that he has been elected,” Anne Gunden, an eighth grade teacher in Valley Center, Kansas told EdWeek, “but I also pointed out that even if his language doesn’t change, it does not make it OK to use in our classroom.”