Teaching our children to cherish democracy will be all the more critical in Trump’s America

America’s founding fathers viewed education as an essential tool for preserving democracy. In school, Americans would learn democratic ideals, foster a meritocracy, and become savvy enough to sniff out demagogues who could threaten the republic.

America’s founding fathers viewed education as an essential tool for preserving democracy. In school, Americans would learn democratic ideals, foster a meritocracy, and become savvy enough to sniff out demagogues who could threaten the republic.

But America’s schools are failing at moving the US toward a more perfect union.

How else to explain the startling lack of civics knowledge among today’s Americans? The disturbing new research suggesting a widespread attitude of indifference to democratic systems? The preference, by more than a quarter of the American voting public, for a presidential candidate who repeatedly challenged American constitutional values? The abstention of the 42% who didn’t vote, skirting what is arguably an adult citizen’s most important responsibility?

At the same time, public education is struggling to come up with a narrative of the American experience that encompasses the expanding diversity of the country’s population. To some, the definition of what it is to be American, as it’s taught in the classroom, feels too limiting; to others, it’s being stretched beyond recognition. Either way, the overall effect is disorienting, and public discourse is feeling the strain.

“As our nation becomes increasingly diverse, we don’t really have any choice but to find ways to reach across racial and ethnic divides to find common ground,” says Richard Kahlenberg, senior fellow at The Century Foundation, a progressive public-policy think tank.

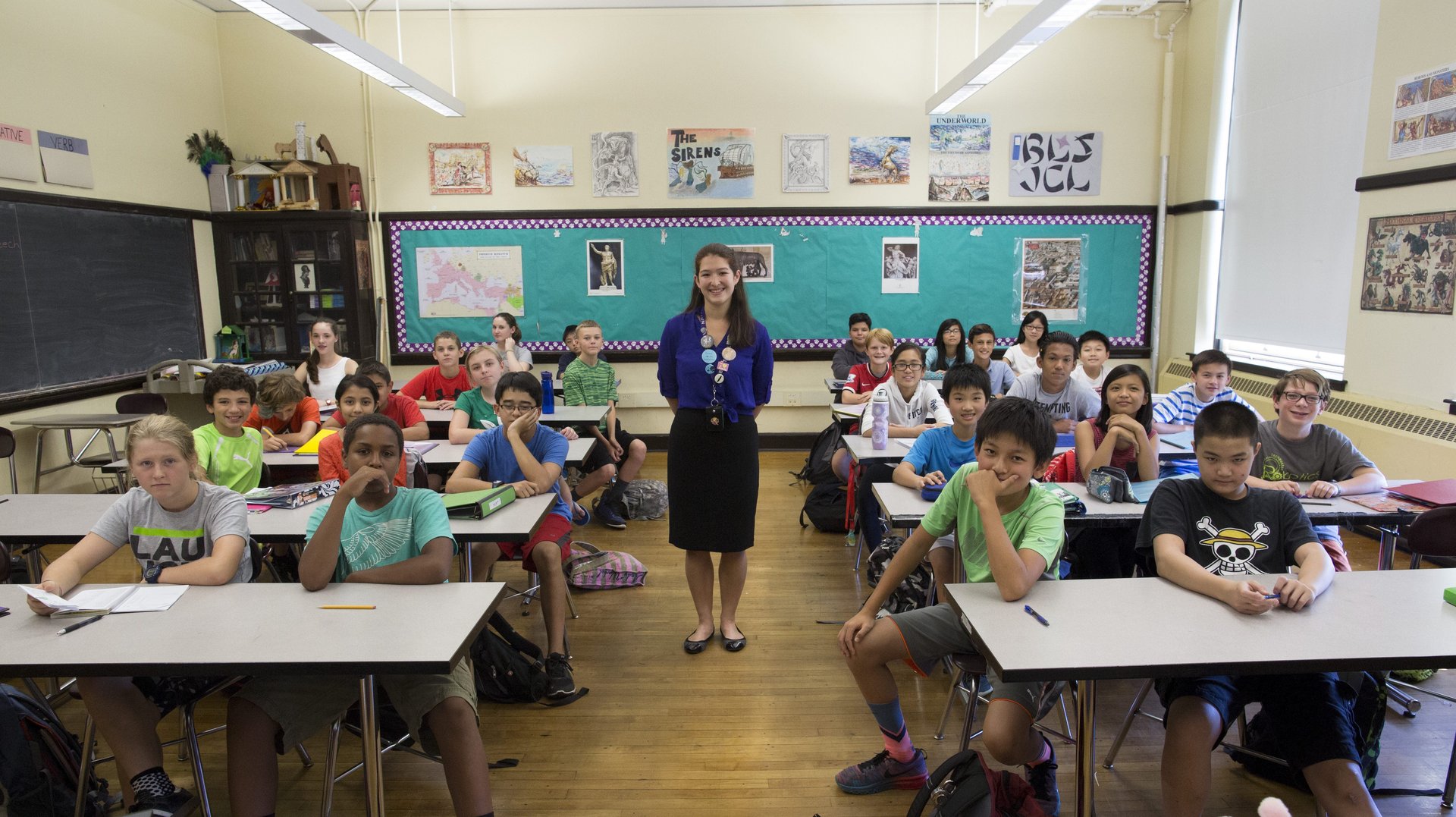

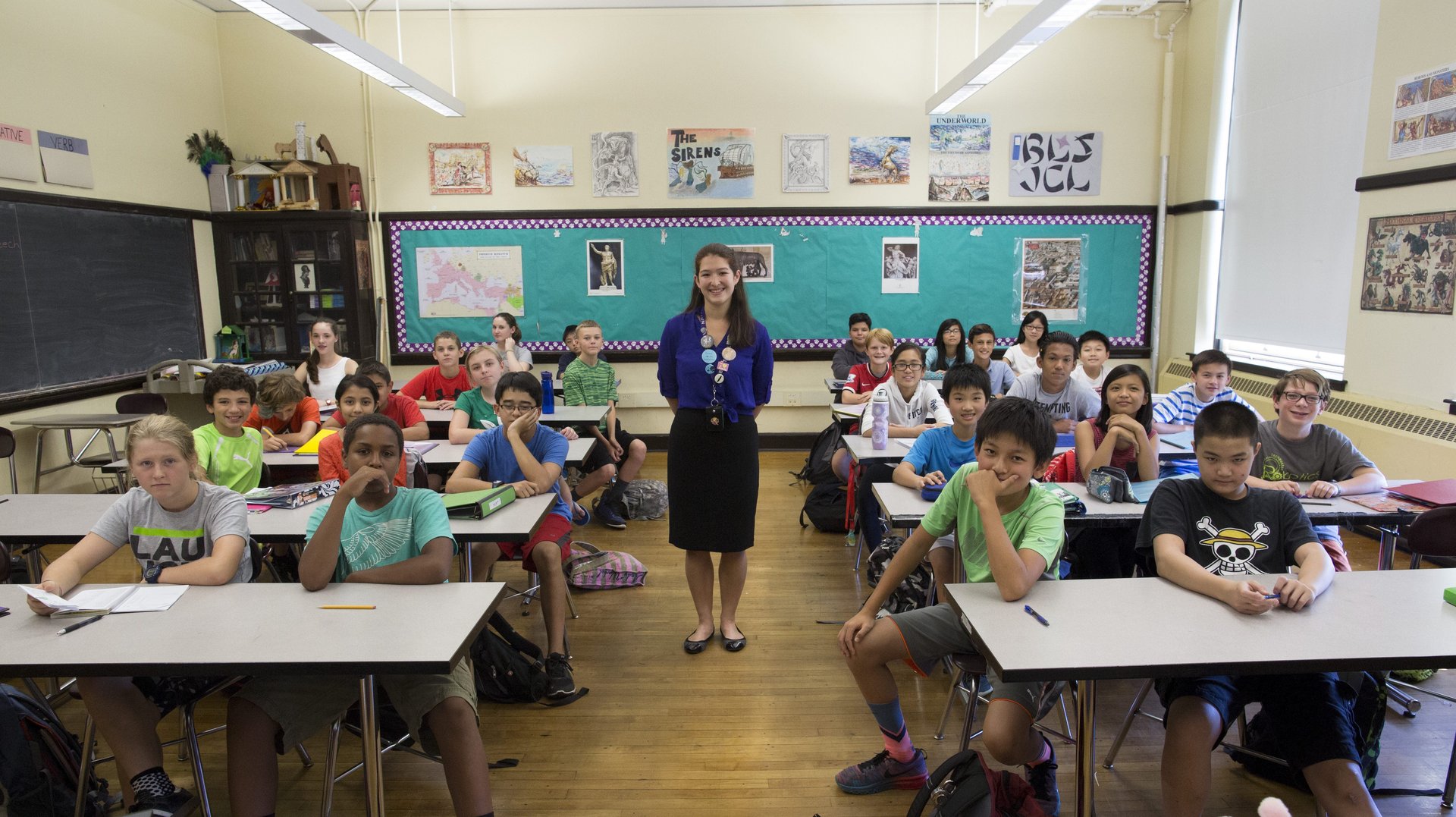

As one of the few neutral zones where Americans of all stripes meet, public schools are a good place to take that on.

A Sputnik moment

Kahlenberg has called Trump’s election a “Sputnik moment” that should spur the same kind of investment in civics education as the Soviet satellite did for science back in the late 1950s and 1960s. As the US seeks to compete with other world economies, practical subjects such as reading and math have crowded out civics lessons, he argued in a recent report.

That strategy has taken its toll. Only a third of Americans can name the three branches of government, according to a 2015 survey by the Annenberg Public Policy Center at the University of Pennsylvania. Perhaps even more worrisome, a large number of Americans are straying from the founders’ democratic ideals. Roughly 30% of those polled believe their Constitution need not stop the government from interfering in religious practices and public protests if they are offensive or un-American—in clear contradiction to what the Constitution says.

Other polls show a disturbing bent towards authoritarianism. One in six US citizens agree that it would be “good” or “very good” for the army to rule, up from one in 16 in 1995, according to another analysis, which was based on World Values Surveys and published in the Journal of Democracy in July. Yet another alarming survey, conducted by PRRI and the Brookings Institution in May and April, found that nearly 60% of Americans have authoritarian tendencies. More than half of those with a highly authoritarian streak said the US needs a leader willing to break the rules to set the country on track.

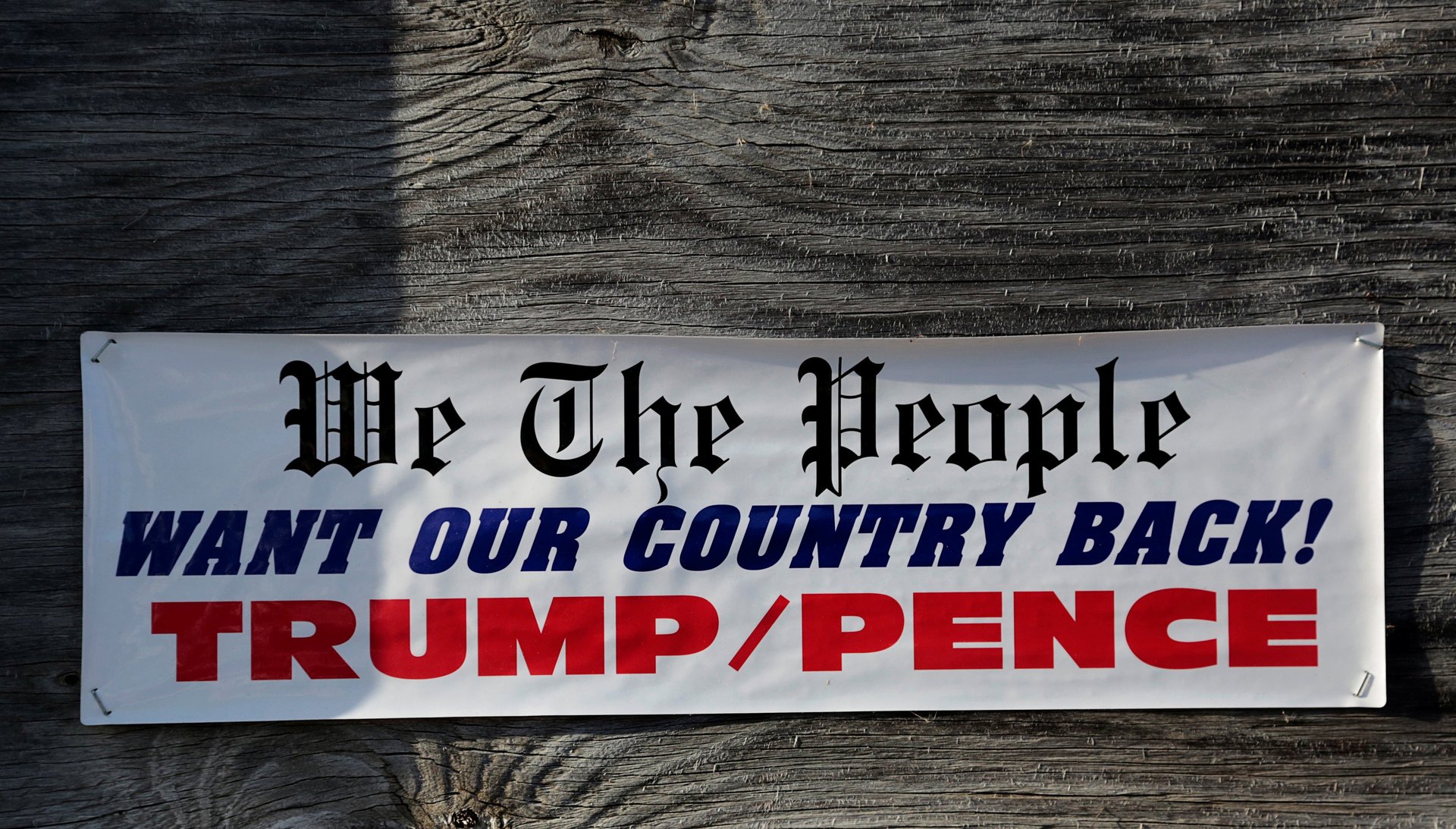

Trump’s America

They might have just gotten that kind of leader in Trump, who throughout the campaign displayed an inclination to dispense with longstanding democratic norms. (His threat to jail his political opponent and his refusal to commit to the election results are two examples of that.)

To be sure, president Trump might distance himself from his brash political candidate persona once he takes over the Oval Office. But the fact remains that the millions of Americans who voted for him, some whom see themselves as patriots for doing so, didn’t feel that his attacks on core American principles disqualified him from filling the highest office in the land. Why?

Pundits and academics have been struggling with that question even before Trump’s electoral victory. Jonathan Haidt, a business ethics professor at New York University’s Stern School of Business, suggests the answer lies beyond the racism and xenophobia espoused by some Trump supporters, or the economic desperation of others. He points to the work of Karen Stenner, a former Princeton University professor who developed a simple formula that can explain what is going on: intolerance = authoritarianism × threat (pdf).

These days, authoritarian-prone Americans are definitely feeling under threat. The PRRI/Brookings survey found that more than 60% of respondents with highly authoritarian leanings believe the American way of life has gone down hill from the 1950s. Roughly the same proportion live in fear that they or their families could be attacked by terrorists or violent criminals. They believe Islam is un-American, and interacting with non-English speaking immigrants bothers them.

Haidt sees that kind of behavior as a reaction to the rise of a cosmopolitan citizenry that, in the eyes of authoritarians, has given up allegiance to its country of origin and culture in favor of broader global society. “Authoritarians are not being selfish,” he writes in The American Interest. “They are not trying to protect their wallets or even their families. They are trying to protect their group or society.” (Italics his.)

Since the source of the threat is diversity, trying to better acquaint insurgent authoritarians with “the other” will only make things worse, he concludes. He quotes Stenner:

“[We] can best limit intolerance of difference by parading, talking about, and applauding our sameness. Ultimately, nothing inspires greater tolerance from the intolerant than an abundance of common and unifying beliefs, practices, rituals, institutions, and processes.”

E pluribus unum

For public education, the implication is that schools should avoid polices that single out difference, such as multicultural curriculums and bilingual programs. Robert Pondiscio, a senior fellow at the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, suggests instead to revive the “melting pot” metaphor, making it “more capacious and generous” than the original.

The melting pot image was forged during a period in which the US was taking in millions of European immigrants, and for a long time served as shorthand for the American experience. But in the 1960s, social scientists and minorities began to question the assumption that immigrants were melding into the dominant culture—and whether they should. The pot was replaced by the “salad bowl,” to represent American society as an assemblage of different ingredients, each retaining its characteristics but coated with a common dressing.

Now there’s pushback against the salad bowl concept from people who believe it favors diversity to the point of undermining American identity. Bruce Thornton, a professor at California State University in Fresno, expresses that sentiment in a 2012 piece published by the Hoover Institution.

[S]o the common identity shaped by the Constitution, the English language, and the history, mores, and heroes of America gives way to multifarious, increasingly fragmented micro-identities. But without loyalty to the common core values and ideals upon which national identity is founded, without a commitment to the non-negotiable foundational beliefs that transcend special interests, without the sense of a shared destiny and goals, a nation starts to weaken as its people see no goods beyond their own groups’ interests and successes.

It doesn’t sound all that different from the threat to society perceived by authoritarians described by Haidt. Against that kind of backlash, “it’s worth asking whether the best way to increase tolerance and honor diversity is by focusing on shared civic ideals,” said Pondiscio.

Will they listen?

Getting schools to focus on Americans’ shared identity won’t be easy. Take the Rust Belt towns that switched parties to elect Trump, becoming one of the biggest election stories. People in these communities tend to see their local schools as a source of local identity; they don’t take well to outside edicts, particularly those that originate in big cities, says Katherine Cramer, a professor at University of Wisconsin-Madison whose research for the past 10 years has involved chatting with rural Midwest residents. “How do you not make it sound like ‘Oh, yet again urbanites are telling us that we are backward and we need to be brought back in line with urban society?’” she said.

Trump hasn’t elaborated on his education policies, but he has vowed to get rid of the national academic standards known as “common core.” “Education has to be at a local level,” he says in this campaign spot. “We cannot have the bureaucrats in Washington telling you how to manage your child’s education.”

American identities

Convincing Trump supporters on the shared-identity question is only half the hurdle. The melting pot image doesn’t have a very good reputation among minorities, many of whom would argue that they were never allowed to fully blend into the US’s bubbling cauldron. They feel just as marginalized and misunderstood as Trump rural voters—and also threatened, now that a candidate who was openly hostile to (or plainly ignorant of) their communities has won the presidency.

Americans in these communities want to be acknowledged, and for many of them, that means including their accomplishments in K-12 curriculums.

They’re unlikely to back down, as demonstrated by an ongoing textbook fight in Texas. The state’s population is nearly 40% Hispanic, including people whose ancestors, before the American Revolution, settled in what is now Texas. Hispanic activists and scholars have long argued that this experience should be reflected in what Texas children are learning in school. They say that rather than displace American values, ethnic studies are an opportunity to teach all Americans how connected they are through history.

“Learning about each other’s diversity is a sign of strength for our nation,” says Celina Moreno, a lawyer at Latino civil rights group MALDEF.

MALDEF and other groups involved in the Texas textbook dispute won a small victory in 2015, when the State Board of Education made a call for Mexican-American history textbooks for optional courses. The sole submission, however, contained factual errors and assertions such as the one below:

Stereotypically, Mexicans were viewed as lazy compared to European or American workers… Mexican laborers were not reared to put in a full day’s work so vigorously. There was a cultural attitude of “mañana,” or “tomorrow,” when it came to high-gear production. It was also traditional to skip work on Mondays, and drinking on the job could be a problem.

Hispanic activists revolted against the book, calling it racist and inaccurate. In a telling sign of the country’s gaping cultural divide, some just didn’t see their point. “It’s really kind of perplexing as to what all the controversy is,” education board member David Bradley told the Texas Tribune. “I am French-Irish, and you don’t see the French or the Irish pounding the table wanting special treatment, do you?” He also indicated in an email obtained through an open records request that board members should skip the meeting to discuss the text to “deny the Hispanics a record vote,” according to the Tribune.

He was the only member who didn’t show up to the Nov. 16 meeting. Dozens of Hispanic activists attended. They prevailed: The board rejected the book. But the curriculum remains unchanged, so they’re still losing on that front.

Research shows that minorities benefit when they learn about their communities. A paper published by Stanford Center for Education Policy Analysis earlier this year looked at the effects of ethnic studies courses in San Francisco high schools and found that they increased ninth-grade attendance by 21% and GPA by 1.4 grade points. Another one, from the University of Arizona, showed that students who took Mexican-American studies courses were more likely to pass state standardized texts and graduate from high school. (Some academics suggest that white students also benefit from the exposure.)

The gains go beyond report cards, says Albert Camarillo, a Stanford University professor credited with helping start the Mexican-American studies field. “It gives people a sense that they too are part of the fabric of the larger society, rather than marginal people on the side of it,” he says.

That feeling might go a long way in turning out minorities to the polls. Hispanics and Asians, two of the fastest-growing demographic groups, vote at much lower rates than their white peers. Their failure to fully participate in the political process is as big a risk to representative democracy as an authoritarian insurgency.

Learning together

In the end, the curriculum may be less important than the overall school experience. As Thurgood Marshall, the country’s first black Supreme Court justice, put it: “Unless our children begin to learn together, there is little hope that our people will ever learn to live together.”

He wrote that in a 1974 opinion on a case about school segregation. More than 40 years later, US classrooms are still not integrated. In fact, the share of intensely segregated schools, those that are 90% to 100% nonwhite, has been rising in past decades, according to a May report by the Civil Rights Project at the University of California, Los Angeles.

That kind of segregation, says Kahlenberg, of the Century Foundation, “undercuts the message that in a democracy everyone is equal and should have equal voice.”

But that’s the message Americans need to figure out how to restore, whether by civics courses or ethnic studies, school integration, or any other methods, if they want to preserve their democracy.