Donald Trump’s attorney general could terminate the rule that protects state-legalized marijuana

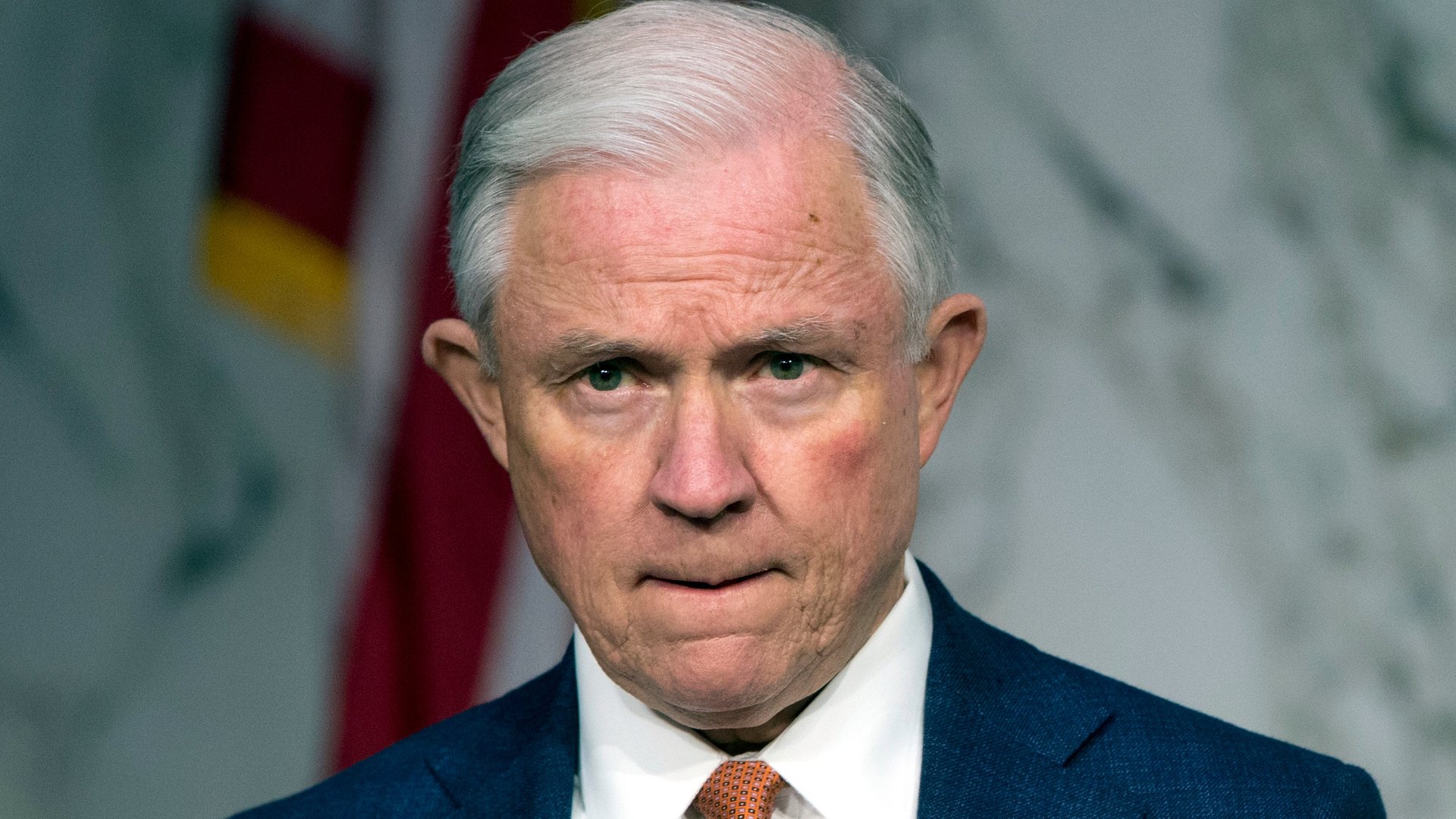

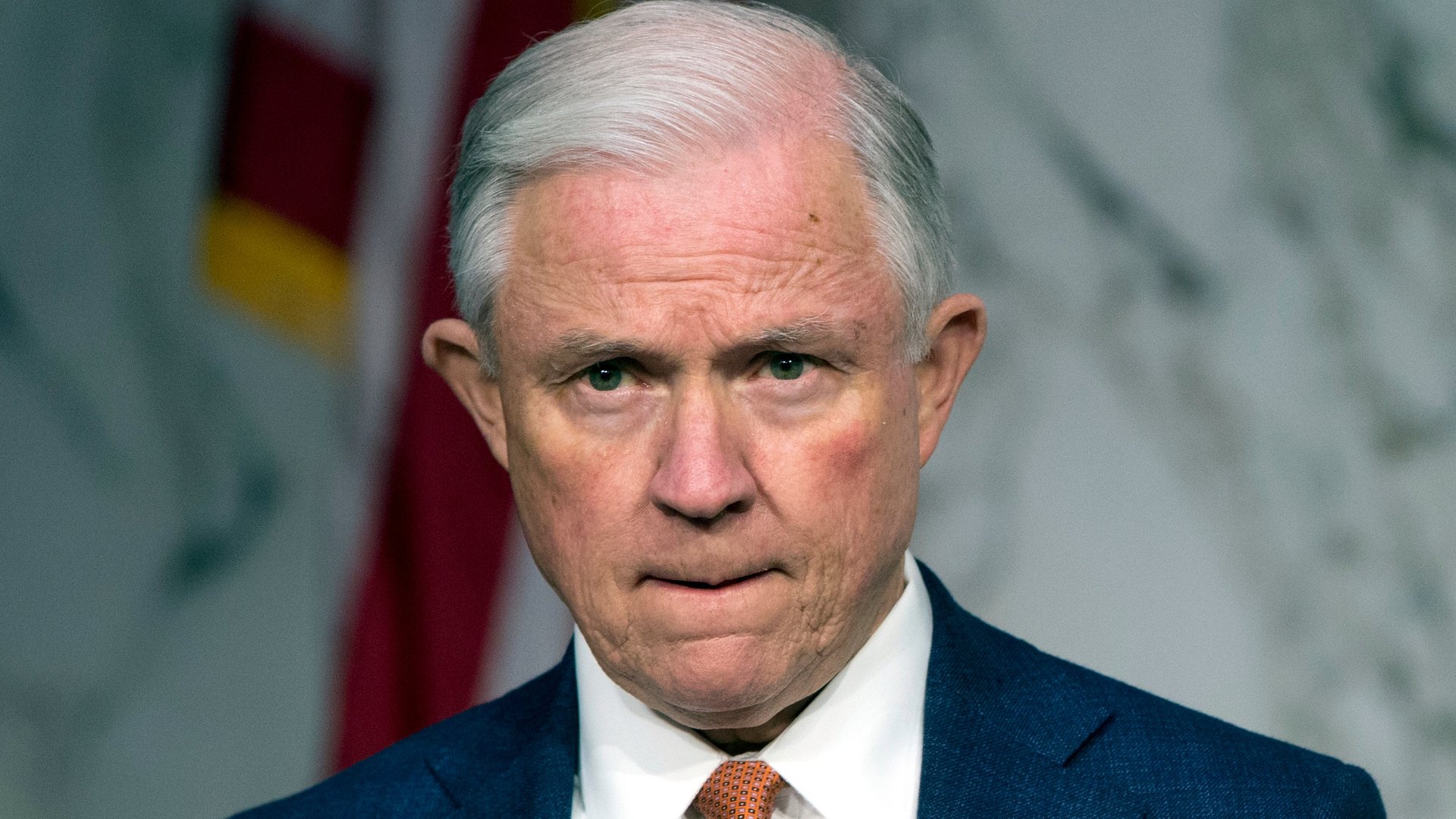

The US marijuana industry’s vibrant growth in the grey area of federalism could be threatened by president-elect Donald Trump and his preferred choice for attorney general, Alabama senator Jeff Sessions.

The US marijuana industry’s vibrant growth in the grey area of federalism could be threatened by president-elect Donald Trump and his preferred choice for attorney general, Alabama senator Jeff Sessions.

Sessions, an early backer of Trump’s presidential campaign and an outspoken critic of US immigration policy, is also an opponent of marijuana legalization. He has criticized the Obama administration’s approach to drug policy, including its tolerance of states where voters have approved the use of marijuana for medical or recreational purposes.

“It is false that marijuana use doesn’t lead people to more drug use,” Sessions argued in a speech earlier this year. (Researchers are split.) “It is already causing a disturbance in the states that have made it legal. I think we need to be careful about this.”

Marijuana is still considered a controlled substance under federal law, but a wave of states have relaxed or eliminated prohibitions on the plant and products derived from it. Some see a tipping point at hand on a national level; on election day, eight of nine major initiatives to legalize recreational or medical marijuana passed.

Yet the primary reason that the professional and well-publicized marketers of marijuana in these states aren’t being arrested by federal agents and prosecuted in federal court is a policy put in place under president Obama. A 2013 memorandum (pdf) written by deputy attorney general James M. Cole directed federal prosecutors to focus their efforts on criminal enterprises, with the implicit message to tolerate state-regulated marijuana dealers.

That rule hasn’t prevented marijuana operations from being raided by Drug Enforcement Administration agents or local cops, but it has at least prevented those companies from being prosecuted. An attorney general Sessions, however, could issue a new directive that would give prosecutors in states with legal marijuana a freer hand to prosecute marijuana companies, or even require them to do so.

Still, there are reasons to believe he won’t, starting with the fact that there are now so many states with legal recreational or medical marijuana, and functional businesses supporting the marijuana industry. Changing the facts on the ground promises to be a tough political fight, and it may not be high on the priority list for Trump or Sessions, who seem more interested in addressing immigration rules early in his term.

“Voters in 28 states have chosen programs that shift cannabis from the criminal market to highly regulated, tax-paying businesses,” the executive director of the National Cannabis Industry Association, Aaron Smith, said in a statement. ”Senator Sessions has long advocated for state sovereignty, and we look forward to working with him to ensure that states’ rights and voter choices on cannabis are respected.”

For what it’s worth, Trump himself has generally seemed supportive of marijuana, or at least not inclined to prosecute it. The NCIA sent its members a collection of Trump’s marijuana quotes shortly after the election, noting that he said he is “in favor of medical marijuana 100%” and “I really believe we should leave it up to the states.”

Congress, too, could act to prevent a harsh crackdown on states with marijuana industries. Today, half of senators and 60% of representatives hail from states that have legalized some kind of marijuana access. In 2014, Congress has passed a provision co-authored by California Republican Dana Rohrabacher that forbids the Department of Justice from spending any money to disrupt state-regulated medical marijuana providers. But because the DEA has interpreted the law as referring to states themselves, and not marijuana dispensaries or other organizations, the provision has not been able to entirely prevent agency raids. Efforts to pass a more restrictive funding ban haven’t been successful, but may find more backers in a new Congress with more Democratic representatives.

Sessions has already proved a controversial choice as the top law enforcement official. As prosecutor in the 1980s, he was nominated to a federal judgeship by Ronald Reagan, but failed to earn Senate confirmation when lawmakers questioned his judgement on race, including one case where he charged black voting rights activists with voter fraud but saw the charges rejected by a jury.