“We are going, in the United States, to legalize marijuana nationally, and roughly along the alcohol model, and there’s a good chance that people in 25 to 40 years will look back and shake their heads and ask, what were you thinking? Why did you think it was a good idea to create an industry of titans to market this drug?”

Jonathan Caulkins, a drug policy expert, addressed a room at the National Cannabis Science and Policy Summit full of the people doing the thinking—marijuana legalization advocates, public health researchers, state regulators, and investors hoping to take advantage of the anticipated marijuana boom.

A majority of people in the US now support marijuana legalization and that development is due to a confluence of factors: Growing awareness that the “war on drugs” has done huge damage to the poor and minorities without meaningfully checking access to drugs; the plight of chronically ill patients seeking access to medical marijuana; and the recognition of recreational marijuana and the tax revenues that come with it.

Oregon, Washington and Colorado have implemented robust medical and recreational legal systems. Vermont’s legislature may do the same. Canada’s new prime minister, Justin Trudeau, has announced his plan to move to legalization. In 2016, recreational marijuana is on the ballot in Arizona, Maine, Massachusetts, Nevada and, most importantly, California.

In California, which already has a loosely-regulated medical marijuana regime, voters are expected in November to okay a new industry infrastructure that legalizes marijuana and hemp and establishes state agencies to oversee licensing and regulation. When they do, it will be something of a tipping point, with the federal government forced to play catch-up.

Caulkins and the organizers of the summit fear that, after years of pushing for saner drug policy, the new rules might allow for corporations to expand consumption of marijuana by the people least prepared to use it. The comparison is not so much to drugs like tobacco or alcohol but to so-called “temptation goods,” such as sugary snacks and soda, video games or pornography.

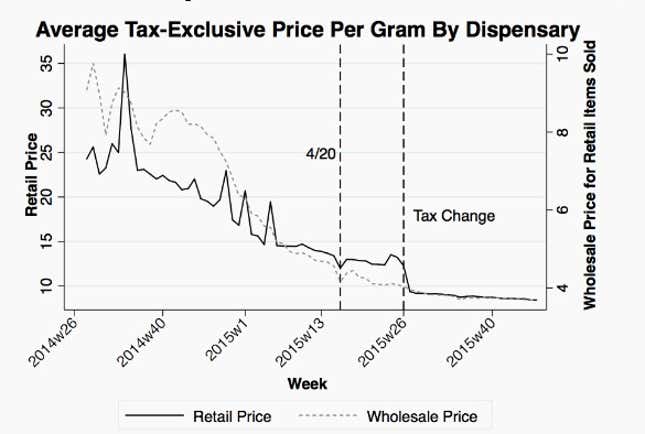

While marijuana legalization in the US has yet to show signs of major problems, researchers agree that it definitely sends the price of the drug plunging, increasing access:

Experts draw a distinction between the old, exaggerated health risks that scientists say are largely myth, and the real uncertainty around behavior-changing dependency once access becomes easier. Thanks in part to restrictions on research, rigorous empirical data on marijuana dosage, potency and long-term use is limited compared to other substances.

“The simple choice between prohibition and legalization does not exhaust the policy space,” said Mark Kleiman, the chair of the conference who helped Washington write its cannabis regulations. “Varieties of legalization can be more or less effective in getting rid of the harms of prohibition, and more or less cautious with respect to the possible harms from increased access.”

States seem unprepared to regulate the drug. Many fear that in a capital-driven marijuana industry, companies will quickly co-opt their regulators. ”The tax and industrial policies at the federal and state levels are what determines whether big marijuana grows or not,” Miles Light, the co-founder of the Marijuana Policy Group, which consults for Colorado’s state regulators, said during one panel. State governments, he said, “are nowhere near prepared.”

Many jurisdictions are overestimating the benefits of marijuana taxes without accounting for the costs of increased demand. The challenges of standardizing products—by the amount of THC? by weight? and what about edibles?—and taxing them appropriately are myriad. At the same time, they can be underestimating the cost of public education on the dangers of drugged driving or the cost of treatment for dependency issues.

“It’s not even clear costs will exceed savings,” said Greg Midgette, a RAND corporation analyst who studied Vermont’s options on legalizing marijuana.

Even those who think that full-scale legalization isn’t inevitable believe better strategies are needed. Stanford Law School’s Robert MacCoun warned of negative public reaction if marijuana consumption were to spiral out of control in Washington or Oregon. “After years of saying ‘we don’t need a criminal justice approach, we need a public health approach,’ well, now we need to have a public health approach,” he said.

Strategies designed to limit rapid market expansion include government monopolies akin to the Gothenburg System, non-profit production only, or cooperatives. But many politicians seem to concede that market forces are inevitable when it comes to putting together the coalition needed to overturn existing laws.

“I don’t know that we need to squelch competition. I don’t want to open it up to big marijuana—big marijuana is what we’ve got now with drug cartels,” Oregon congressman Earl Blumenauer said. “Oregon is trying to have a varied marketplace, not squeeze out the little guys, but not stifle innovation.” He said he expects that marijuana will someday be a luxury good like the craft beer and wine sold in his state.

Blumenauer already bets Oregon wine and beer in friendly wagers with other politicos; no word yet when he will be able to wager an ounce of Blue Dream pot instead of a case of Williamette Valley pinot noir.