The media needs a ratings system to steer readers away from clickbait and toward quality journalism

Once an editorial piece is published, it carries “signals” that express its quality. But the reliability of these indicators varies widely.

Once an editorial piece is published, it carries “signals” that express its quality. But the reliability of these indicators varies widely.

In a previous Monday Note, I listed signals that could, in an ideal world, be attached to a news item during its production (see “Signals of Editorial Quality“). This assumed publishers would agree on a common language to express the quality of their output at the CMS level—and accordingly generate reader and advertiser revenue.

Reality hasn’t (yet) been kind to the idea. Unlike telecommunications or Big Pharma—industries known to collaborate or even collude with great enthusiasm—news publishers never engaged in such behaviors, and they rarely came up with collective solutions, even when forced to address their industry’s most burning issues.

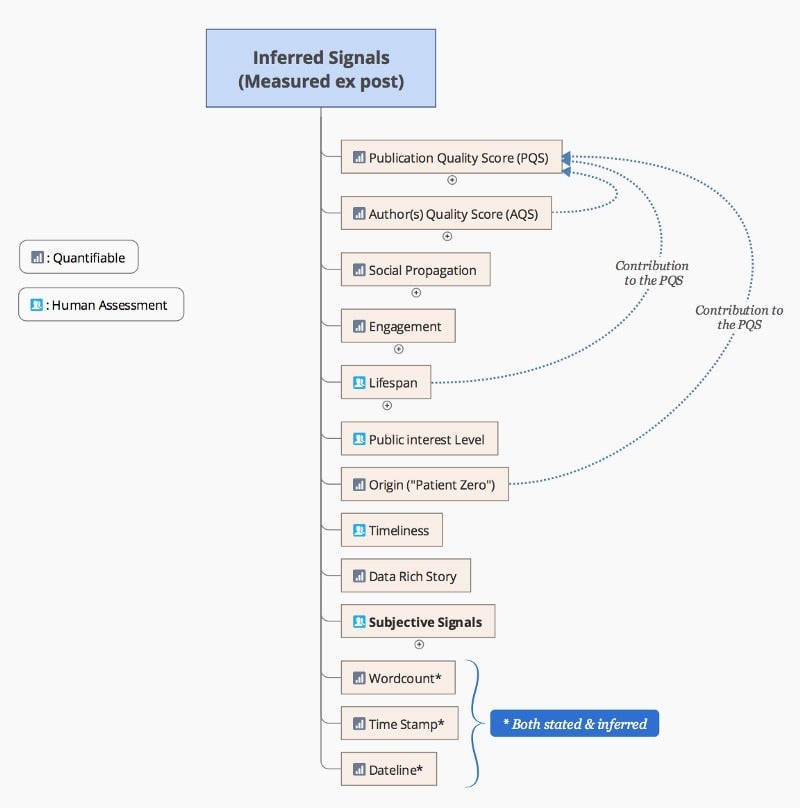

Therefore, generating quality signals for news calls for an ex-post, after-the-fact process that infers signals once the material (text, video, multimedia) is published. This option carries its own share of uncertainties. It isn’t always clear what the most relevant, most obtainable signals are—or which ones are less susceptible to tampering.

When working on a list of “inferred signals,” I made an arbitrary classification separating “machine-quantifiable” signals from the ones that must be collected by editors.

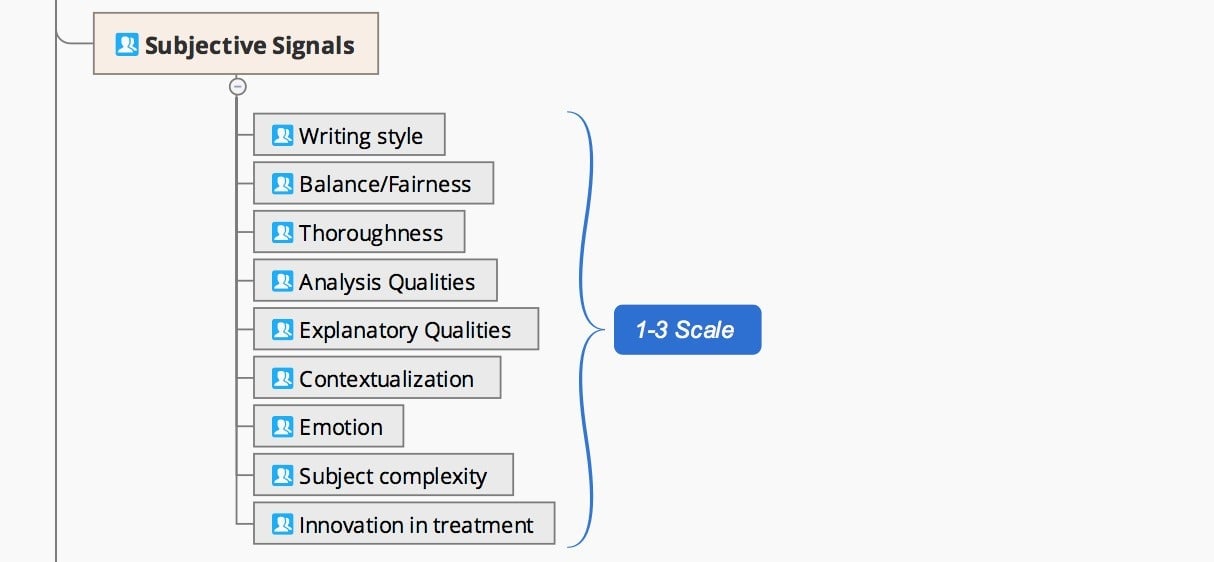

In my project at Stanford’s JSK Fellowship, human assessment is part of an automated process involving machine learning. In the same way that a neural network can be taught to recognize cats by being shown thousands of images labeled as “cats,” I assume a neural network can be taught to recognize a good piece of journalism as long as we create well-defined labels for the training process. As always, the devil lies in the details. In future Monday Notes, I will address specific questions pertaining to the machine learning/neural network part of the solution.

Today, we’ll focus on the tentative list of “inferred signals.”

The Publication Quality Score

The weightiest contribution to the overall quality of a piece of journalism is the quality of its creator, hence what I call the “Publication Quality Score” (PQS). How do we decide that website A is “better” that legacy publication B?

The PQS is a composite of several sub-indicators. These can include the number of awards collected over time. Measuring the number of Pulitzer Prizes snatched by large outlets only gives a partial picture of the answer; that number can mislead when it favors big brands. I found out that, in the United States alone, there are about… 250 different journalism awards. Even if we limit ourselves to the first 10 or 20 biggest ones, we might still end up with a pretty good indication of how a news organization is viewed by its peers.

Newsroom staffing can also serve as an indicator of commitment to quality. Easily measurable, it can be weighted by ratios such as the size of the community served—even if this index risks favoring large organizations.

Others indicators contribute to the Publication Quality Score: the most determining one is the Authors Quality Score (AQS). It is fairly easy to assess the quality or notoriety of an author. Among sub-indicators, we’ll find awards again. For journalism, novels, or documentaries, awards provide a reliable idea of the author’s notoriety. This is to be weighted by their social footprint: activity on various platforms, number of followers, retweets, etc.

Another contributor to the Publication Quality Score is the lifespan of a story. By lifespan, I mean the ability of a piece to remain a “classic” for a long time; it could be a unique profile, or a report (see this selection of 100 “Exceptional Works of Journalism“ compiled by the Atlantic or this list assembled by Kevin Kelly). I’m not referring to pieces always reaching such high level, but the fact remains that, several times a year, newsrooms large or small produce landmark pieces. A limit of the lifespan sub-signal is its reliance on human judgement: today, no machine is able to predict a story’s staying power.

The last contributor to the overall quality of a publication is the origin (“Patient Zero“) indicator. Today, a great story takes only minutes to find its way to others publications’ news streams. Most of the time, credit gets lost in the process. But it is fairly easy to automatically track down the true origin of a piece. A publication that accumulates “Patient Zero” stories will get a correspondingly solid quality score.

Other indicators

Social propagation is already a widely used indicator. It involves measuring the volume and speed of shares. I view it more as a popularity indicator at a given moment than as a long-lasting quality clue. It should have a low weight in the model.

The engagement metric combines the most critical values in assessing quality: actual reading time, and the propensity of the reader to comment, annotate, or even email the piece to a friend. (Technicalities to be discussed at a later time).

Public interest level can only be evaluated by a human. It is an important element—a key differentiator for a story to emerge from the static of commodity news.

The level of data contained in a piece usually indicates the depth of research; a piece with several graphics is more likely to be well-documented than a “dry” one…

The subjective signals bucket involves editorial judgements in the literal sense. Again, I don’t see algorithms able to make a cold-blooded evaluation of how well a story is written, balanced, etc.

The final three indicators of the list (word count, time stamp, and dateline) can be stated by publishers and/or inferred by a third party.

As I said before, the above is but a glimpse into a long, arduous research effort. Finding stable, relatively undisputed indicators that are foolproof enough and reasonably obtainable as well is quite a challenge. But the more I get into these issues, the more I’m convinced that betting on quality, and finding ways to assign a higher economic value to good journalism, is the only way to save it.