A Human Rights Watch report details first-hand accounts of torture under China’s anti-corruption campaign

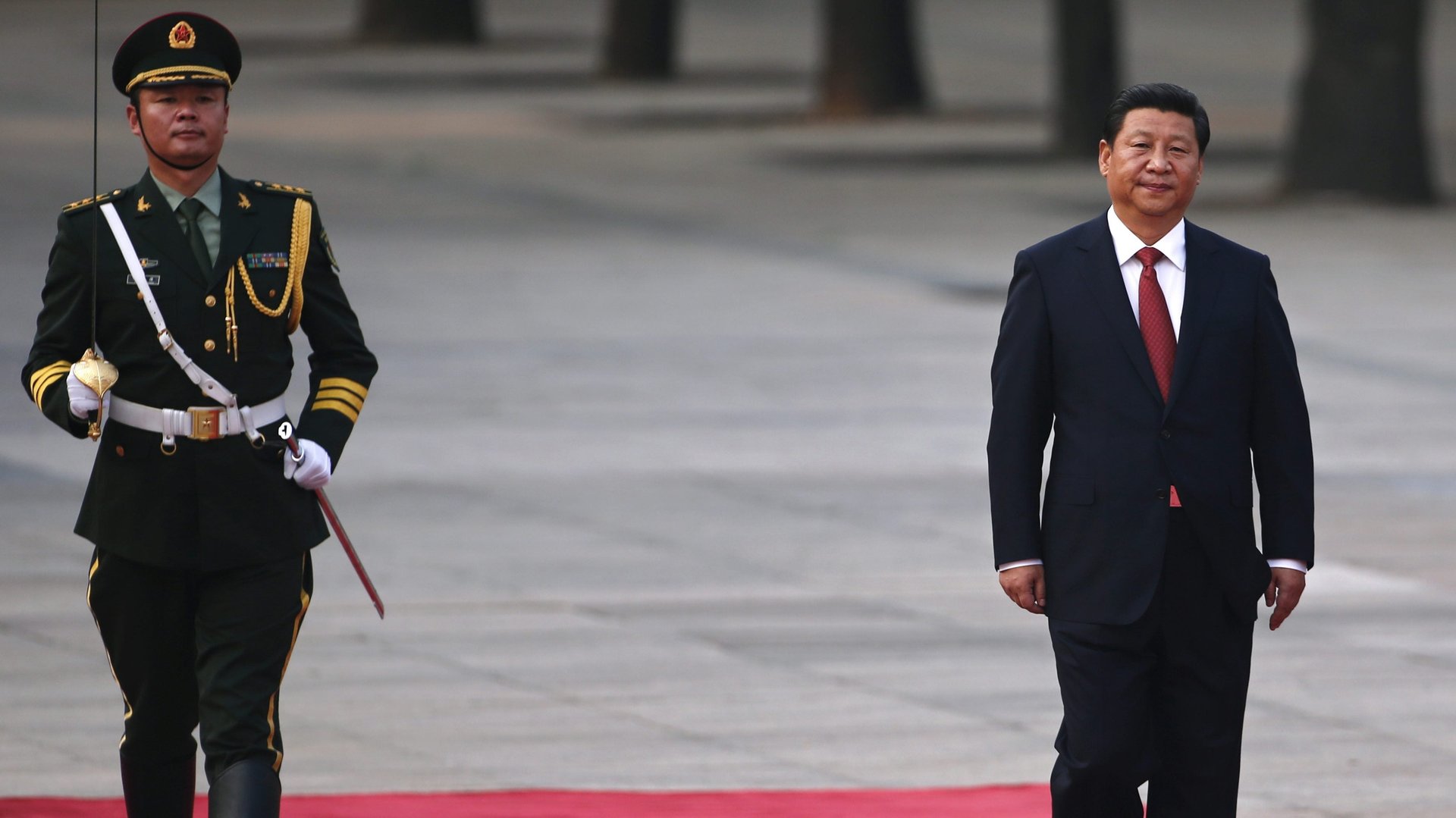

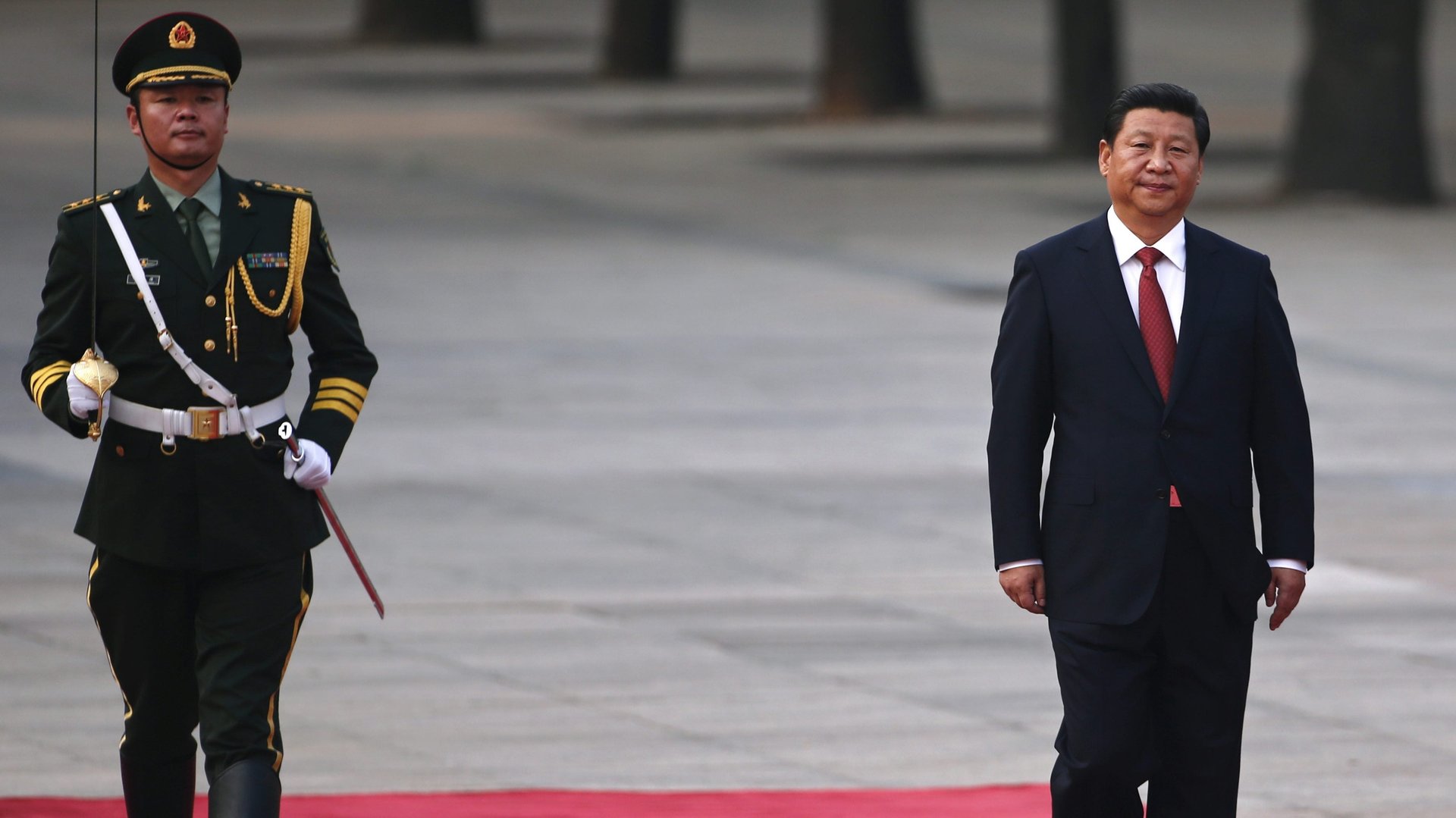

Since taking the helm in 2012, Chinese president Xi Jinping has netted hundreds of high-ranking Communist Party officials and thousands more from lower levels in his sweeping, seemingly neverending anti-corruption drive. The campaign is built upon an illegal detention system known as shuanggui.

Since taking the helm in 2012, Chinese president Xi Jinping has netted hundreds of high-ranking Communist Party officials and thousands more from lower levels in his sweeping, seemingly neverending anti-corruption drive. The campaign is built upon an illegal detention system known as shuanggui.

Allegedly corrupt officials suffer abuses including prolonged sleep deprivation, stress positions, deprivation of water and food, and severe beatings. They are denied any legal protection, including access to a lawyer, in the extra-judicial detention system used to coerce confessions, a new report from Human Rights Watch finds.

The report, published today (Dec. 6), is the first to contain first-hand interviews with detainees. HRW interviewed 21 people, including former shuanggui detainees, their family members, and lawyers who had represented them. All of them, except for a former procurator, said that shuanggui detainees are subjected to torture.

Shuanggui, or “double designated,” refers to the notice informing party members to appear at a designated place at a designated time for questioning. It dates back to 1990 and has no basis in Chinese law. The Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI), the party’s internal disciplinary watchdog, is empowered to use the measure to detain and investigate all 88 million party members for alleged “disciplinary violations,” usually a euphemism for corruption.

An estimated 10% to 20% of all cases investigated by the CCDI and its local bureaus (CDIs) involved the use of shuanggui. The HRW report said that as more corruption investigations have been filed under Xi, more individuals are likely to have been subjected to shuanggui.

Shuanggui often begins with an individual’s disappearance, without any notification to his or her family members. Torture in confinement lasts indefinitely until the person confesses, former shuanggui detainees told HRW. The report also details what the shuanggui locations look like:

Shuanggui facilities are typically rooms in hostels with special features, such as padded walls or a lack of windows, to prevent suicides or escapes. Detainees are guarded round-the-clock by shifts of officials, often put together in an ad hoc fashion for this purpose, and subjected to interrogations by CDI officers.

One former detainee told HRW that he was forced to alternate between periods of prolonged sitting and standing:

If you sit you have to sit for 12 hours straight, if you stand then you have to stand for 12 hours as well. So my legs became swollen, and my buttocks [started oozing pus]… They used gauze pads on my wet, festering buttocks.

Another spoke of being restrained in a “tiger chair,” a metal chair with handcuffs and leg irons:

For nine days and nine nights I sat in tiger chairs; and urinated and defecated into adult diapers… for over a hundred hours, whether it’s day or night, they took turns interrogating me.

Others said that water and food were used as means of control and coercion:

In the beginning they let you drink water, but after three to four days, they said, “You want to talk about your problems?” and if you weren’t able to tell them, they didn’t let you drink it. If you did, he used one of those disposable cups to pour a little bit of water for you.

Between 2010 and 2015, 11 shuanggui detainees died in custody, including one who died during CCDI interrogation, the HRW report notes, citing media reports. Official announcements claimed that they died from natural causes, suicide, or in one case, an “accident” of unspecified reason.

In theory, shuanggui is meant to be an internal interrogative mechanism for violations of party discipline. In reality, procurators extract confessions during shuanggui and then use them in formal legal proceedings, flouting the procedural protections ordinarily available to criminal suspects.

Because shuanggui is not a legal process, evidence or statements obtained during the procedure are not admissible in court. But procurators usually tell detainees to repeat what they said during shuanggui, former detainees and lawyers told HRW.

“The CDI officers, when handing me over to them [procurators], told me to repeat what I’d said during shuanggui. They warned me, ‘If you recant your testimony we’ll bring you back,’” said one former detainee.

“Eradicating corruption won’t be possible so long as the shuanggui system exists,” said Sophie Richardson, China director at HRW, in a statement. “Everyday this system threatens the lives of party members and underscores the abuses inherent in President Xi’s anti-corruption campaign.”