It’s way too simplistic to call Italy’s “no” vote a populist victory

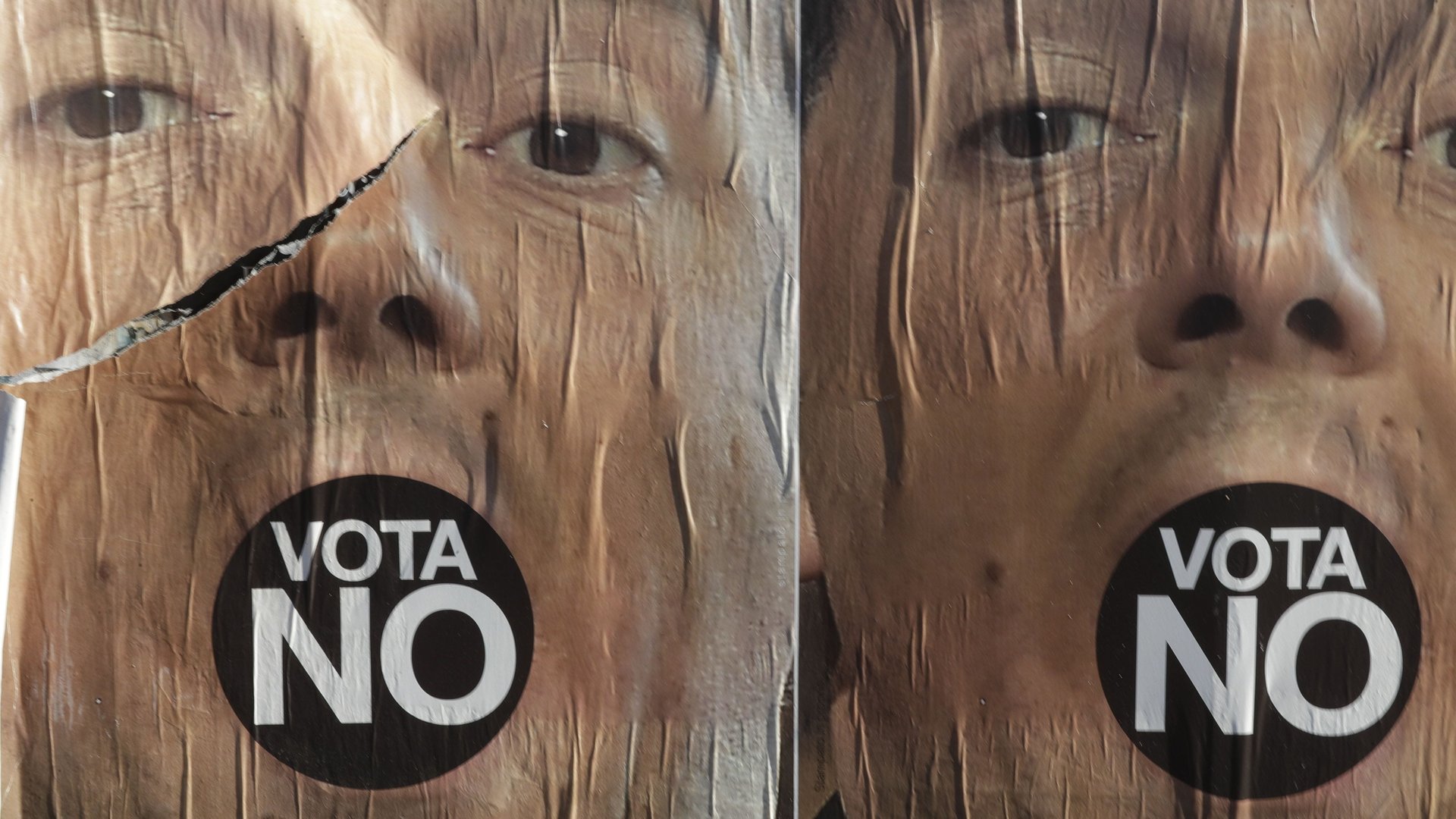

It’s tempting to view the results of Italy’s referendum this weekend as a populist victory in the same vein as Brexit or the rise of Donald Trump. With over 59% of voters rejecting the constitutional reforms promoted by Italian prime minister Matteo Renzi, who had agreed to resign in the event of a “no” vote, it’s certainly some sort of uprising. But was it a populist one?

It’s tempting to view the results of Italy’s referendum this weekend as a populist victory in the same vein as Brexit or the rise of Donald Trump. With over 59% of voters rejecting the constitutional reforms promoted by Italian prime minister Matteo Renzi, who had agreed to resign in the event of a “no” vote, it’s certainly some sort of uprising. But was it a populist one?

Arguably the outcome fits a populist narrative. Europe’s biggest populist party, the Movimento Cinque Stelle (Five Star Movement), was quick to call its voters to a “no” vote—as was the xenophobic Lega Nord (Northern League).

But while the leaders of those parties are celebrating the victory as their own, they only achieved it thanks to other voters who would not go their way in a general election: namely, those who didn’t care for the proposed reforms, or even for their government, but would still support a Democratic Party-led government and vote center-left, or left, in the next elections.

Voters who chose “no” did so for a range of reasons. Some rejected the proposed reforms because they disagreed with them, perhaps because of the dramatic colors in which their leaders painted the constitutional changes. Arguably many more—particularly voters of right wing parties and of the Northern League—voted merely against the government.

Still others used this vote to express their frustration over things which Renzi’s government cannot necessarily be blamed for after just two years in power. This was the youth vote, heavily influenced by economic hardship. Ten percent of Italians under 34 live below the poverty line; unemployed and underemployment are widespread. When these voters voted, they mainly voted “no”—especially in southern regions, which feel forgotten by this government (and many that preceded it); in some of those regions, the “no” side reached 70% of the votes.

But, many of them remain disenfranchised voters (link in Italian)—the higher the unemployment, for instance, the lower the turnout. If the US election has any lesson to teach, these are the votes that are more at risk to be gained by populist forces, so they are the ones that need to be won in the next election.

Those who voted “yes” in the referendum also had a range of reasons. Some specifically wanted the proposed constitutional change, which would have centralized decision-making power with the lower house of parliament. Some wanted to preserve the Partito Democratico (Democratic Party)-led government—including typical Democratic Party supporters, or moderate conservative voters, who are also represented in the government by ministers who belong to center-right parties.

Then there were those who, like former prime minister Romano Prodi, disagreed with the constitutional reform, but voted “yes” to avoid early elections and ward off the growing populist wave that appears to be threatening many parts of the world (minus Austria).

Finally, for some, a “no” vote was another form of protection against the rise of populism. After all, Italy’s constitution was written after fascism precisely with the intent of keeping autocrats at bay—and the political deadlocks that Renzi’s reforms sought to loosen are one of the checks on a government’s power.

As things are now, many of the left-leaning voters who rejected the referendum on the merits of the proposal are expected to go back to their progressive political affiliations, which is why, even as Renzi lost this vote, the Democratic Party is the largest in Italy (link in Italian); it is actually gaining ground over the Five Star Movement, and is far ahead of the Northern League. Considering the Five Star Movement refuses working with other parties, it would need 10% more votes than it currently has to form a government—or even more than that, pending a new electoral law to be approved before the new election is called.

Will this vote give more confidence to populist forces? That’s possible; Italy’s certainly not immune to the wind that’s blowing across the west. But the path is not clear: this vote could also galvanize citizens to oppose populism, since so many cast their vote—in both camps—for fear of it.