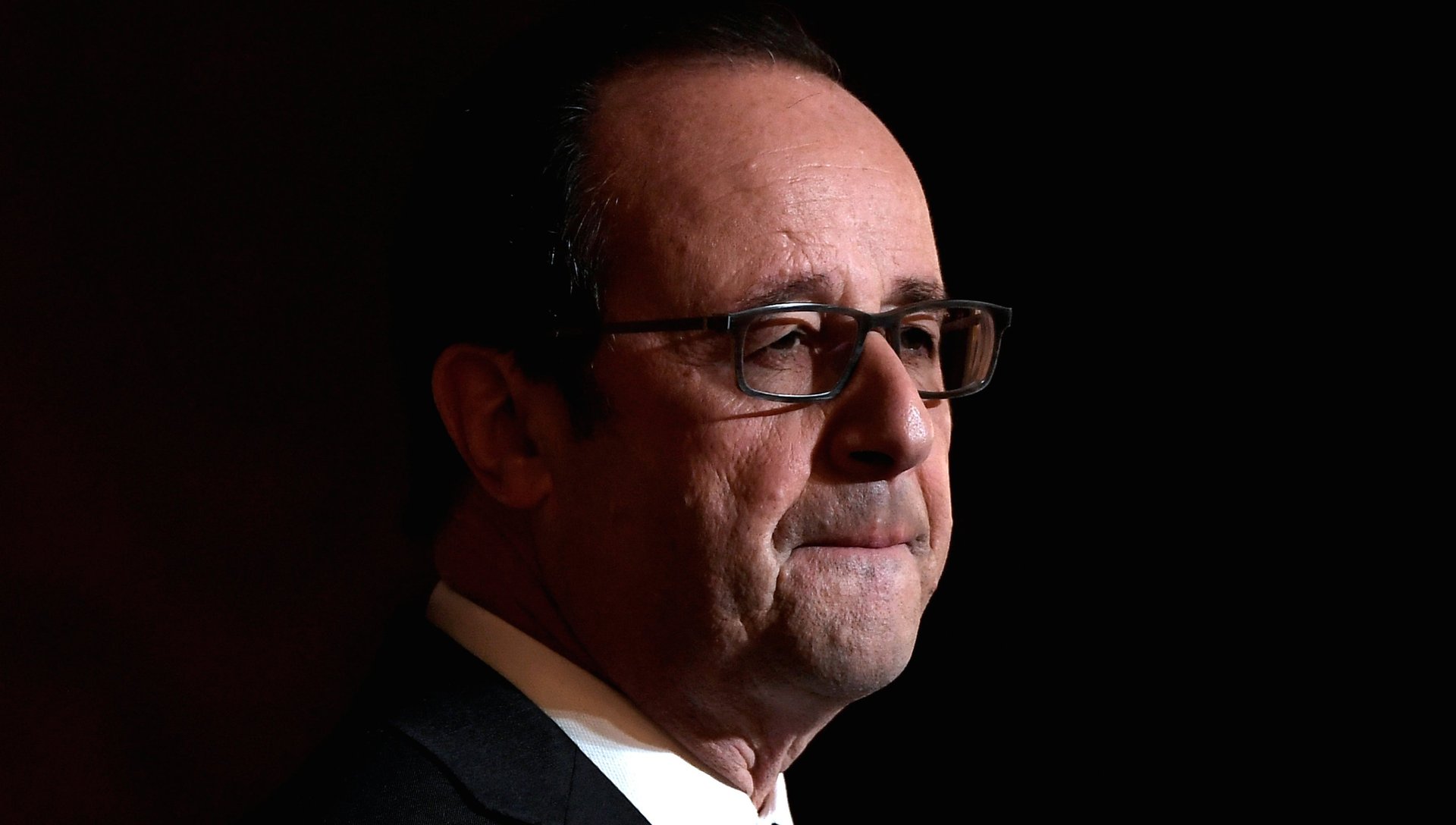

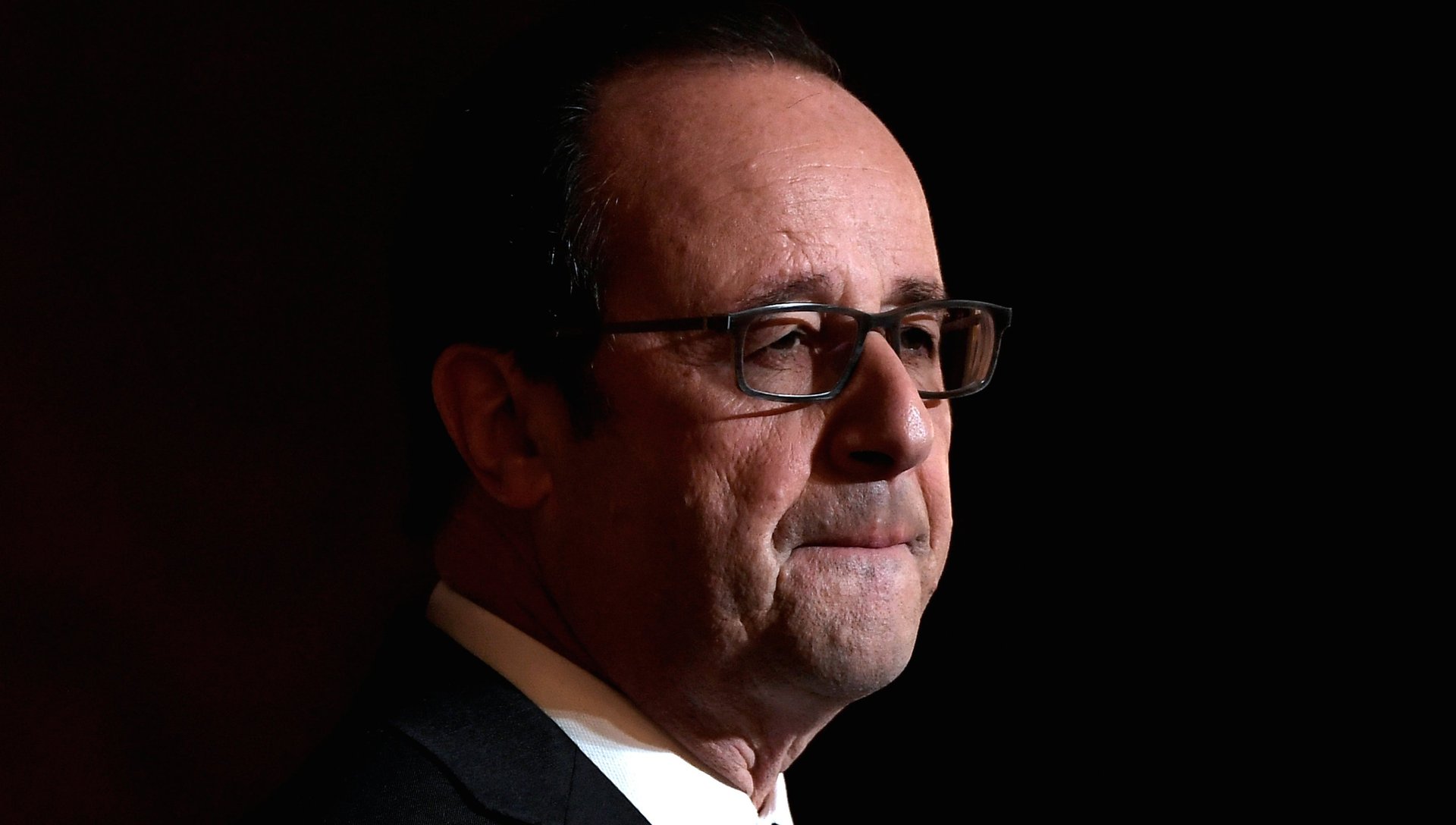

Francois Hollande’s demise proves the West’s center-left is in free fall

French president Francois Hollande announced last week that he would not seek re-election in 2017. His decision says as much about the global decline of center-left parties as it does about the personal leadership flaws of the historically unpopular politician.

French president Francois Hollande announced last week that he would not seek re-election in 2017. His decision says as much about the global decline of center-left parties as it does about the personal leadership flaws of the historically unpopular politician.

France’s Socialists, like their counterparts in Great Britain, the US, and across Europe, find themselves in disarray currently because they have failed to assuage a profound sense of economic frustration as well as what French political scientist Laurent Bouvet (link in French) calls “cultural insecurity.” Globally, the center is not holding, with a few notable exceptions, such as Austria. A disillusioned and growing minority is worried about the combination of stagnant or falling wages, outsourcing, immigration, crime, and Islamist terrorism—and afflicted by a “profound and insidious doubt about what and ‘who’ we are.”

The Hollande malaise—a problem inherited by his would-be successor Manuel Valls, who is resigning today (Dec. 6) in order to launch his presidential campaign—mirrors the plight of fractured parties of the liberal left across the west. Their leaders have been blindsided by surging nationalism and anti-establishment sentiment fueled by populists of all stripes, but especially hard-right demagogues. The National Front’s Marine Le Pen, Brexit’s Nigel Farage and, of course, Donald Trump all come immediately to mind.

The French center-left campaigned in 2012 on a class-envy platform that included a 75% tax rate for top earners that it was later forced to shelve. And while Hollande’s embattled government was able to finally pass long-overdue and vastly unpopular pro-business labor market legislation, the party’s decidedly mixed success rate on reforms highlights its inability to create a unifying narrative. Hollande needed to appeal to both the Socialists’ former working class base and to more prosperous urban liberals. He could not.

In France, the much-maligned mondialisation (globalization) is embodied by institutions like the European Union, the concept of open borders, and trade deals that have coincided with the disappearance of manufacturing jobs. The parallels between French voter backlash and America’s Trumpland are clear.

The party Hollande dominated for decades is on the edge of collapse. Prime minister Valls will attempt to rescue it from the rubble if, as expected, he becomes the Socialist candidate. But he will have to do so amid open mutiny in Le Parti Socialiste. His primary rival, Benoit Hamon, has said Valls will be unable to unite France, much like his boss. And he might be right. Despite Valls’ efforts, the center-left has found no contemporary update to the “Third Way” politics of Tony Blair and Bill Clinton, and as a result lost key swing votes. A sullen middle class, angry about dropping living standards, has become increasingly uninterested in the Socialist platform.

Meanwhile the hard-line left, represented by French anti-globalization populist Arnaud Montebourg (a weaker version of Bernie Sanders) or the more radical Jean-Luc Melenchon, believe that mainstream Socialists are cynical sell-outs.

Thumbing their noses at a demographic Hillary Clinton infamously called “the deplorables,” labor and social democrats have ossified in their privileged corner. This phenomenon was perhaps best exemplified by Hollande himself, who provided plenty of press fodder between his on-call hairdresser and parade of mistresses, one of whom said he mercilessly mocked the poor for having bad teeth.

With Hollande out of the race, France now finds itself in a tense battle for its political soul. Former economy minister Emmanuel Macron is running as an independent candidate for president in 2017 and could siphon off centrist votes in the election held in two rounds next April and May. But whoever wins the center-left’s primary contest in January—whether French secularist Valls or a wild-card possibility like the charismatic populist Montebourg—will face a mammoth task stopping Le Pen (the National Front party has no primary) from heading into the deciding ballot with plenty of momentum. At the moment, polls still predict Francois Fillon, a Catholic self-styled Thatcherite and center-right Les Republicains nominee, will become the next head of state.

How did we get to this point? The Socialist rot dates all the way back to 1981 and the election of old-style interventionist Francois Mitterrand. Mitterrand blocked wholesale reforms to the statist French economic model, and ever since unemployment has remained persistently high. Part of this has to do with the French center-left struggle to fully integrate many of France’s Muslim immigrant community, or the mass of younger job seekers.

Even though former president Jacques Chirac can be blamed for sleeping on his watch, and Nicolas Sarkozy lost his appetite for change, it was the economy—mainly recent unemployment—that did Hollande in. In neighboring Germany, where labor laws were shaken up more than a decade ago, manufacturing is booming and only 6% of the population lacks jobs. In contrast to Hollande, Angela Merkel is hoping to make a fourth run for chancellor.

Bitter societal divisions also emerged over the French president’s post-material politics of identity. Hollande never managed to build a consensus around his commitment to gay marriage. He spurred the creation of France’s first modern mass opposition movement consisting mostly of religious conservatives (mostly Catholic, but sometimes also orthodox Muslims). This group has propelled Fillon to victory in the center-right primary. The perception that Hollande was an aloof, out of touch leader from the French establishment—sound familiar, Americans?—was also a factor in his downfall.

On foreign policy, Hollande exhibited sound stewardship of a nation reeling from a wave of deadly terrorist attacks perpetuated by radicalized Muslims. However, as Islam specialist and political scientist Gilles Kepel points out in his new book La Fracture (FR), the French left’s divisions have been amplified hugely by the cascade of terrorist attacks and the ongoing state of emergency. As Hollande struggled to publicly address the issue, ideologues Kepel calls “Islamo-leftists” have deliberately exacerbated sectarian tensions in tandem with extreme right anti-Muslim xenophobes, to the Socialists’— and French society’s—detriment. Meanwhile, the left has a lot of power in France via mayors in the suburbs, where jihadism has surged. Kepel and other critics claim some mayors have even tolerated the development of extremist enclaves in an attempt to guarantee a Muslim voting bloc.

Perhaps the final straw was the publication of the book A President Shouldn’t Say That. Written by two political journalists to whom Hollande either naïvely or stupidly granted a massive amount of access, the book recorded years’ worth of contradictions and revealed the president’s deep-seated cynicism.

It is possible that prime minister Valls, with his tough on terrorism discourse and strident defense of the secular public space, could counter the law-and-order xenophobia of Le Pen, while luring some right-leaning liberals. “He is the candidate who has carried the progressive line, abandoning nothing on social protection, keep the national accounts secure, and protecting France in a time of terrorist attacks,” said the junior minister who oversees aid for terrorism victims, Juliette Meadel (link in French).

Unfortunately, a figure intimately associated with Hollande’s mandate will need something close to a miracle to succeed at the polls. Valls says he wants to unite a “independent France unyielding in its values, in the face of the China of Xi Jinping, the Russia of Vladimir Putin, the America of Donald Trump and Erdogan’s Turkey.” But most likely, it is the pro-Putin, Assad-sympathizing, EU skeptical, Trump-backer Fillon who will be moving into the presidential palace next May. Such a win, coupled with the news that Italy’s centrist prime minister Matteo Renzi is also stepping down, will deliver yet another body blow to the shrinking political center, both in France and in the West.