A state-run monopoly is killing Mexico’s chances of oil independence

Any time a single company is responsible for nearly 10% of a country’s GDP, it’s a problem. Thanks to a lack of competition, Pemex, the Mexican oil company responsible for producing all of the country’s oil, has seen production fall steadily over the past decade.

Any time a single company is responsible for nearly 10% of a country’s GDP, it’s a problem. Thanks to a lack of competition, Pemex, the Mexican oil company responsible for producing all of the country’s oil, has seen production fall steadily over the past decade.

It’s a monopoly, man

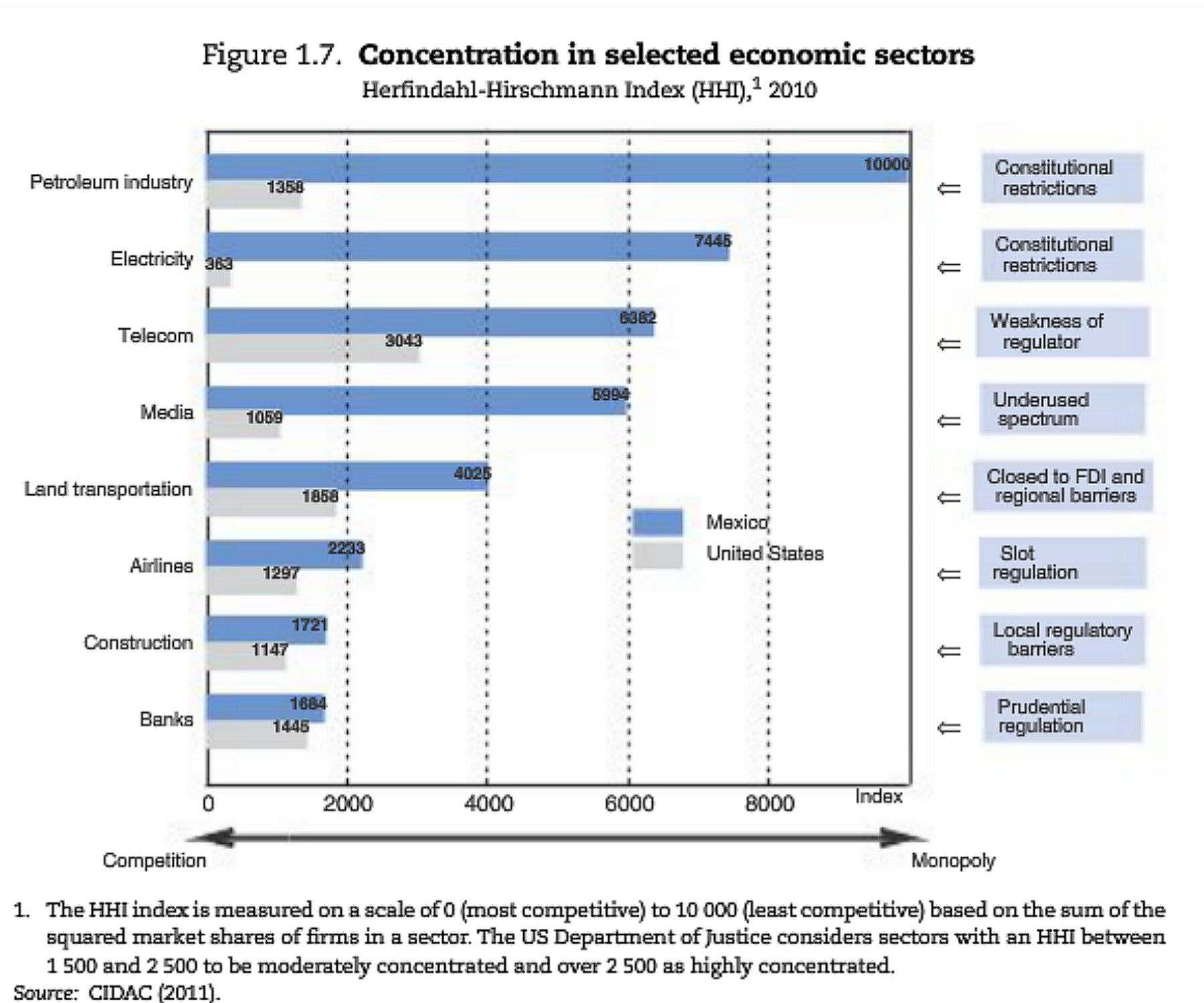

Since Pemex was nationalized 75 years ago, it has enjoyed complete reign over Mexico’s oil production. According to the Mexican constitution, Pemex has exclusive rights to: explore, exploit, refine and process crude oil and natural gas; produce basic petrochemicals and liquid petroleum gas; and carry out firsthand sales of such hydrocarbon products. Could it really be a coincidence that two of Mexico’s slowest growing sectors—oil and electricity—are also its least competitive?

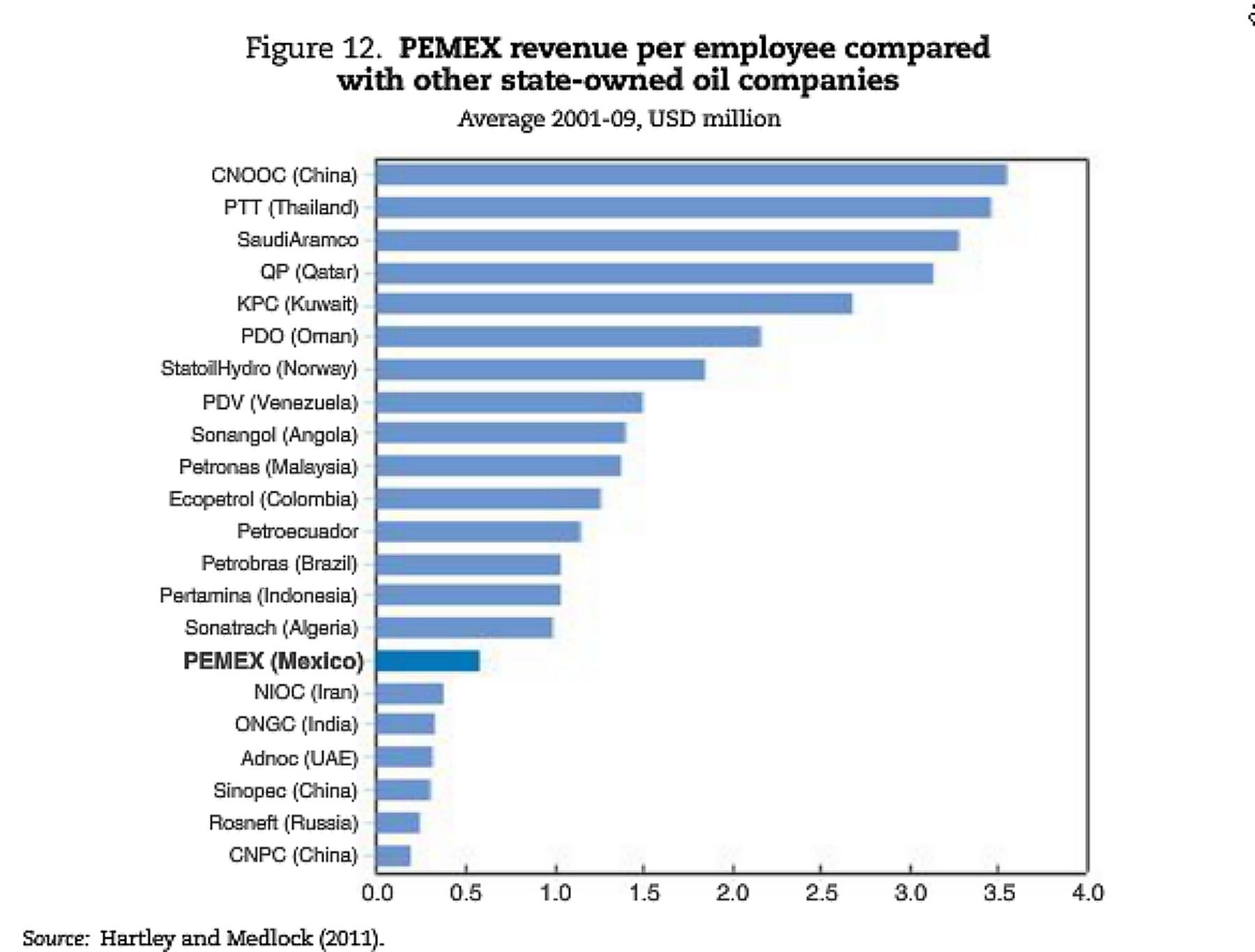

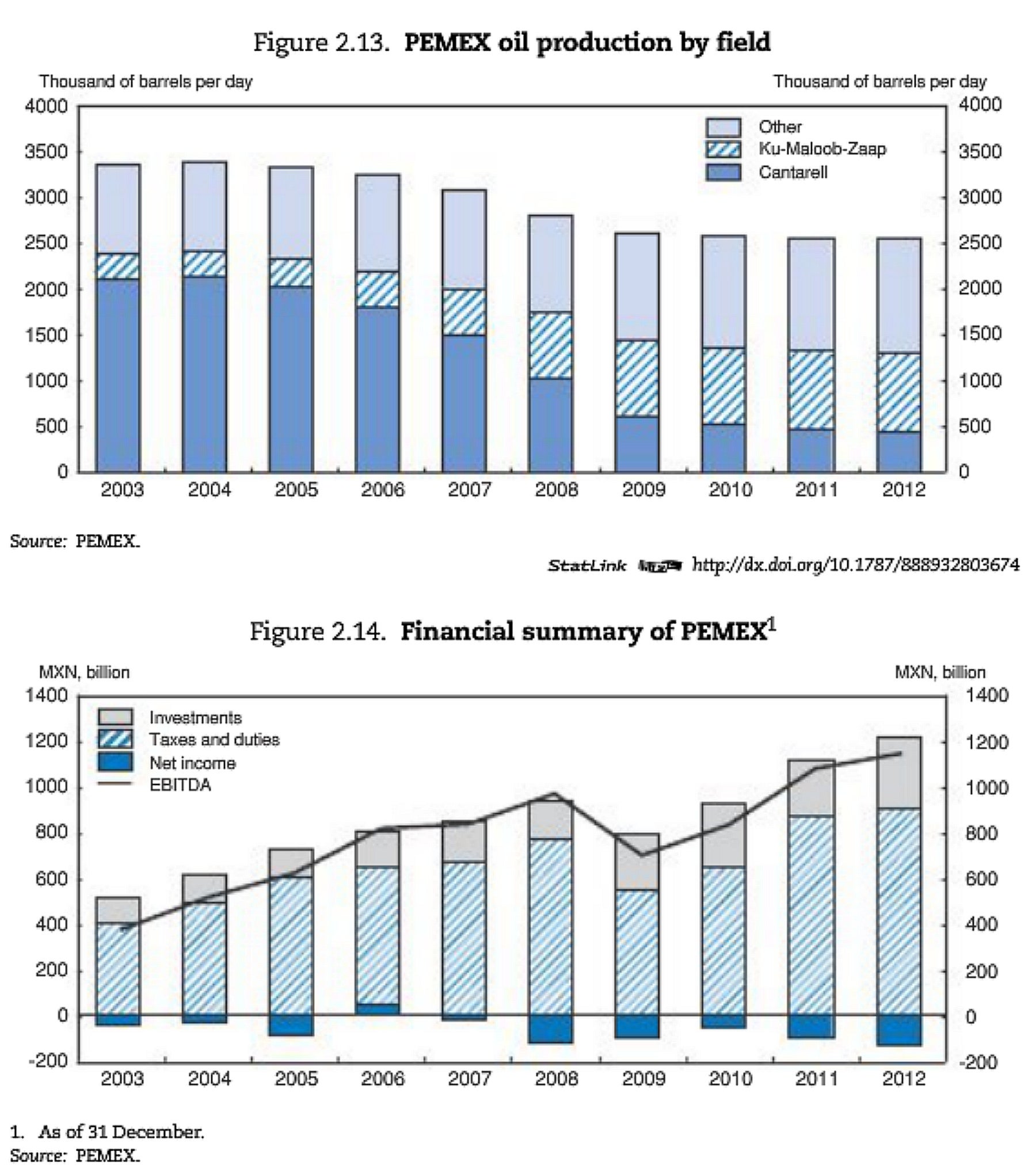

Mexico’s oil production has fallen every year since 2009. As comparatively inefficient as Pemex looks in the chart below, it’s even more inefficient today. Pemex’s oil production hit an eight-year low in 2012.

Down go production, and profits

Crude oil production has been falling in Mexico since 2004, led by tumbling output from Pemex’s largest oil field Cantarell, which is located offshore in the Bay of Campeche. As three of the company’s four main subsidiaries have made large financial losses, falling profits and productivity have followed, and are forcing the company to rely on more external borrowing to finance its investments. The company hasn’t turned a profit since 2006.

Patching up an oil dependency problem

What’s worse is the Mexican government’s unhealthy dependence on oil revenues: Pemex provides the government with roughly 40% of its budget. Opening up the oil market to private competition could mean slicing off a chunk of Mexico’s fiscal revenues.

Still, it’s a worthwhile tradeoff, especially if Pemex emerges leaner and healthier after being exposed to a bit of competition. The OECD acknowledged the same in its most recent economic survey of Mexico. “A more competitive environment for Pemex would generate adequate market incentives to improve its efficiency.”

What remains to be seen is whether president Enrique Peña Nieto is up to the task.

Earlier this year, his Institutional Revolutionary Party agreed to “end its opposition to constitutional changes that would ease state-owned Pemex’s grip on the oil industry.” It’s a promising start to solving Mexico’s imminent oil crisis. But there’s still no bill on the table that proposes a break-up of Mexico’s state-owned oil-monopoly.

Nieto doesn’t appear to be all that committed to solving his country’s oil problem. He later back-tracked on his supposed plans to privatize Pemex, saying the company “will neither be sold, nor will it be privatized, and calling it a “symbol of progress and national identity.”

Identity, perhaps. But progress? Please.