At the center of the Philippines’ battle with fake news is a pop star with a legion of Duterte fans

Manila, Philippines

Manila, Philippines

The show began like many other casino acts do. On the last Tuesday of 2016 in Resorts World Manila’s Bar 360, six girls in matching white tank tops and shorts walked up to a stage lit with strobe lights, and danced to hits including Don’t Let Me Down by The Chainsmokers. The hour-long set was standard for variety shows in the Philippines: song numbers, audience dance competitions, and sexual innuendo just mild enough to be shrugged off as cheeky. But toward the end, the performance took a turn.

For their last dance, the girls called on people in the audience to join them in a high-energy rendition of the “Duterte Dance.” Leading the group was Mocha Uson, Philippine president Rodrigo Duterte’s controversial celebrity endorser.

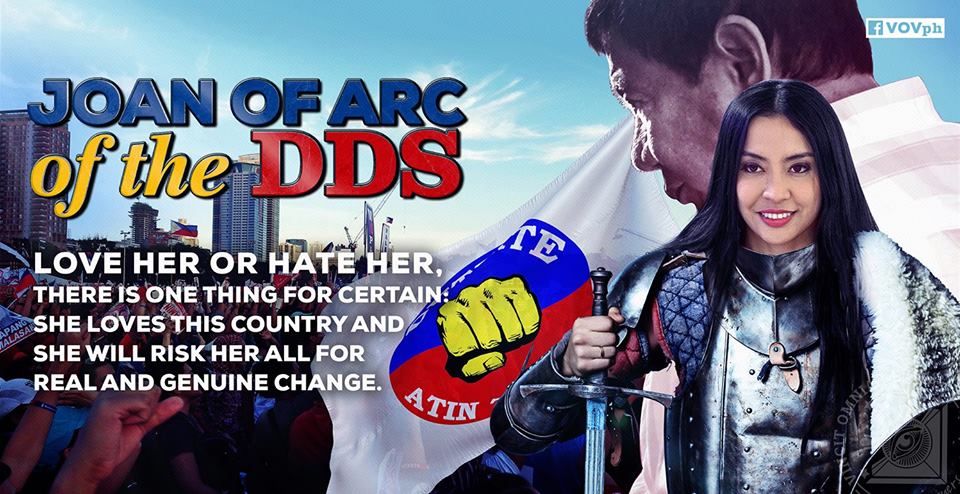

Uson is a singer turned political activist with more than 4 million likes on her Facebook page. She has been accused of spreading erroneous news and inciting online hate, but the positive reactions and comments on her posts show that tens of thousands of her followers are unfazed by this. On one hand, she is seen as a conduit for fake news and a prime example of ad hominem arguments prevalent on the internet; on the other, as the voice of a previously silent majority of Filipinos hungry for change.

The BBC recently confronted Uson about a photo she shared of a dead child’s body with the following caption: “Truly revolting – Nine-year old raped and murdered and we haven’t heard condemning this brutal act from humanrightists, bishops and ‘presstitutes’ who are derailing the government’s war against drugs and crime.” Only, the photo was taken in Brazil, not the Philippines.

Uson did not create the post—it was written by a spokesperson for Duterte’s campaign. She also told the BBC that she took down the post after learning it contained a false report, but by then, it had already been liked and shared by her followers.

Her Facebook page is but one of the many proponents of fake news, but her popularity means more than usual in the Philippines, a nation of highly active social media users. Ador R. Torneo, a political science associate professor and research fellow in De La Salle University in Manila, said that this is an effect of the millions of Filipinos living abroad and the geographical limitations of an archipelago made up of more than 7,000 islands. Filipinos turn to social media to feel connected, and part of that is following news updates, he said. But because many have limited data subscriptions that provide free Facebook access and little else, they are primed to fall victim to clickbait headlines and share posts without reading the full article.

Who is Mocha Uson?

Uson is a pop star whose claim to fame is being the leader of a provocative girl group called the Mocha Girls.

The group performed during Duterte’s national campaign tour. By the end of the election in May, Uson came out as an influential voice for Duterte, doubling the number of Facebook followers she initially had. Recently, she was also appointed a position in the government’s Movie and Television Review and Classification Board. Some questioned her rise as a government official and political commentator, but her support for Duterte is tied to a tragic past.

Her father, a provincial judge, was assassinated in an ambush shooting in 2002. “If a judge who dispenses justice could not be given protection and justice by our government, how much more for ordinary folks?” Uson said on Facebook. She ended the post with an endorsement for Duterte, saying that an iron hand for criminals is what the country needed.

Some of the issues she championed in the past are also in line with Duterte’s policies. Uson promoted the Reproductive Health law, was a proponent for sex education, and once challenged the Catholic Church to excommunicate her for her stance. She also identifies as bisexual; out of the five presidential candidates, Duterte was one of only two in favor of same-sex marriage.

But Uson the blogger is a different beast altogether. Her page is less about her and more about the community she has brought together, an idea that she has acknowledged.

“This is what other pages/media do not understand, that the Mocha Uson Blog is not me. Just like what others say, I am just a megaphone and you are the voice. I simply shout what you are saying,” Uson said in a comment.

Through her posts, she sparks conversations on topics like vice president Leni Robredo and the controversial burial of former dictator Ferdinand Marcos. But the real effect comes from the fire she helps ignite in the comments section. Uson sets the tone, but it’s her followers who bring the conversation from social media to the real world.

Not a journalist

Uson’s popularity earned her a weekly column on the national broadsheet, the Philippine Star, yet she still describes herself as “Not a journalist just an ordinary Filipino” on her Facebook profile. In fact, she regularly calls out the media for being biased, accusing them of being “presstitutes” paid by the opposing Liberal Party, of which Duterte’s opponent, Mar Roxas, is a member. To many Filipinos, Roxas, the Liberal Party, and, by association, the media, represent out-of-touch elites.

Uson, in contrast, is considered a “barometer of public sentiment,” according to Thinking Pinoy, an anonymous blogger who is pro-Duterte.

“The media now is very questionable because it’s all about profit,” said Liezl Muego, a 32-year-old Filipino domestic helper in Hong Kong. “As long as someone pays them, they’ll report it right?” Muego has been working in Hong Kong for eight years but is originally from Davao, the city where Duterte hails from. She gets her news mostly from Facebook and said she prefers bloggers over mainstream media. “Mocha is more credible now.”

Torneo at De La Salle University said the dislike for traditional media is a backlash against negative articles written about Duterte during the campaign, including stories about his profane comments to the pope during the pontiff’s visit to the Philippines, and his joking about a rape victim. “Deliberate or not, it has been part of the Duterte campaign to discredit mainstream media,” Torneo said.

Some, however, see Uson’s branding of Duterte as an everyman as a way to wash her hands of the responsibility that comes with social media popularity.

“I think it’s a cop out,” said Aura Soriano, a 24-year-old architect from Manila. Soriano supported Duterte in the early stages of his campaign but ultimately decided not to vote for him a week before election day. She said of Uson, “She knows that she’s making people angry and fight each other and why would you do that? There’s no greater purpose to it. It doesn’t help our country, it doesn’t help our countrymen.”

Fresh from the content farm

According to Ann Choy, a research assistant at the University of Hong Kong’s Cyber News Verification lab, most if not all the stories in Uson’s timeline are from content farming websites that poach stories from other sites and re-publish them with a sensationalized title. These websites have no distinguishable owner, use default templates from blog hosting websites, are sometimes in support of an agenda, and simply link to each other instead of verifiable sources.

In November, Uson posted a photo of the magazine covers Robredo appeared in, insinuating that the vice president wasn’t doing her job and calling on her to “stop campaigning for 2022,” the year of the next presidential election. But of the six covers Uson posted, only two came out after Robredo became vice president, the same number of covers Duterte appeared in after winning.

In October, a petition to suspend Uson’s Facebook page received more than 33,000 signatures, but Uson’s supporters proved to be stronger. Not only did the Mocha Uson Blog remain active, but the profile of the man who started the petition was reportedly suspended after multiple reports were made against him.

This kind of activism is made possible by groups of Duterte supporters who use their social media and IT expertise against those who don’t agree with their views. Colleen Navarro, a 36-year-old supporter of Roxas and Robredo who works as a personal assistant working in Hong Kong, said her Facebook account was hacked three times, each time from an IP address in Russia. The alienation that came with her political choices extended to her real life relationships, too, and caused a rift between her and her friends. “You’ve been together for how many years, for more than a decade,” said Navarro. ”And just because I am now pro-Roxas, they’ll call me stupid, they’ll call me crazy.”

Uson did not reply to multiple interview requests from Quartz. Her manager, Byron Cristobal, initially replied through text message but said that Uson is too busy to accommodate an interview. The blogger behind Thinking Pinoy agreed to be interviewed but eventually blocked Quartz from Facebook and declined phone calls.

The battle against fake news

The Philippines’ Cybercrime Prevention Act was signed into law in 2012 and penalizes online forms of libel. It holds the author of the post liable, but not those who received or reacted to the post.

However, that doesn’t mean those who share these articles are in the clear. “Even if you are not the author but having shared and proliferate the erroneous article, the offended party can file a complaint about the erroneous post,” said Phydias Ramos, a partner at Manila-based law firm Pamaran Ramos and Partners Law Offices.

Another weapon against fake news is news literacy education. The University of the Philippines aims to do this through UPTV, an online channel it launched in November. It will share videos that teach people how to distinguish credible articles from fake ones starting this year.

But not everyone wants to seek out information about news literacy. To millions of Uson’s followers, something that she shares has her stamp of approval, and that is enough verification for them.