For almost a year, Tanzanian officials had been in a bitter $600 million dispute with Dangote Cement over investment incentives related to a new cement plant in Mtwara, southern Tanzania. The Nigerian company had claimed the government was reneging on promises made by the previous administration of president Jakaya Kikwete, who left office thirteen months ago.

The cement plant launched last year and was flourishing until John Magufuli became president. In the last 12 months, new regulatory challenges undermined operations to such a degree, that the company suspended production last month. It caused an uproar in Tanzania. And Magufuli had to get directly involved and eventually struck a last-minute deal with Dangote on Saturday (Dec. 10) to keep the factory in the country and save thousands of jobs that were at risk if it closed.

Put another way, Dangote called the government’s bluff—and won.

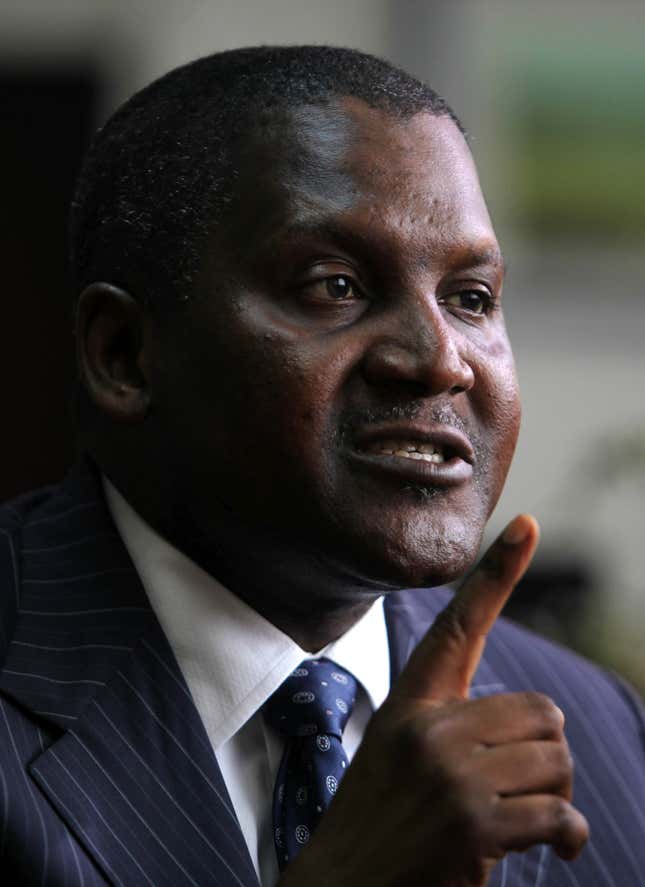

But this isn’t about Dangote, Africa’s richest man and a powerful figure on the continent who can probably get any president on a cellphone if he needs to. The dispute, instead, had troubling implications for watching investors who might have been thinking of coming to Tanzania or deepening existing investments there. Analysts say it has already noticeably hurt the country’s reputation as an investment destination. They think it looks like east Africa’s second largest economy is not only a difficult environment for the private sector, but that the new administration is hostile to business.

Between politics and a hard place

“In the long-run, the fact that we got to this point, paints an unfavorable and unpredictable outlook for investors looking at the Tanzanian market,” says Ahmed Salim, an analyst at Teneo Intelligence. Relations between business and the government are already strained.

In May, the American energy company Symbion threatened to sue the government for breach of contract, after the state-owned electricity supplier abruptly terminated an agreement with the firm.

A month later, the finance minister introduced a bill that Magufuli later signed, compelling mobile phone companies to list 25% of their businesses on the Dar es Salaam Stock Exchange (DSE), despite concerns that the market was not mature enough to meet the liquidity demands of such an offering.

Last month, investors threatened to withdraw their investments from the country citing a strict new tax regime.

There’s currently a power struggle in government between the Tanzania Investment Centre (TIC), an agency tasked with incentivizing the private sector, and the Revenue Authority which is ramping up revenue collection and winning.

“If you’re told one day, out of the blue, that you’re no longer exempt from VAT, not only does it throw a spanner in your current business, it also affects your confidence about your future investment decisions,” Anna Rabin, a senior analyst at consulting firm africapractice, told Quartz.

As it is, Tanzania currently ranks 132 out of 190 when it comes to ease of doing business. Its obsession with raising revenue at the expense of business environment will not improve this position, analysts say.

A former socialist state, where deep suspicion of private enterprise still lingers, Tanzania worked hard in the last decade to attract investors, such as Dangote, to come do business in east Africa’s second largest economy. But there are now fears that the work done to open things up will bet set back.

The Kikwete years saw the reality of a difficult business environment mitigated by government support and incentives to the private sector. This is no longer the case with Magufuli, analysts say. While the tough investment climate remains, those incentives have now disappeared.

“Investors feel that the want for upfront revenue collection is to the detriment of the potential to secure future investments,” Rabin said.

By over-taxing business, the government risks suffocating the economy, starving it of liquidity, with dire implications for jobs and future revenues for the country.

The Dangote situation is a case in point. If the government continued to push the plant to pay more taxes without any incentives and the plant had shut down, the consequences would have been dire. Since the company halted production, the price of cement has gone up, increasing costs in the construction sector. If operations failed to resume, close to 10,000 jobs would’ve been affected, according to some estimates.

Broken promises

Magufuli, nicknamed “the Bulldozer”, has garnered pan-African praise (paywall) for clamping down on corruption and holding the private sector accountable. But in taking on Dangote, a rare homegrown African multinational, which creates thousands of jobs wherever it goes, the Magufuli administration may have shot itself in the foot.

The Dangote plant validated former president Kikwete’s use of incentives such as tax breaks and cheap energy costs, to attract high level investment to the country. This tactic had made Tanzania one of the most attractive for foreign direct investment in East Africa.

Fault-lines between the company and the government began to appear soon after the Magufuli administration was ushered in, in Nov. 2015. The Kikwete government promise of low-cost gas to power the plant did not materialize. This was a blow to Dangote, which had placed its operations in Mtwara, specifically, to access cheap natural gas mined in the region.

“Before Kikwete left, the gas issue hadn’t been resolved but there were promises made that Dangote would get gas at a cheaper price,” a person familiar with the company’s business in Tanzania told Quartz.

So Dangote decided to import coal from South Africa to fuel the plant. But Magufuli’s government demanded import duty on the coal, and eventually banned imports, trying to force the company to use more expensive, low quality local coal.

Yet, the ministry was unbowed. “We don’t want to hear that the price of imported coal from South Africa is cheaper than the price of coal from Mchuchuma to Mtwara,” Medard Kalemani, deputy minister for energy and minerals, said.

This forced Dangote to rely on generators which sent operational costs soaring to $2.5 million a month since August, the source told Quartz.

This was the last straw for Dangote and the plant stopped operations in November for what the CEO said were technical issues.

Magufuli’s personal intervention has created some optimism that it may signal a new phase in the government’s engagement with investors and the private sector in general.

But the president cannot insert himself into every business negotiation. Reforms are needed to create conditions that are both favorable to the private sector and Tanzanians as a whole.

“Instead of fixing the laws, people are trying to run a new, modern economy with outdated, flawed laws,” the person familiar with Dangote’s Tanzanian business said.

And things will only improve if Magufuli demonstrates the political will to institute such a mind change.