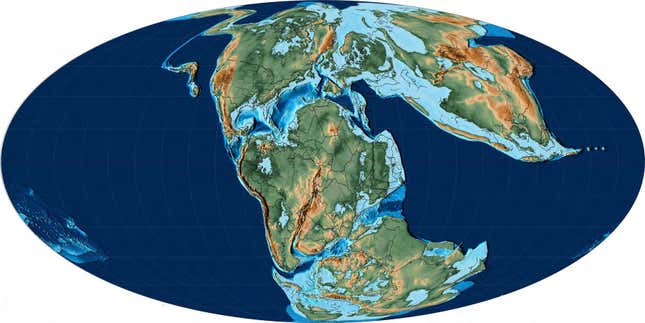

Even though it was still part of the giant land mass of Gondwana, the outlines of what came to be Greater India finally began to be discernible about 145 million years ago. The mountain range that would later split to become the Western Ghats already marked the boundary with Madagascar to the west. In the north lay the craggy Aravallis that extended into a shallow sea to the north and west. In the east, a rift valley was beginning to form between India and Antarctica which would eventually become the eastern coastline of India. This rift valley between Greater India and Antarctica and Australia continued to widen until total separation of the two land masses happened around 122 million years ago. This was roughly when all the continents began to move towards their present positions.

Greater India had its own spectacular array of Cretaceous dinosaurs. The best and richest source of dinosaur fossils from this period is the fossil-rich sedimentary layer along the Narmada river, known as the Lameta formation, named after a bathing ghat which lies on the outskirts of Jabalpur, en route to the famous marble cliffs of Bhedaghat where the river drops as the Dhuandhaar Falls.

The Narmada originates in Amarkantak Hills in Anuppur district of Madhya Pradesh, and travels through Maharashtra and Gujarat, covering more than 1,300 kilometres during its journey. For about 200 kilometres on the banks of the Narmada flowing through Jabalpur are marble and dolomitic cliffs overlain with sedimentary rocks. These preserve fantastic fossils from this period. If you want to go looking for fossils in this area, a starting point would be the hilly region around Jabalpur. This area was once flanked by the Narmada seaway to the west, with other rivers originating in the Vindhyas flowing around it. The ebb and flow of river water deposited copious quantities of silt and sediments layer upon layer, preserving the fossils within them.

It is, therefore, not surprising that the first dinosaur to be discovered in India, a sauropod called Titanosaurus indicus, was found in a massive sediment horizon in a place called Bara (meaning big) Simla Hill near the army cantonment in Jabalpur. Titanosaurs (or giant reptile) were the giant herbivores of the Cretaceous period. Fossils of bones and eggs of titanosaurs and some other dinosaurs have been found extensively along the Narmada.

Jabalpur cantonment has a second hill close to the Bara Simla Hill called the Chhota (meaning small) Simla Hill where broken bone fragments can be found as you ascend. At the base of the hill, within the boundary walls of the Gun Carriage Factory in Jabalpur, one of India’s largest artillery and armaments factories, is a temple complex called the Pat Baba Mandir dedicated to Hanuman and other Hindu deities.

The temples’ precinct offered protection to the bones, eggs, and nests that were discovered here because generations of priests and devotees believed that the eggs were signs of Shiva that appeared after he slayed the asuras (demons) who terrorised sages in this forest. Tragically, during a renovation in 2011, many nests and eggs were damaged and lost, and today very few fossils remain in the possession of the temples’ priests.

The seaways that cut through the middle of the Indian land mass were shallow and dotted with islands, and it was probably easy for large migratory dinosaurs like Titanosaurus to wade across these waterbodies. At least seven different species of these gentle, plant-eating giants from the Cretaceous period have been identified in India alone.

Titanosaurus varied greatly in size and external appearance; there was even a Titanosaurus that was armoured, with plates as bony extensions emerging from its skin. The bones of Titanosaurus suggest that they were perhaps related to a South American dinosaur called Saltasaurus. When Barapasaurus and Kotasaurus became extinct, Titanosaurus dominated as the top browser and is the largest known dinosaur of the Cretaceous period in India.

Over 25 metres long and about 12 metres tall, Titanosaurus was small in comparison to Barapasaurus, but still as tall as a four-storeyed building. For such an enormous creature, its teeth were extremely small and thin and palæontologists believe they were perhaps used only for stripping leaves and shoots and not for grinding or chewing. That work may have been performed by the gastroliths (stomach stones) in its digestive tract. Like many other sauropods, Titanosaurus also had a large thumb-claw that may have helped their young ones defend themselves against predators.

But the biggest weapon these dinosaurs had was their whip-like tail that was capable of stunning any would-be predator. Studies done on trackways and footprints of large sauropod herds in Argentina and the US show that walking in packs with the young in the centre was probably a defensive tactic Titanosaurus employed against predators. Despite being widely found, there is no assembled skeleton or even an authentic illustration of any Titanosaurus from India.

While the herbivorous Titanosaurus lorded over low tropical jungles, small carnivorous dinosaurs like Indosaurus (meaning “Indian lizard”) and land crocodiles like Laevisuchus (meaning “light crocodile”) lived in dense forests along the Narmada. Another menacing predator from this period was Indosuchus, which had a skull that measured almost one metre, and razor-sharp front teeth that were 10 centimetres long. Indosuchus hunted in packs to challenge larger predators. Its fossils have been found at many other sites along the Narmada and a few vertebrae have been found in the limestone beds of Ariyalur district in Tamil Nadu, too.

About 90 kilometres east of Ahmedabad and 70 kilometres north of Vadodara, close to the end of the Narmada’s journey, in the village of Raiholi in Gujarat’s Kheda district, lies an extraordinary fossil graveyard. Raiholi features prominently on the world’s palaeontological map because it is one of the best places to see dinosaur nests and eggs. Interestingly, its discovery was almost accidental. In fact, dinosaur eggs appeared rather late—a little over three decades ago—on India’s palaeontological scene.

In October 1982, professor Ashok Sahni, an incurably curious and widely respected palæontologist, was attending a seminar at the Physical Research Laboratory in Ahmedabad when a young officer of the Geological Survey of India (GSI), Dhananjay Mohabey, asked him about a round rock, about the size of a coconut. Mohabey worked with the GSI’s Nagpur office and, while on a survey of the Gujarat region, had heard of the frequent discovery of “cannonballs” during blasting operations at the ACC Cement factory at Balasinor, not far from Raiholi. The mine managers often decorated their shelves with these so-called cannonballs and used them to line garden paths leading to their site office. Professor Sahni analysed the shell cover of the “cannonball” Mohabey presented to him and found that it was the egg of a dinosaur!

After this, reports of the discovery of dinosaur eggs began pouring in from other sites around Raiholi and new locations in Gujarat, western Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra by GSI officers and other researchers. However, Raiholi remains the largest nesting ground of dinosaurs discovered in India, perhaps even in the world. Many nests are clustered together here in close proximity, suggesting that these were communal breeding grounds like the nesting colonies of penguins. The nests were made like hollows in the mud or sand and were lined with vegetation. In each nest, the eggs were laid or arranged in a neat pattern so they would not roll around or bump into each other.

Tragically, as soon as news of this discovery spread, these sites were looted. Even today, if you stop at a tea stall near Raiholi, you might be approached by locals offering to sell you dinosaur eggs. The Gujarat government has set up a conservation site in Raiholi and has made it a recreational park with two massive dinosaur replicas at the entrance to welcome visitors. But a lot of damage has been done to the site by vandals and today only the outlines of eggs within nests can be seen here.

Soon after the Raiholi discovery, a second site rich in dinosaur bones was discovered close by, across the state highway, that came to be known as “Temple Hill.” Fossil bones are so common here they can be gouged out from rocks with a pen knife. In one particular part of Temple Hill, in a patch of ground only seven square metres in size, several bones were found which gained attention out of proportion to their size.

Suresh Srivastava, a GSI geologist based out of Jaipur, worked diligently at the Temple Hill site between 1982 and 1984, painstakingly unearthing bones and carefully noting the position of each one. He found a single braincase located about 3.5 metres away from the backbones. Because the relative sizes of the bones matched, the bones were thought to belong to a single individual. Close to this grave was another set of long bones many of which were broken and which, on closer analysis, were identified as those belonging to several individual sauropods.

Srivastava worked on the bones for several years, cleaning them of extraneous mud and accretions and placing them carefully in cartons. In 1994, Paul Sereno from Chicago’s Fields Museum and Jeff Wilson from the University of Michigan were visiting India and met Suresh Srivastava in the GSI office. When Srivastava opened the Temple Hill cartons and showed them the bones of the skull, the two American palæontologists quickly realised that this was no ordinary dinosaur.

Wilson, a PhD student then, carefully pieced together the bones under the expert supervision of Sereno and Ashok Sahni. It took them eight months to assemble the skull bones and reveal the apex carnivore of the Cretaceous period in India. They named it Rajasaurus narmadensis (meaning “king lizard of the Narmada”). From the size of its skull, they estimated that this predator was about 10 metres in length. Further analysis suggested that it had a robust build and a very strong skull and neck. Although it was smaller than Tyrannosaurus rex, Rajasaurus was perhaps more ferocious because it had the framework for greater agility and a stronger bite. It was perhaps a bit like the compactly built but superbly effective boxer Mike Tyson!

Rajasaurus is thought to be closely related to Majungatholus, a dinosaur from Madagascar, because their skulls and teeth were similarly shaped and their general appearance probably matched. This, of course, is not surprising, because you will remember that Madagascar at that time was still joined at the hip with western India!

Excerpted with permission from Indica: A Deep Natural History of the Indian Subcontinent, Pranay Lal, Allen Lane. This post first appeared on Scroll.in. We welcome your comments at ideas.india@qz.com.