The economics of being Santa

If you’ve celebrated more than 30 Christmases in your life, your memory of a visit to see Santa would probably be considered quaint by today’s standards.

If you’ve celebrated more than 30 Christmases in your life, your memory of a visit to see Santa would probably be considered quaint by today’s standards.

Santa was at the local mall, but he was visible from the end of the line, one that couldn’t be bypassed for the price of an online reservation. There was nothing to do in the queue but practice reciting your list, which was scribbled on a piece of paper. When you finally reached Mr. Claus, he gave you as much time as you needed.

Children haven’t changed, but the times have. Like so many other businesses, the Santa game has grown more pressurized and intense, more stratified, and increasingly aided by digital tools. At Toys R’ Us, for instance, the kids who see an in-store Santa can also walk the aisles with a handheld barcode scanner, pointing at the stuff they like and creating their digital wish list, the way engaged couples build a wedding registry.

At its heart, the job of playing Santa is still about personifying one of history’s most enduring, beloved mythical characters. But it’s also just another gig in the service economy. Here’s what we know about the Santa business now.

Santa is expected to maintain a high throughput of visitors

Christmas has “an inordinately significant role in the legitimation and continued functioning of free-markets,” says Philip Hancock, a professor of management at Essex Business School. This might sound farfetched, but as he points out in a recently published essay in Academy of Management, the holiday accounts for billions in production and consumption annually, supports global supply chains, and millions of seasonal jobs.

In the US alone, the retail sector is planning to add 700,000 seasonal jobs this year, and UPS and FedEx hired tens of thousands of short-term employees, while shoppers are expected to spend nearly $700 billion in the last two months of the year.

However, while Santa, the myth, might be the ambassador for the spending fest, Santa, the man, makes a respectable income. Mall Santas in the US earn between $35 and $50 per hour, and can take home $10,000- $20,000 per season. For these wages, they are expected to uphold a particular brand aesthetic, says Hancock, even when they’re stuffed into a poorly ventilated “grotto,” the UK version of Santa’s fabricated small home.

By far the leading complaint Santas shared with Hancock was the pressure to increase visitor throughput, while still making each child feel special and attended to.

For many mall Santas, the usually much younger and often female elves have become taskmasters, cheerfully and relentlessly reminding Santa to “hurry it up” because the line must keep moving.

Mark Brenneman, an independent Santa who also runs the Santa and Company talent agency in Phoenix, says that mall Santas are typically allotted one to three minutes per child, which tracks closely with estimates from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Like the owners of a busy restaurant, the production and photography companies earn more with high turnover. When mall Santas tire of that racket, they seek out small employers like him, instead, he says.

The 1% of Santas earn $1,000 per day for attending parties thrown by Russian oligarchs, or celebrities

Just like any labor market, Santas are hired across a spectrum of price points. More comfortable working conditions—with better change rooms, slightly higher wages, or more air to breathe—exist at higher-end establishments, like Harrod’s in London or Macy’s in New York.

Independent Santas, who sometimes work with a talent agency or advertise their services on LinkedIn, can make the highest income and attend the most posh events. Hancock met Santas who recalled fancy corporate bank parties (child-free events when adults sometimes got drunk and inappropriate), and chauffeur-driven rides to the estates of Russian oligarchs. These Santas command higher hourly rates than a mall Santa though they are also offered fewer hours. Brenneman, for instance, pays his talent $75 to $150 per hour according to rank (Santa is the chief commander, reindeers are the foot soldiers), but agencies in big cities pay up to $350 an hour.

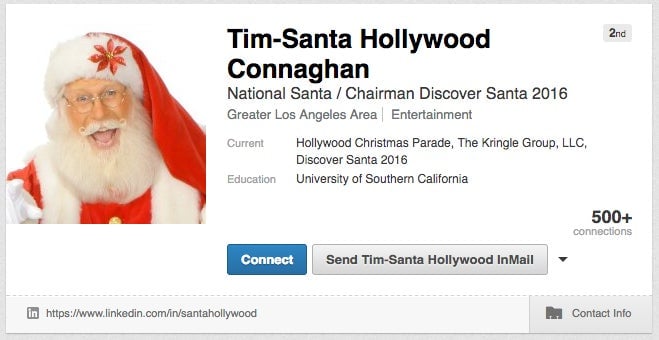

Tim Connaghan, aka Santa Hollywood, a former journalist and fundraiser who has also started Schools4Santa, works this higher end of the market. He says he decided to become a Santa watching the 1980s TV show, The Lifestyles of the Rich Famous, which once featured a Los Angeles-based Santa who earned $1,000 per day. Connaghan confirms that he now earns that much, too— when not volunteering at charity events like the Hollywood Christmas Parade— and the Santa who had inspired him is now an annual feature at the Kardashian Christmas party.

A select few mall Santas in the US are also sometimes treated like celebrities. If his customer service is highly rated and the word of mouth (or social media) is positive, the photography companies who produce Santa Villages—the Big Three who control the market are WorldWide Photography, Noerr Programs and Cherry Hill Photo—will do what it takes to retain that star employee.

Denise Conroy, CEO of Iconic Group, which owns Worldwide, says her company will fly a top Santa across the country, put him up in a hotel for the duration of the season, and pay him up to triple the going rate. “They really are like actors,” says Conroy, who previously worked in marketing for HGTV. “The best are the ones who are confident enough to have their own schtick.”

Santa knows who’s been nice, because parents give him that resale data

Since the 1890s, when the first department stores in London and the US began using Santa as lure to increase footfall in their shops, the two cultures have diverged slightly in their approach to monetizing Christmas Villages.

In the US, visiting Santa has always been free, though parents feel obliged to buy the official photo keepsakes, currently priced between $20 to $99. (Malls usually get a cut of the revenue, which can amount to $1 million or more.) In the UK, however, Santa’s guests are charged an average of £8 ( $10) per head, or up to £45 ($55) at speciality shops like Hamleys, and only more recently have begun to charge for photography.

The holiday displays that house a jolly Saint Nick have also become expensive, elaborate affairs, packed with distractions. “Recognizing that the parents can’t wait in line without being bored, the whole queue has become an experience, with cinemas, talking mailboxes, and animatronics,” says Hancock.

In the past two years, select US malls across the country have also begun hosting small Disneyesque attractions like the Dreamworks-designed “Adventure to Santa.” Inside a 2,000-square-foot cottage that sits in a mall court, families board a sleigh for a simulated flight to the North Pole where they “surprise” Santa in his study. What this means is that Santa is not visible from the outside, and the six- to seven-minute journey costs $40 to $75 per family. That angered parents in Philadelphia last year, when the minimum ticket price was a little lower at $35. Complaining that the cost was unfair to low-income families, the customers convinced the owners of Cherry Hill mall to abolish the ticket price entirely.

Parents are asked to pre-book their adventure to lock down their time in the simulator, but even no-frills Santa Villages now often offer online bookings. This has created a new line of revenue for the photography companies, that turn the collected information—names, email addresses, names and ages of children—into sellable data. According to Hancock, data is now the hot commodity for Santa production companies. WorldWide’s Conroy says she knows that’s true among competitors (who did not respond to Quartz’s request for information), but that her firm “isn’t there yet.”

Forcing Santa to go mobile has opened him up to occasional abuse

We’re all working from everywhere now, and Santa is not an exception. Over the past decade, according to Hancock, more mall managers have begun asking their Santas to roam shops and food courts wearing the hot, heavy suit, to both increase the number of shoppers he’ll interact with and reduce the amount of real estate dedicated to Santa’s village, says Hancock. That space can be better used to house additional shops or kiosks.

But roaming has also left Santas less secure. One performer told the researcher about a group of teenagers in a UK mall who followed him around pulling on his beard and shouting obscenities. Another Santa was nearly mugged, though he stayed in character throughout the ordeal. He told his assailant, “Santa is like the queen. He doesn’t carry money.”