At Christmas mass, a 12-year-old girl becomes collateral damage in Duterte’s war on drugs

Laguna, Philippines

Laguna, Philippines

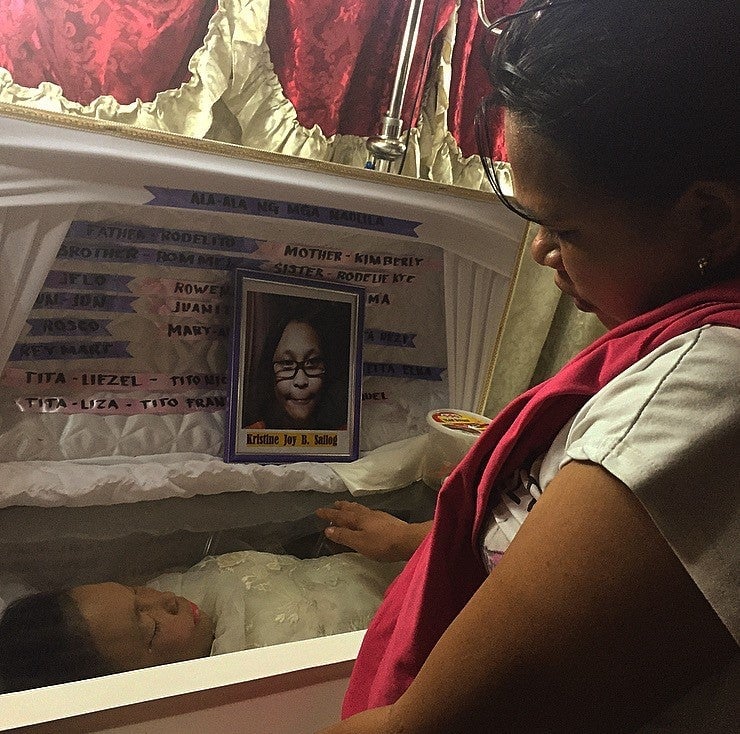

Kimberly Sailog carefully wiped the coffin’s glass cover with a red t-shirt, looking lovingly at her daughter beneath it. Though small and slender, the white box filled nearly the entire first floor of the Sailog home, a small shanty cobbled together with metal and plywood in a village south of Manila.

Atop the cover sat a container for funeral donations, a small plate of food, and a live yellow chick, now a recognized fixture in wakes like this one, where the victim was killed by an unknown attacker. It is believed that the chick will haunt the perpetrator and peck at his conscience.

The 12-year-old victim’s name was Kristine Joy Sailog. Her parents called her Tin-Tin or Bunso, the Filipino word for “youngest.” Like many girls her age, Tin-Tin liked daydreaming, writing in her journal, and, since getting a cellphone for her birthday last November, taking selfies.

She was among the latest fatalities in the brutal drug war waged by Philippine president Rodrigo Duterte. In the roughly six months Duterte has been in office, there have been over 6,200 drug-related killings, a combination of vigilante slayings and deaths resulting from police confrontations.

But Tin-Tin was not involved in drugs. Nor was she caught in the middle of a drug raid. Instead she was among the growing number of innocent victims hit by bullets not meant for them.

“She loved tickling my knees,” Sailog, 32, recalled softly. “Every night before going to bed, we would horse around. I’d pinch her nose, she would tickle my knees to make me laugh. She always said ‘I love you, mama’ before sleeping. Now, it’s as if she is just sleeping.”

A random death

On Dec. 21, Tin-Tin asked her mother to attend evening mass, or Misa de Gallo, with her. The nine-day novena mass is a popular Christmas tradition for many Filipinos. Tin-Tin had not been able to attend the previous masses, but it was her brother’s birthday. She begged her mother to buy ice cream afterwards to celebrate.

Sailog did not want to go. The mass would probably end at around 10pm, and she was exhausted from working a full day as a cleaner.

“I saw how disappointed she was, so I gave in,” she recalled.

In the middle of the homily, Sailog got up to go to the bathroom just outside the church, and Tin-Tin insisted on going with her. In the parking lot, Tin-Tin, who was walking behind, called out, “Mama!” Sailog saw her on the ground and thought she had tripped. When Tin-Tin didn’t get up, Sailog realized with horror that her daughter had been shot.

“I heard the shots, but I thought there were fireworks at first. Then I saw Tin and all the blood, and I started to scream. They closed the doors to the church. No one would help us,” said Sailog, tears rolling down her face.

A driver of a motorized rickshaw finally stopped and brought them to the hospital. “I kept telling her not to let go. ‘Don’t leave mama,’ I begged her.”

Later Rodelito, Tin-Tin’s father, stood outside the family’s small house and greeted mourners. Among them were relatives, Tin-Tin’s classmates and friends, and parents from the neighborhood. He stayed outside most of the time, unable to bear seeing his daughter lying in the coffin.

“When I see her lying there, I can still see her lying in the hospital,” he said. “The doctors kept pumping her chest trying to revive her. They tried nine times. She did not want to die.”

Rodelito, 40, watched helplessly as blood flowed out each time doctors pumped her chest. He felt his anger rising as his daughter’s blood splashed onto the floor, stepped on by doctors and nurses. He was overcome with grief when Tin-Tin succumbed to cardiac respiratory failure, caused by a single bullet that hit her on the right side and lodged in her ribs.

Accounts by witnesses, community officials, and police reports vary, but it seems while there were three victims of the Dec. 21 church shooting, only one was an intended target: Allan Fernandez, a village watchman. According to local officials and police, the 36-year-old was one of three people assigned to manage traffic at the intersection as churchgoers came to hear Christmas mass.

A statement seen by Quartz and made by eyewitness Michael Desuasido, one of the two other people on duty with Fernandez, claimed that the shooting was carried out by four men riding two motorcycles, both lacking license plates. Their faces were covered by helmets and handkerchiefs tied around their faces. One gunman wearing a black jacket took aim at Fernandez.

After the first bullet hit him in the chest, Fernandez ran into the church parking lot, presumably to use the cars as cover. More shots were fired. Two more bullets hit him in the chest. Another hit Tin-Tin, and one struck another churchgoer, 46-year-old Rowena Gayap, in her lower abdomen. Gayap survived the attack and is currently recovering from her injury.

Manuel J. Mercado, a village official, said that Fernandez was a former drug user. Under the government’s crackdown on drugs, he was one of the hundreds of thousands in the country who surrendered himself to the police, signing a waiver promising that he would no longer do drugs.

As a village watchman Fernandez earned about $50 a month, and he was apparently trying to turn his life around. But there were rumors he had gone back to using drugs, maybe even selling again.

Riddled by corruption

Public opinion polls show that over 70% of Filipinos support the war on drugs—but that eight out of 10 fear that they or someone they know might become a victim of an extrajudicial killing. The somewhat contradictory findings reflect the lack of confidence Filipinos have in the nation’s dysfunctional judicial system, where cases can take anywhere from five to 15 years to be tried.

“Our justice system is riddled by corruption, and justice has become an illusion for Filipinos,” said Budit Carlos, spokesperson for the Defense of Human Rights and Dignity Movement (iDefend). As a result, many are willing to accept justice that comes in the form of swift retribution rather than due process.

Florentino Reyes, a member of the village task force of volunteer watchmen, said he felt sorry for Fernandez but insisted that the government’s anti-drug policy is a good one. Reyes voted for Duterte based on his promise to clean up the streets, and said he is satisfied that the president is keeping his promise.

“I’m not the only one who voted for him, the whole Philippines did,” said Reyes, even though Duterte won with just 16.6 million votes—not even half of the eligible 54 million voters. “I know it’s bad to kill people, but then people shouldn’t do drugs. Everyone knows Duterte’s policy about drugs. The drug problem is so bad that if Duterte doesn’t do something about it, we will be ruined as a nation.”

The parish priests were not available for a statement, but parish secretary Cristy Gutierrez expressed concern about how traditional places of refuge like churches have become a frontline for waging the drug war.

“If things like that need to be done, they should at least not do it in a church. They should show some respect for the church and the churchgoers,” said Gutierrez.

From his campaign to his inauguration speech, Duterte has consistently positioned illegal drugs as one the “symptoms of a virulent social disease that creeps and cuts into the moral fiber of Philippine society.” He claims that there are three to four million people who are dependent on drugs in the Philippines. Duterte warns that that number will increase to 10 million, turning the Philippines into a country overtaken by drug users whom he labels as “zombies” who are “sub-human.”

Speaking out

These claims have been proven baseless and erroneous. Research shared by the nation’s Dangerous Drugs Board suggests that current drug users make up 2.3% of the population aged 10 to 69, or about 1.8 million people. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, meanwhile, estimates that the highest-ever recorded figure for the prevalence of amphetamine use in the Philippines is 2.35%, comparable to the prevalence rates of 2.2% in the US and 2.9% among Australian males.

Outside the Philippines, Duterte’s drug war has received a chorus of harsh criticism. In October 2016, the International Criminal Court issued a statement in which chief prosecutor Fatou Bensouda said:

I am deeply concerned about these alleged killings and the fact that public statements of high officials of the Republic of the Philippines seem to condone such killings and further seem to encourage State forces and civilians alike to continue targeting these individuals with lethal force.

Duterte has brushed off such condemnation with expletives and threats. He called US president Barack Obama a “son of a whore” and flashed the European Union the middle finger when they expressed concern over his administration’s efforts to curb drug use. He has flip-flopped on his position to invite the UN to conduct an independent investigation on the killings. A visit scheduled for early this year remains pending because of conditions set by the Duterte government.

Meanwhile, opposition on the home-front is drowned out by Duterte supporters, who are loud and often vicious on social media. Many claim that the streets are safer because criminals are scared. They also point to achievements of the Duterte administration, like subsidies for medication, hospitalization, and college education. Duterte is particularly popular among the millions of Filipinos working abroad, many of whom cling to his promises that he will bring them home by improving the economy and creating more jobs.

But more groups and institutions are coming together to voice their opposition. Human rights organizations like iDefend regularly hold candlelight vigils for the victims—now known by the abbreviation for extrajudicial killings, EJKs. The Network Against Killings in the Philippines (NAKPhilippines)—a coalition of human rights advocates, civil society organizations, church groups, and family members of victims formed in November—has condemned the government’s inaction in investigating the killings.

“Since the start of Duterte’s war on drugs, not a single law enforcer has been brought to court to answer allegations of extrajudicial executions during so-called ‘legitimate police operations,'” noted NAKPhilippines in a statement. Father Amado Picardal, a group spokesperson, added, “We fear not only a lack of accountability but possible government cover-up for these crimes.”

Among politicians, opposition is loudest from vice president Leni Robredo and senators Antonio Trillanes IV and Leila de Lima. Since her opposition de Lima has been accused of accepting drug money during her stint as justice secretary, and she’s become the target of threats after her mobile number and home address were made public during a congressional hearing. Later, Congress considered a public release of an alleged sex tape of de Lima and her former bodyguard and driver as part of evidence. The viewing was shelved in the face of protest by lawmakers and women’s groups.

A display of protest

The nation’s Catholic Church has been criticized for its silence and perceived apathy toward the drug war, even as thousands are being gunned down in the streets.

But some local churches have taken a stand. Priests at the Redemptorist Church of Baclaran, among the city’s busiest, lined the entrance with photos of drug-war victims and their anguished loved ones. The pictures were taken by both photojournalists and the church’s own Brother Jun Santiago.

“Maybe with the small thing [the photo exhibit] we’ve done, the Church will awaken a little that we need to speak, and we don’t have to be silent,” said reverend Joseph Echano in an interview with Philippine online news outlet Rappler.

His church has long offered funeral assistance to the poor and reports that the number of requests for such help has risen over the past six months. Priests on the night beat offer prayers, assistance, counseling, and referrals to legal assistance. The photo exhibit is their most public statement in protest of the killings.

Yet Duterte still enjoys immense popularity. The latest polls released in December show his approval ratings have slipped, but remain at a high 72%. His enduring popularity may explain the deafening silence of opposition to the drug war, and why there is little sympathy for victims like Fernandez.

Two days after the shooting, Fernandez’s body was still at the morgue. There were no family members waiting to say goodbye. There was no home that could be used to hold a wake.

His live-in girlfriend was afraid for her safety and keeping a low profile, according to police and village officials. She and her children from another relationship live in a shanty that she and Fernandez rented. The landlord refused to allow her to hold a wake there.

According to Mercado, since Fernandez was technically a local village employee, they would make use of the community center for his wake. Expenses for both Fernandez’s and Tin-Tin’s wakes would be paid for by the local government budget.

“Tin is crying”

The Sailog family decided to bury Tin-Tin on Dec. 29. In her journal, Tin-Tin wrote that she hoped for health and happiness for her family and that they would always be together.

As Kimberly Sailog quietly cried while recounting the events of Dec. 21, her eldest daughter, Kaye, watched over her sister’s coffin and nudged her mother: “Mama, Tin is crying.”

A single tear had formed in Tin-Tin’s right eye and lodged itself there before it slowly rolled down the side of her face.

Sailog stood up and started caressing the glass that separated her from her daughter. “Baby, don’t cry. I’m sorry Mama is crying. Bunso, don’t cry. I’ll try not to be sad anymore so you won’t be sad either.”

She wiped her tears with the red t-shirt, the same one she used to clean the coffin’s cover. “This is my t-shirt, but Tin loved wearing my clothes and her father’s before washing them,” she said. “This is what she last wore. I raised her, took care of her, only for her to be taken away from me in an instant, just like that. It’s hard to accept.”