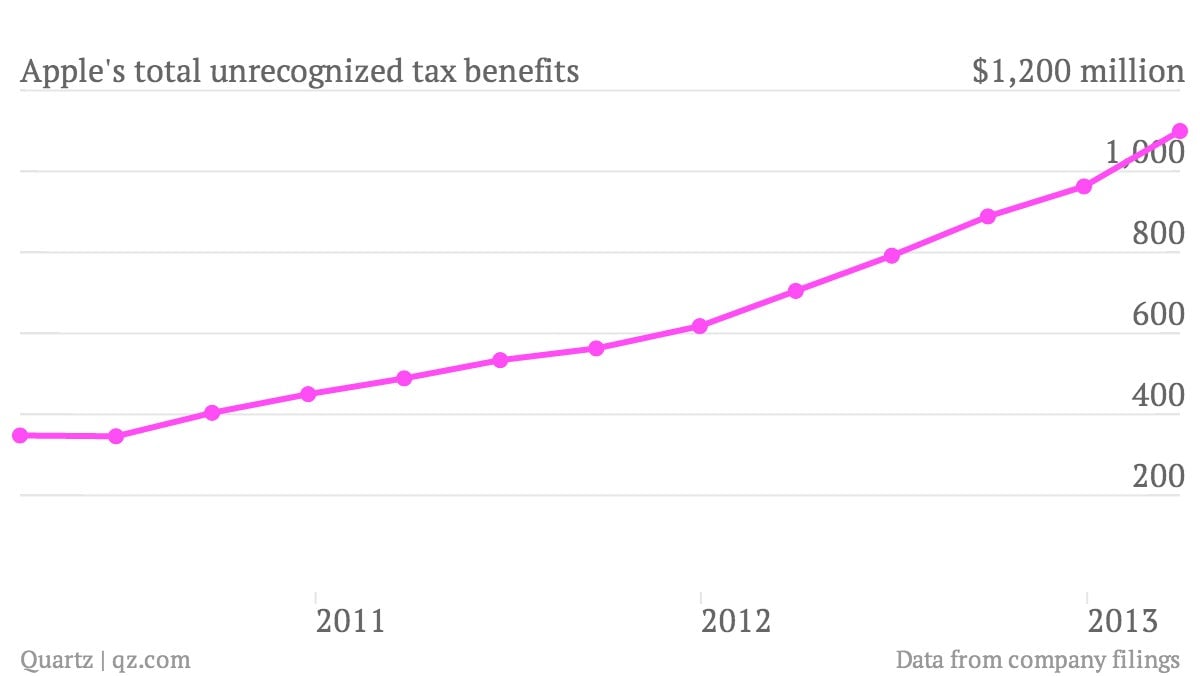

Apple’s $1.1 billion worth of tax breaks it doesn’t expect to get away with

Apple was under scrutiny this week for allegedly dodging corporate income taxes on big chunks of its profits in recent years, much of it through controversial but perfectly legal maneuvers involving overseas subsidiaries.

Apple was under scrutiny this week for allegedly dodging corporate income taxes on big chunks of its profits in recent years, much of it through controversial but perfectly legal maneuvers involving overseas subsidiaries.

But the company freely admits that it hopes to benefit from hundreds of millions of dollars in tax breaks that are probably too aggressive to pass muster with tax authorities. The figure has been rising in recent years, and now stands at $1.1 billion, up from $348 million just three years ago.

Technically, that’s just a subset of some $3.2 billion in so-called “gross unrecognized tax benefits” on Apple’s books. These amount to tax benefits—deductions, credits, etc.—that the company has claimed on its tax returns, but which it thinks have less than a 50% chance of surviving an audit. In other words, they’re aggressive tax positions that aren’t likely to succeed—but which the company is pursuing anyway.

Apple hadn’t responded to a request for comment before publication.

About two thirds of the $3.2 billion boils down to issues of timing—whether a tax break kicks in now or later, which doesn’t fundamentally alter the amount of tax the company pays in the long run, or its effective tax rate.

But the rest, totaling $1.1 billion as of March 30, are essentially permanent deductions or credits that “would affect the Company’s effective tax rate” if recognized, Apple says in its most recent quarterly report. Those are the tax breaks that matter, notes Jack Ciesielski, an accounting expert who testified at a previous Senate hearing on companies’ offshore tax-avoidance schemes and who publishes The Analyst’s Accounting Observer, a widely read service for securities analysts.

From a shareholder’s perspective, the accounting treatment for these aggressive maneuvers is conservative. Apple ignores them in calculating its effective tax rate, essentially assuming that they won’t pan out. Accounting rules let Apple book the tax benefits it claims on its returns only if there’s a good chance that a given benefit will survive an audit. (The rules assume everything is audited, which is a good bet with the biggest companies.)

“They go for the gusto, they go for the aggressive thing on the tax return,” Ciesielski told us, “but in the report to investors they say it’s more likely than not that they couldn’t take [the tax break].”

As a result, shareholders don’t lose out if Apple fails to capture the tax breaks, but do win out if it succeeds. If an audit fails to invalidate some of the tax breaks, the company’s effective tax rate would go down from its current level of about 26%. And that’s pretty likely, says Donna Bobek Schmitt, an associate professor specializing in tax at the University of Central Florida. She has had students track down Apple’s gross unrecognized tax benefits as part of a class exercise (pdf).

“They’re telling you that if they lost on all of them—which, by the way, no one ever does—it would have no effect on their tax expense,” Bobek Schmitt says. “But if they won on any of them, it would lower their tax rate.”

Like most companies, Apple doesn’t say which tax benefits it expects to flame out. Chances are good that many of them involve transfer pricing, Bobek Schmitt says—essentially, the fees that one Apple subsidiary charges another for services or the use of patents and other intellectual property, which is a common point of contention with tax authorities. (Bloomberg News has a more detailed look at various ways of measuring Apple’s tax bill.)

Apple is far from the only big company booking these unrecognized tax benefits. Google reported $2.07 billion of them as of the end of March, including $1.89 billion that could alter the company’s effective tax rate, which was 7.9%. General Electric reported $5.58 billion, of which $4.19 billion could alter its effective tax rate (12.4% as of March 31).