Paris is blaming Airbnb for population declines in the heart of the city

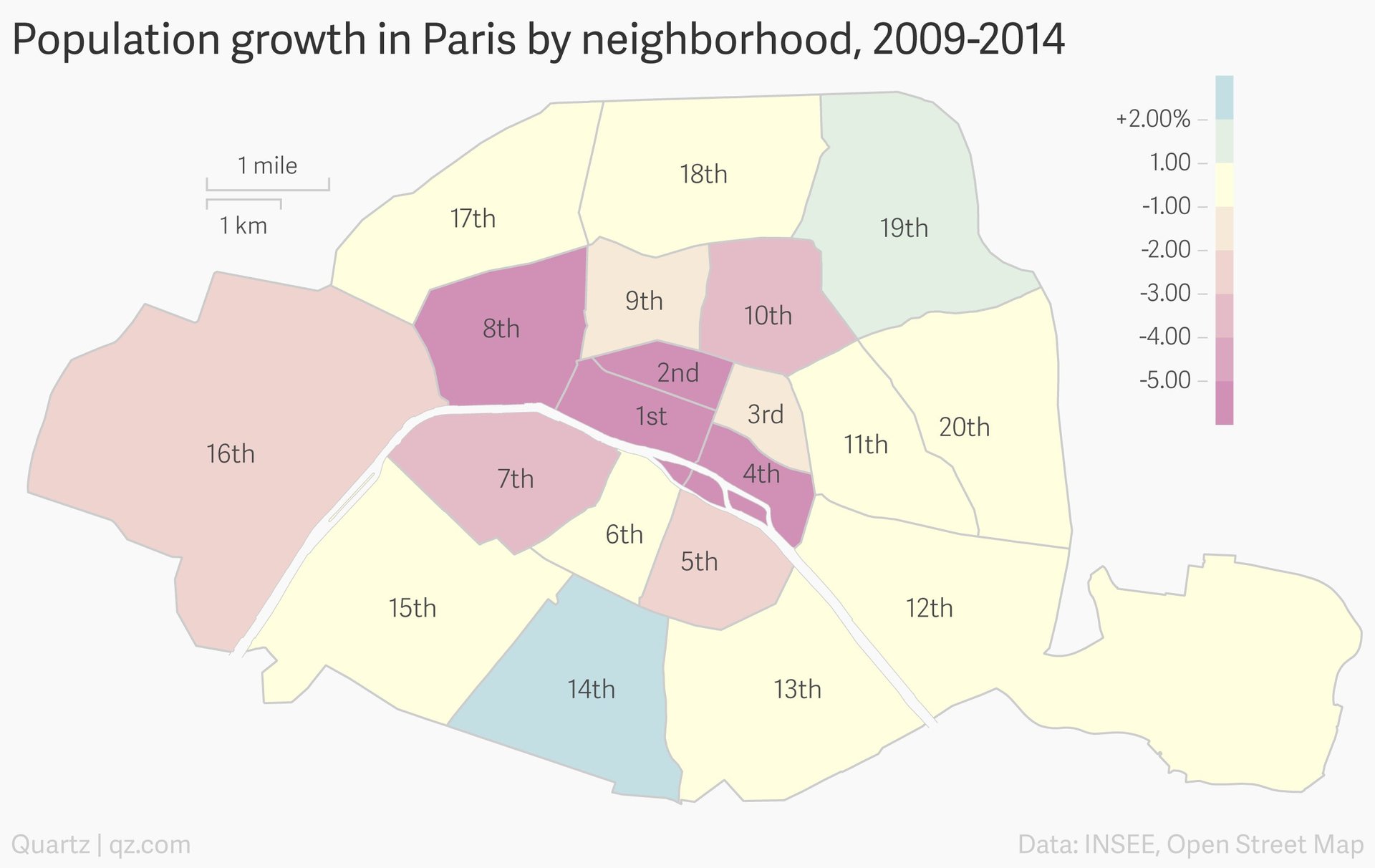

Between 2009 and 2014, the number of people living in Paris’s 1st arrondissement, a small, touristy district that’s home to Louvre, fell by 5%. Three other neighborhoods in the heart of the city—the 2nd, 4th, and 8th arrondissements—saw similar population declines during that period, according to data published Jan. 2 by Insee, France’s National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies. Citywide, the population decreased by 13,600 people, or about 0.6%.

Between 2009 and 2014, the number of people living in Paris’s 1st arrondissement, a small, touristy district that’s home to Louvre, fell by 5%. Three other neighborhoods in the heart of the city—the 2nd, 4th, and 8th arrondissements—saw similar population declines during that period, according to data published Jan. 2 by Insee, France’s National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies. Citywide, the population decreased by 13,600 people, or about 0.6%.

Paris blames Airbnb.

The Paris mayor’s office attributed (link in French) the falling urban population to lower birthrates, but also to an increase in second homes, particularly those rented out seasonally to tourists. Meanwhile, 1st arrondissement mayor Jean-François Legaret told Le Parisien that Airbnb “has been a catastrophe for central Paris.”

Insee wasn’t quite that definitive. The national statistics office credited Paris’s population drop to several causes: lower birthrates and second homes, to be sure, but also an increase in deaths, and higher living costs that are leading young people to settle down outside the city.

“Airbnb is indeed likely to emphasize this tendency by reducing the number of available apartments,” Insee spokesman Olivier Leon wrote in an email. “These ‘Airbnb apartments’ have zero inhabitants (they are considered as second homes) and can increase the prices of the other housing, which gets less and less numerous.”

A spokesman for Airbnb countered that Parisian hosts “are typically long-term residents” of the city who “share their space for 25 nights a year,” adding that 55% of them earn less than the median French salary. In 2015, Airbnb said that the 11th and 18th arrondissements had the most bookings; both are outside the city center. There were about 11,300 Airbnb listings in Paris at the end of 2014, according to data from Airdna, a third-party analytics firm.

While the figures released by Insee are considerably outdated, any intimation that Airbnb lowers residential populations is bad branding. Regulatory scrutiny of Airbnb intensified last year over fears that home-sharing makes room for tourists at the expense of residents. New York’s governor signed some of the toughest limits on short-term apartment rentals in the country. Berlin lawmakers enacted restrictions on home rentals that carry fines of up to €100,000. And Santa Monica, California, convicted its first host for renting out units illegally.

Paris and Airbnb already have a complicated relationship. The French capital is Airbnb’s second-biggest market—behind only the New York City metro area in terms of total listings, according to Airdna. Paris’s first deputy mayor has called Airbnb a “great example” of innovation, and in 2015 the company hosted its annual home-sharing conference there, its first iteration outside of San Francisco. Airbnb also struck a deal to collect and remit tourist taxes in Paris, which translated to €1.17 million (about $1.31 million) in the fourth quarter of 2015.

But the city has remained wary of letting home rentals spread unchecked. In January 2016, Paris authorities raided apartments in the 1st and 6th arrondissements to identify landlords who were renting out their units past the legal limit of 120 days per year, threatening offenders with fines of up to €25,000. In March, Airbnb said it would work with Paris City Hall to ensure hosts followed local rules.

It’s hard to say how much responsibility home-sharing really bears for the population shifts that occurred in Paris, a city of 2.2 million people, between 2009 and 2014. But local officials’ willingness to point the finger at Airbnb suggests their patience with the company is wearing thin.