The only way to get into America is through this 60,000 strong, pro-Trump armed force

The chaos unleashed by Donald Trump’s Jan. 27 executive order on immigration was swift and widespread, upending the lives of hundreds of travelers and their families, and threatening access to the US for tens of thousands more. It also created nothing less than a constitutional crisis at airports in some of the US’s largest cities.

The chaos unleashed by Donald Trump’s Jan. 27 executive order on immigration was swift and widespread, upending the lives of hundreds of travelers and their families, and threatening access to the US for tens of thousands more. It also created nothing less than a constitutional crisis at airports in some of the US’s largest cities.

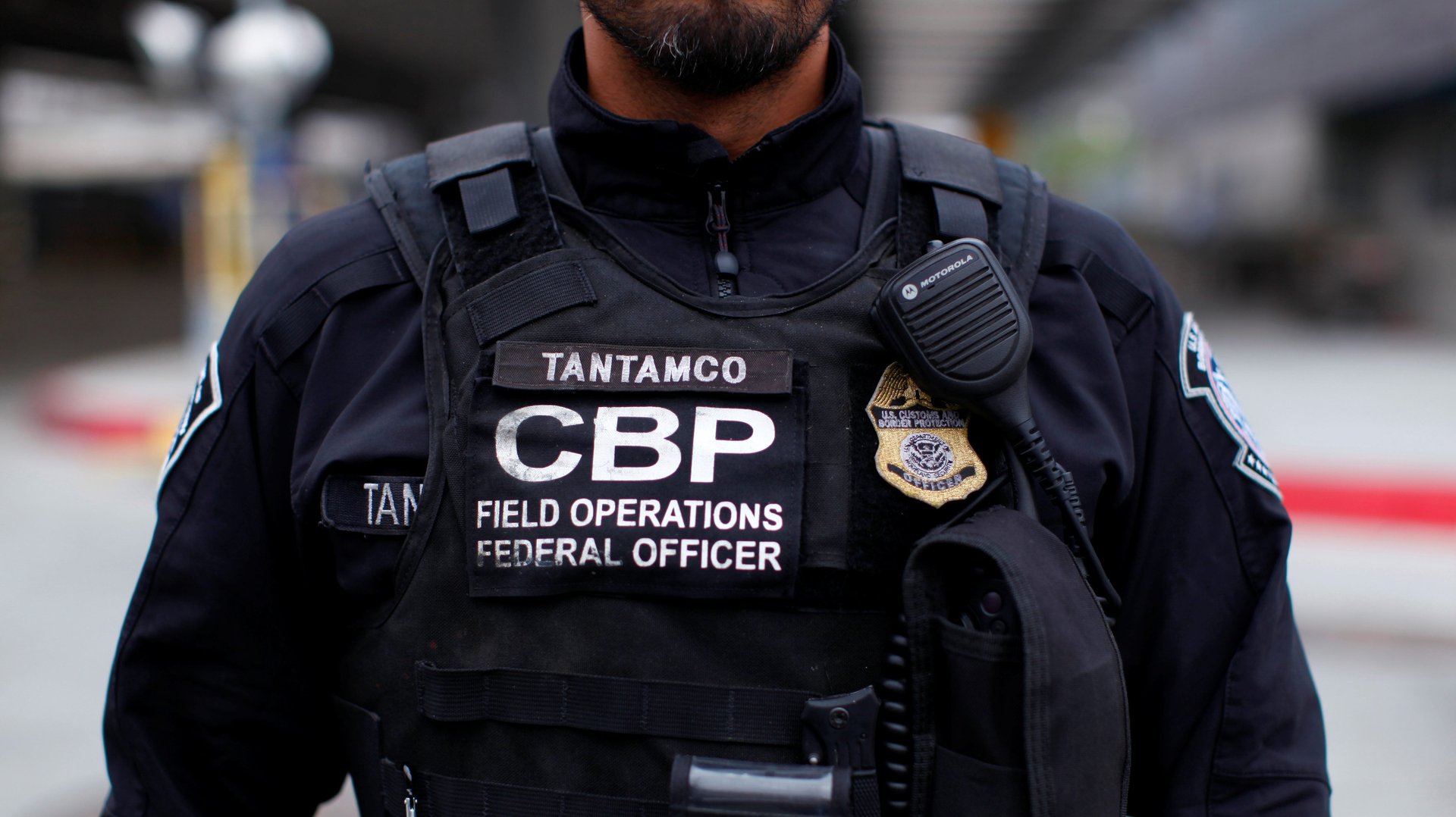

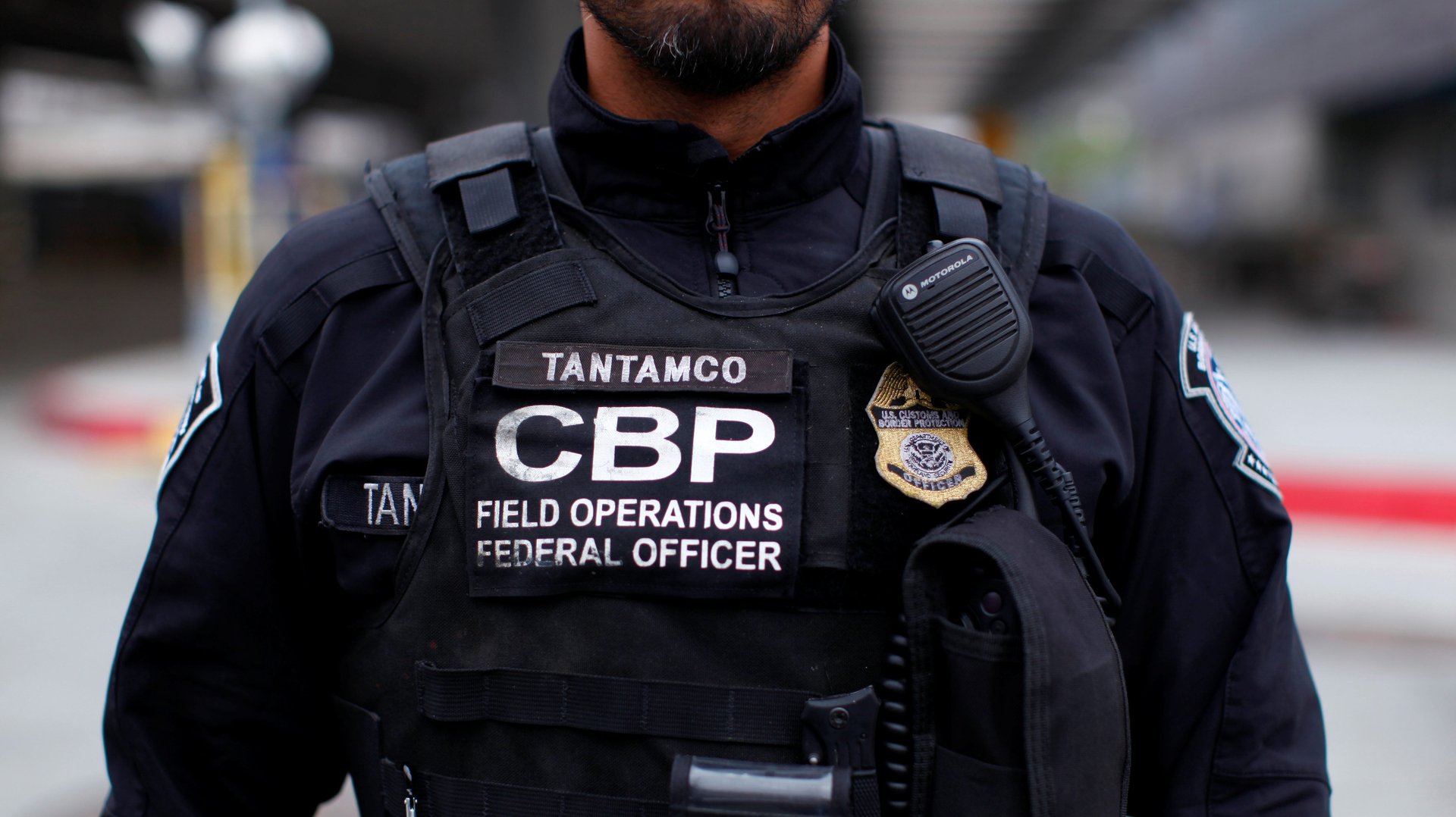

As part of the US Department of Homeland Security’s largest law enforcement body, the 60,000 employees of the US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) are tasked with policing the migration of goods and people in and out of the country, with two-thirds of them manning border crossings, airports, and ports. The agency is part of the executive branch of government, which means it answers to the White House—and is subject to the same checks and balances, from the legislative and judiciary branches, as the administration.

But in the wake of Trump’s attempted policy change on immigration, CBP officers refused to comply with a Brooklyn court order, issued hours after the president’s executive action, that temporarily blocked travelers nationwide from being deported. They also ignored demands from other federal judges that the CBP let travelers see lawyers.

Instead, officers forced some travelers back on planes, and detained others for as long as 30 hours with no explanation, and little food or water. Some travelers were handcuffed. Others were coerced into signing away their legal rights to stay in the US, according to lawyers, congressmen, and lawsuits filed afterward. CBP officers often refused to speak to the legislators and civil rights lawyers who were trying to stop them, saying they were taking orders directly from “Washington DC,” occasionally referencing the White House or president Trump directly.

Since then, the legality of Trump’s travel ban has worked its way up the courts. After the order was suspended nationwide on Feb. 4 by a federal judge in Seattle who granted a temporary restraining order, the Trump administration appealed. Its request to have the restraining order lifted was denied on Feb. 10 by three judges on the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals. Now the case could go to the US Supreme Court, if the White House doesn’t try its hand at a new, revised order (which could set off a new cycle of legal maneuvering).

However the policy lands, CBP will be its primary enforcer.

The initial ban was hugely popular among CBP officers, who backed Trump in large numbers during the election and affirmed their support in the wake of the executive action on immigration. According to a joint statement by the union councils representing the border agent employees of the CBP and Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), which also enforces border protection laws, morale among agents and officers “has increased exponentially since the signing of the orders. …President Trump’s actions now empower us to fulfill this life-saving mission, and it will indeed save thousands of lives and billions of dollars.”

The CBP itself called the executive order “lawful and appropriate,” even after the federal courts ordered it be stayed.

A “military junta”?

As concerns swirl over the Trump administration’s unorthodox approach to everything from crafting executive policy to governing with conflicts of interest, the CBP’s actions in the days after Trump’s executive order have drawn heavy scrutiny. Several Democratic congressmen have called for an investigation into the president’s instructions to the CBP, warning that the US could become a “military junta” if the system of checks and balances breaks down.

Some Republicans, too, have criticized the order, and its aftermath, calling it “unacceptable” and “not properly vetted,” a measure that created “confusion and uncertainty.” None addressed the CBP’s actions directly, instead focusing their criticism on the White House itself.

Trump, meanwhile, has been hounding the judiciary. True to form, on Feb. 4 he got on Twitter to mock the Republican-appointed judge in Seattle who suspended his order. On Feb. 8, Trump told a group of police chiefs he met with that the US “courts seem to be so political,” adding that it would “be so great for the justice system if they’d be able to read a statement and do what’s right.” And on Feb. 10, he responded to the appeals court decision by tweeting, in all caps, “SEE YOU IN COURT, THE SECURITY OF OUR NATION IS AT STAKE.”

And the CBP continues alarming practices—refusing entry to a Muslim Canadian woman bringing her cancer-stricken son to visit relatives in the US, after searching her phone and questioning her about how she feels about Trump, for example.

The situation is sending chills down the spines of Americans who have experienced authoritarian regimes. “I’ve seen what a totalitarian government can do,” says immigration lawyer Faith Nouri, who lived through a revolution and totalitarian power when she was growing up in Iran. “I never thought I’d see something like that here” in the US, she says.

When government security agents like the CBP start ignoring the courts, “there’s a name for that—it’s a coup,” says another American veteran human rights advocate and lawyer with extensive experience in authoritarian regimes, who isn’t authorized by her employer to speak about the Trump regime.

“I’m not saying that’s where we’re at, but I’m saying that’s where this leads,” she says. The US’s venerated system of checks and balances “only exists and functions because we’ve all agreed to do things that way. It’s a very, very thin veneer of civilization, and all it takes is one autocrat to smash it to bits.”

From LA to DC, an “iron curtain”

Trump’s executive action on immigration ordered that citizens of seven Muslim-majority countries be barred from entering the US for 90 days, and all refugees halted from entering the country for 120 days. When the text of the order came out hours after Trump signed the paperwork, green-card holders learned it affected them as well. US green-card holders are given the right to permanently live and work in the US. Often they are on the path to becoming citizens. They pay taxes, are eligible for military service, and can vote in local elections.

Thousands of lawyers raced to the US airports, working overnight, often pro bono, trying to make contact with people detained by immigration authorities, whose distraught family members could not reach them.

Travelers were arriving, and then not coming out of the airport, says Mana Yegani, an immigration lawyer in Houston. Their family members, many of them US citizens themselves, couldn’t get any information about why their loved ones were being held. The CBP “wouldn’t allow attorneys to talk to clients,” despite a ruling from the federal judge in Brooklyn which had said CBP should provide a list of detainees and allow them to speak with lawyers, Yegani says.

As the situation escalated, protestors and local congressmen arrived at the Houston airport to the show their support, but again, the CBP stonewalled. Democratic congresswoman Sheila Jackson Lee went to the Houston airport to speak with the CBP directly, but none of their officers or supervisors would come out to speak with her. The congresswoman is on the House’s Homeland Security Committee.

Desperate, attorneys tried to enlist security guards to relay messages. “It was almost like this iron curtain” between detainees and the people who were trying to help them, Yegani says. “Just by Trump signing something, it created this cascade of chaos and people’s lives were torn apart.”

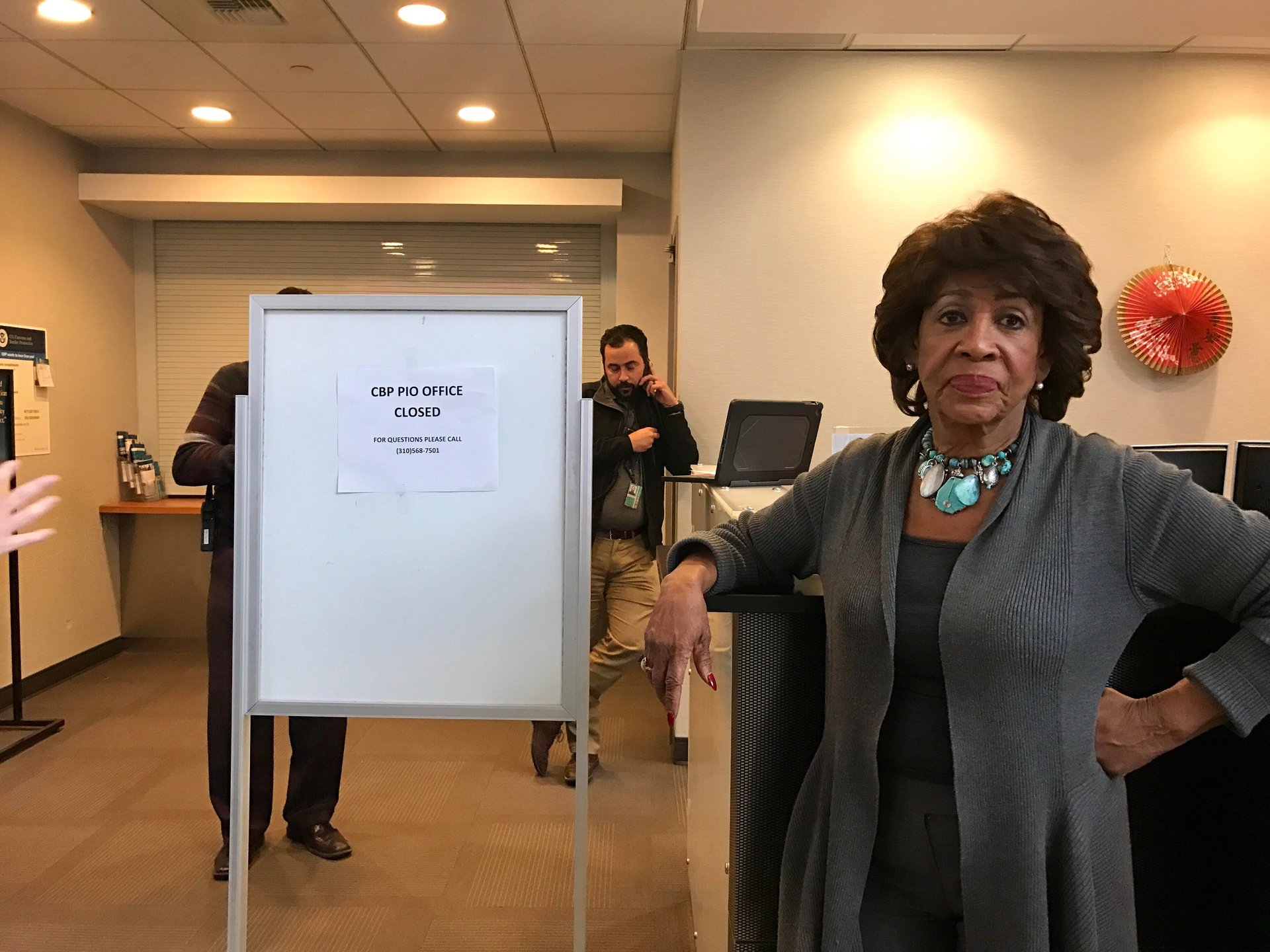

At Los Angeles International Airport, the CBP declared its offices closed on Jan. 29, and left a phone number that was never answered. Officers refused to speak to lawyers and local politicians, including Democratic congresswoman Maxine Waters.

Attempts to get the CBP to comply with the Brooklyn court order turned into a frustrating, several-day ordeal in Los Angeles, says Nouri, who is based in Huntington Beach, California. Lawyers contacted local US marshals to “accept service,” or officially recognize the New York order, and request compliance with it. But the marshals refused to accept service and referred lawyers to the local US attorney general, who also refused to accept service, Nouri said. But the Brooklyn court order had specifically ordered US marshals to help with compliance if the CBP refused.

“I have been told by every single one of these people ‘We are following orders from Washington,’” Nouri says.

The California Attorney General and the local US marshals office didn’t respond to requests for comment on the situation. California’s Attorney General has joined more than a dozen other states in opposing the immigration ban.

In New York, a Sudanese green-card holder was handcuffed, and an Iraqi translator who worked with the US Army was detained for 18 hours. Several elderly couples were detained for more than 30 hours, a lawsuit alleges. Another was held for at least 10 hours without food.

Even after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, Muslim families traveling through US airports were not treated in the same manner, Nouri says. Instead, in that time, immigration officers sat down with lawyers to explain new procedures, took questions, and engaged in discussions. “We had presidents in the past who were very careful not to set a precedent for across the board discrimination, or to treat Muslim US citizens as a second class citizens,” Nouri says. “We don’t have that now.”

In Washington DC, CBP officers allegedly bullied “dozens—if not hundreds” of legal immigrants into giving up their immigration status by giving them false information, according to a lawsuit that was joined by the state of Virginia’s attorney general Mark Herring, a Democrat. According to the complaint, officers

lied to immigrants arriving after the Executive Order was signed, falsely telling them that if they did not sign a relinquishment of their legal rights, they would be formally ordered removed from the United States, which would bring legal consequences including a five-year bar for reentry to the United States.

The lead plaintiffs in the case were “handcuffed, detained, forced to sign papers that they neither read nor understood, and then placed onto a return flight to Ethiopia just two and a half hours after their landing,” the complaint says.

Not all travelers had bad experiences with the CBP. In Seattle, for example, officers carefully explained the implications of the order, according to attorneys. Immigration lawyers and travelers also told of officers who quietly delivered food to breastfeeding mothers detained for hours, or medicines to elderly travelers who needed to take them regularly, sometimes calling outside of work hours to check if the travelers were okay.

The expanding CBP

With an annual budget of $13 billion and 60,000 employees, the CBP is tasked with the daily screening of more than 1 million foreign entrants and 67,000 cargo containers arriving in the United States. Officers look for everything from drugs to criminals to intellectual property violations. Created after 9/11 through a combination of parts of the customs and immigration agencies, the agency now employs 22,910 CBP officers stationed at airports and other ports of entry and another 19,828 border patrol agents, who monitor the US’s geographic borders.

Frustrations with Obama-era immigration policies pushed many agents and officers to vote for Trump, according to interviews with several retired CBP officers. Few unions endorsed Trump as enthusiastically as that of the National Border Patrol Council, which represents 75% of Border Agents. It said:

Mr. Trump is as bold and outspoken as other world leaders who put their country’s interests ahead of all else. Americans deserve to benefit for once instead of always paying and apologizing. Our current political establishment has bled this country dry, sees their power evaporating, and isn’t listening to voters who do all the heavy lifting.

That endorsement came in part because of the resurgence of a controversial George W. Bush administration policy called “catch and release.” Critics object to the policy, which allows people illegally in the US to be released by authorities for a later court date, rather than jailed or returned to their country of origin. The policy was suspended in 2006, but essentially reinstated in recent years, as US federal courts ruled that grim detention centers housing minor kids and their parents were illegal.

Rather than chasing down criminals or preventing illegal entries, Border Patrol agents found themselves processing reams of paperwork and buying baby wipes instead—as tens of thousands of people, including unaccompanied children, fled gang violence in Central America and sought asylum in the US.

Away from the country’s borders, a new “priority enforcement” program announced in late 2014 meant officers were only supposed to target illegal aliens convicted of major crimes or gang members, leaving the majority alone. “The Border Patrol is used to deterring entry and apprehension, and they weren’t allowed to do that,” a Homeland Security special officer who worked on immigration explained.

In interviews, retired Border Patrol agents explained that their support for Trump was tied to their frustration and fear that gang leaders were leaching into the US from Central America.

“The people in Washington don’t know,” how many criminal elements may be coming across the border, but Trump does, said Steven R. Golda, a retired agent who patrolled the southern California border, just as his father did before him. Trump reached out to border patrol agents and went to town hall meetings, he said, and then “people came out and voted for him from all nooks and crannies.”

A Jan. 25 executive order from the Trump White house calls for the hiring of 5,000 more border agents “as soon as is practicable,” although the White House had issued a federal hiring freeze order two days earlier. The number would increase a workforce that’s twice as big as it was in 2000 before the terrorist attacks that felled the twin towers in New York City, killing 3,000 people.

An anti-immigrant advisor

Just days after Trump was sworn in, Julie Kirchner, a campaign strategist who was formerly the head of an anti-immigrant group, was hired as a special advisor at the CBP.

FAIR, the group Kirchner worked for for 10 years pushes “an agenda centered on a complete moratorium on all immigration to the United States and defined by vicious attacks on non-white immigrants,” says the Southern Poverty Law Center, which defines it as a “hate group.” Among other things, the group blames western US water shortages on immigrants, and its president accused immigrants of “competitive breeding.”

She still holds the role, the CBP’s press office told Quartz, but would not elaborate on what she does.

Long-time immigration attorneys say they’ve seen a shift in attitudes among immigration officials in recent weeks.

“In my opinion and observation, there has always been a ‘rogue’ element of CBP who is rabidly anti-immigrant,” said Jennifer Minear, an immigration lawyer in Richmond, Virginia. While most agents do not, a small minority of CBP agents viewed the job as “an opportunity to exclude as many foreigners as possible in what they must see as a mission to protect Americans from immigrants,” she said. The rhetoric and recent action of the Trump administration “have emboldened that anti-immigrant element and, I believe, sent the message that they may feel free to exercise their discretion in as discriminatory a manner as they choose without fear of reprisal,” Minear said.

CBP spokesman Daniel Hetlage responded to several detailed questions about the CBP’s role in the executive order by pointing to a FAQ on the company’s website. In part, the FAQ says:

CBP issued guidance to the field expeditiously upon the signing of the Executive Order. CBP has and will continue to issue any needed guidance to the field with respect to court orders. All individuals, including those affected by the court orders, are being given all rights afforded under the law.

Hanna Kozlowska contributed reporting.