The Indian government has delivered a piercing criticism of rating firms like Standard & Poor’s and Moody’s

India’s criticism of global credit rating firms is getting louder.

India’s criticism of global credit rating firms is getting louder.

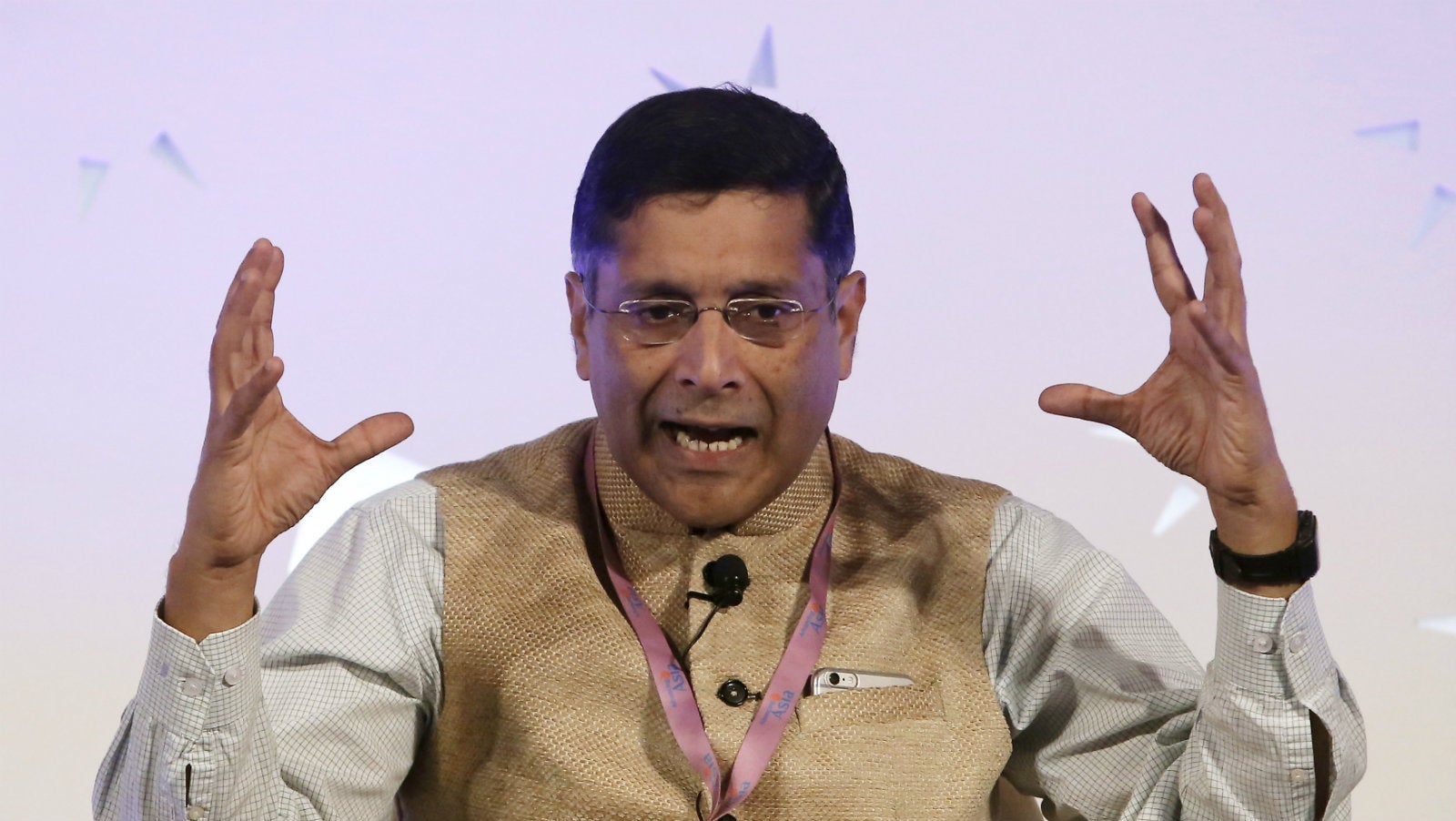

The government’s longstanding grievance over not getting a credit-rating upgrade was reiterated Jan. 31 by the country’s chief economic advisor, Arvind Subramanian. Ratings firms have “inconsistent and poor standards,” Subramanian told reporters during a media briefing on the Economic Survey 2016-17, an annual document that gives a glimpse of the state of the economy.

Standard & Poor’s (S&P) and Moody’s, for instance, have not upgraded their ratings of India—from ‘BBB-‘ and ‘Baa3’ respectively—despite its economy being one of the fastest growing globally. The firms indicated two main reasons for this: low per capita GDP and a high fiscal deficit. Both these ratings are the lowest category of the investment grade.

Subramanian finds their methodology faulty, and the reasons for this are detailed in a chapter titled “Poor Standards? The Ratings Agencies, India and China” in the Economic Survey. It is unfair, it says, to hold a country’s rating due to lack of improvement in per capita GDP—economic output per person—as it is a slow-moving variable. It typically takes a while for such an indicator to show an uptick.

Here’s what the survey had to say:

Lower middle income countries experienced an average growth of 2.45% of GDP per capita (constant 2010 dollars) between 1970 and 2015. At this rate, the poorest of the lower middle income countries would take about 57 years to reach upper middle income status. So if this variable is really key to ratings, poorer countries might be provoked into saying, “Please don’t bother this year, come back to assess us after half a century.

It also says that while the country has a high fiscal deficit (3.9% of the GDP in fiscal 2016), the comparison with other countries isn’t fair. ”India might still be able to carry much more debt than other countries because it has an exceptionally high ‘willingness to pay’, as demonstrated by its history of not defaulting on its obligations,” it explained.

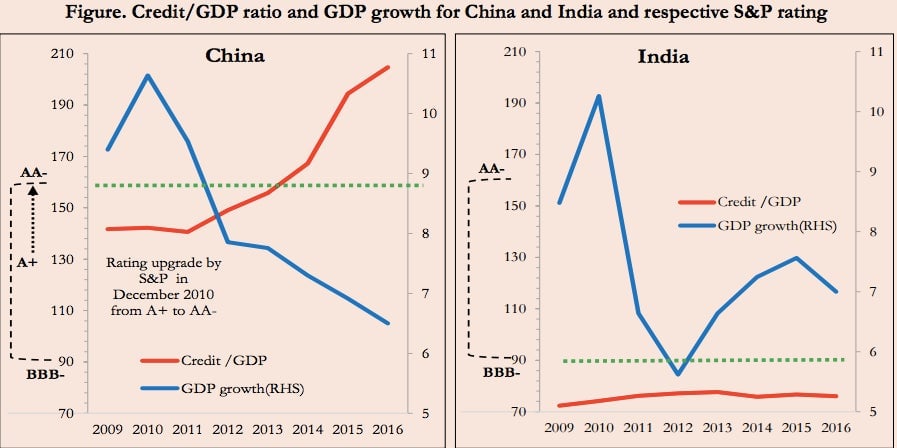

Subramanian also compared India’s economic health with that of China, which was upgraded by S&P to ‘AA-‘ in 2010. China’s high and increasing credit-to-GDP ratio, which is the ratio of national debt to GDP, along with its weak economic growth, has been considered as a threat. India’s credit-to-GDP ratio has remained relatively stable while its economy has expanded.

How did Standard and Poor’s react to this ominous scissors pattern, which has universally been acknowledged as posing serious risks to China and indeed the world? In December 2010, it increased China’s rating from ‘A+’ to ‘AA-‘ and it has never adjusted it since, even as the credit boom has unfolded and growth has experienced a secular decline.

“These contrasting experiences raise a question: can they really be explained by an economically sound methodology?” the survey adds.

Experts have said in the past that it is fair for India to expect a higher rating. ”At a moment when India’s economy is growing at very high rates, the country expects agencies to improve its ratings. Rating agencies move at a slow pace and it is understandable that India wants to have its voice heard,” Lourdes Casanova, a senior lecturer at Cornell University’s S C Johnson School of Management, told Quartz earlier this month.

Subramanian definitely wants his voice heard.