The world can now psychoanalyze Sigmund Freud’s personal life through 20,000 newly digitized letters

Sigmund Freud made it his business to explore the deep, unseemly caverns of his patients’ minds. Now the father of psychoanalysis’ own personal affects and dirty laundry are on display for the world to see, through a newly digitized collection of his personal writings.

Sigmund Freud made it his business to explore the deep, unseemly caverns of his patients’ minds. Now the father of psychoanalysis’ own personal affects and dirty laundry are on display for the world to see, through a newly digitized collection of his personal writings.

On Feb. 1, the US Library of Congress released 20,000 documents belonging to Freud, who died in 1939. His letters with his family, as well as Carl Jung, Albert Einstein, and Thomas Mann, give insight into the controversial psychologist’s theories of the unconscious, as well as the most mundane of his personal finances.

“[The collection] really exposes the complexity of the man and his ideas,” says archivist Margaret McAleer, who catalogued the collection. “In so many different ways, this collection is going to be parsed over and over and over again for meaning.” Not unlike what Freud might do himself.

In one 1910 letter from his famous correspondence with Jung, Freud complains of not feeling well and talks about the difficulty of using allegory in interpretations. In the early days of their intense friendship, Freud considered the younger Jung his intellectual heir apparent; by 1913 they had had a big falling out and broken contact.

Most of the Sigmund Freud Papers, as they’re called, are in German, so in case yours is rusty, there are a few tidbits for English readers, including a lovely 1909 postcard of the Statue of Liberty from Freud to his wife, Martha:

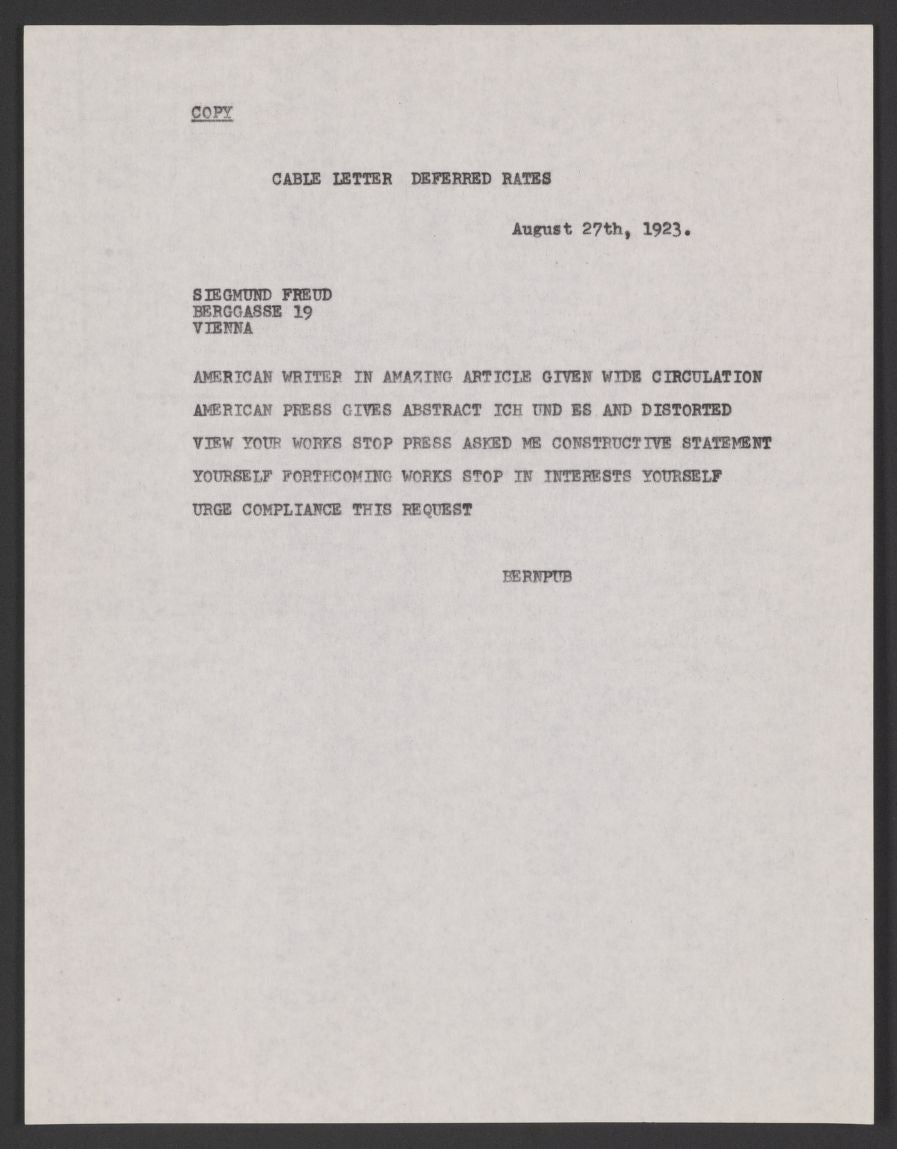

One great exchange is with Edward Bernays, who is sometimes called “the father of public relations.” Bernays lived in New York and had clients and a profound, psychological approach to advertising that would have turned Don Draper green-eyed. He was also Freud’s nephew. In a series of letters and one great telegram exchange, Bernays and Freud discuss late royalty checks for the latter’s book, most likely Beyond the Pleasure Principle.

Through the exchange, Bernays convinces his uncle to let him act as his agent in the US. His PR skills really come to the fore when he thinks that US journalist Dorothy Thompson has misinterpreted one of Freud’s ideas. Bernays asks his uncle to clarify, and sends an urgent follow-up cable message:

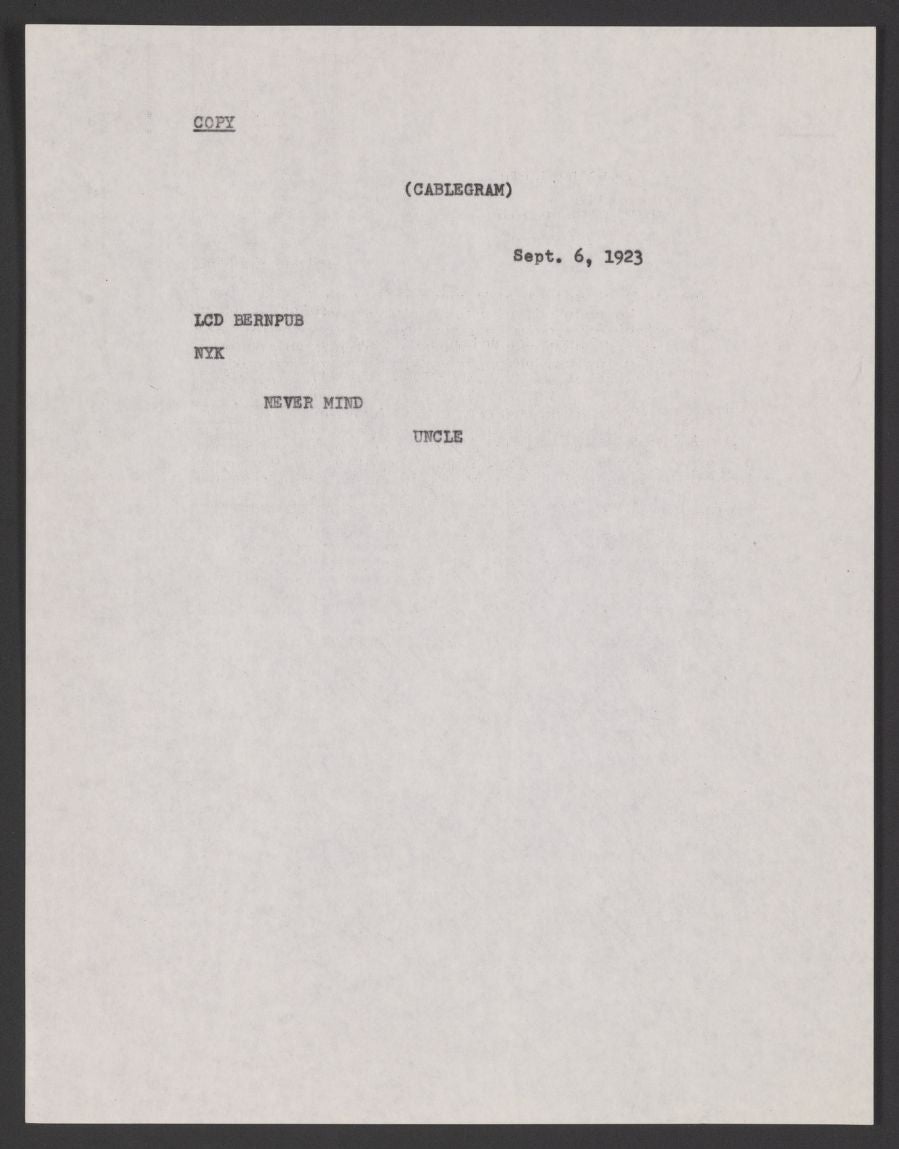

To which Freud responded:

Freud explained in a subsequent letter that he had no interest in commenting on his ideas or further explaining them to the public.

He concluded by pointing out that another royalty check was late for Beyond the Pleasure Principle:

[The publisher] could have paid already the royalties for the first half of 1923. They are 3 months due by now. It is the only book which pays.