The simple way to let consumers judge a product before it even hits the market

The best companies focus on product and in today’s startup world, we focus a lot on product. Steve Jobs built products doing zero market research. Henry Ford famously (and controversially) said that his customers, if asked, would have wanted a faster horse. There are many visionaries out there that don’t utilize any market research, yet have created exciting, world-changing tools that we never knew we needed or wanted but for each of these wildly successful products, though, there lies an even larger cemetery of products that no one wanted or rapidly abandoned. Today, where the cost of building a product has come down significantly, a glut of products has flooded the market. Many of them die in the depths of the interwebs, buried forever, like the 1996 Space Jam website. So, how do we gauge consumer interest in product? How do we separate an iPod from a Newton?

The best companies focus on product and in today’s startup world, we focus a lot on product. Steve Jobs built products doing zero market research. Henry Ford famously (and controversially) said that his customers, if asked, would have wanted a faster horse. There are many visionaries out there that don’t utilize any market research, yet have created exciting, world-changing tools that we never knew we needed or wanted but for each of these wildly successful products, though, there lies an even larger cemetery of products that no one wanted or rapidly abandoned. Today, where the cost of building a product has come down significantly, a glut of products has flooded the market. Many of them die in the depths of the interwebs, buried forever, like the 1996 Space Jam website. So, how do we gauge consumer interest in product? How do we separate an iPod from a Newton?

By having consumers put their money where their mouth is.

Earlier this month, we put on our second New York Crowdfunds, where Hotmail co-founder Sabeer Bhatia; Natalia Oberti Noguera, the founder and CEO of Pipeline Fellowship; and former New York Knick NBA Hall of Famer Earl “the Pearl” Monroe served as our “sharks” (experts providing insight and opinion to the audience, but with a limited voting power) along with eight early-stage technology companies. The competition, part Shark Tank, part American Idol, all capitalism—is a single elimination tournament where teams compete to win the audience’s votes. Tickets ranged from $100 down to $20, corresponding to the total number of votes one can apply. Each team had the opportunity to appeal to a variety of everyday potential consumers, and while the obvious strategy was in recruiting friends, the one-on-one nature of the competition and the sheer number of votes given (a $100 ticket received 200 votes for eight rounds), created an element of unpredictability and excitement—your typical marketplace. Though our sample size was small, most of the startups could gauge the consumer demand for their products while receiving critical, yet objective feedback.

Everyone has an idea but not everyone can execute it well

With crowdfunding, you can showcase yourself and your blue print for execution, demonstrate to your audience what you are trying to achieve, and ask them to take the risk with you. By putting their money where their mouth is, crowdfunders are more than validating your story; they are “investing” in your ability to execute. After all, talk is cheap. To avoid being discouraging, many people offer positive feedback; your idea is always “amazing” and a “game changer” when in reality you’d prefer to “fail fast” and move onto your next idea. Unfortunately this is seen in the investing community where most investors leave the door open, never giving a definitive no, since no one knows what will be a hit. To the detriment of the entrepreneur, technology startups have become akin to Hollywood. Most casting directors think you are the greatest: “You’re great, we’ll call you!” In case you become the next Keanu Reeves/Kate Hudson or Twitter/Pinterest, no one wants to be on your black list.

There’s been some controversy over Hollywood movies being funded on Kickstarter. Besides being an alternative way to raise money, crowdfunding also helps to gauge real demand for a product before it is made. Since the actual amount raised was a fraction of an actual Hollywood budget, it appears that these projects wanted to understand demand. After all, you’ve given money to a film that doesn’t exist in the hopes that it gets made. Of course, you will be there opening day when it gets released as well as feel some level of ownership! Films are expensive and filmmakers get no feedback from audiences until it flops or garners acclaim. Any opportunity to reduce risk is embraced: crowdfunding allows filmmakers to gauge demand before a single frame is shot. Likewise, we can decrease risk by understanding demand for web-based services, hard products, or other ideas before a single line of code, 3D rendering or prototype is created, respectively.

So-called demand or decision markets are nothing new: Intrade, until recently, let you place monetary bets on anything, the Hollywood Stock Exchange bets on the latest box office numbers and a star’s power, Empire Avenue is a marketplace where your social value trades, and the Iowa Electronic Markets offer a political forecasting marketplace. Even the Pentagon was considering decision markets to predict Middle Eastern political unrest until the program fell apart after Congress denounced the ability to “gamble on terrorism.”

Social Proof

What is new to these markets are our public identities. Most marketplaces have mostly unidentified participants; the Pentagon’s “terror markets” promised anonymity to its investors. In this case, the anonymity guaranteed a true value to the marketplace; otherwise, an accurate and true representative “price” for an action would never be able to be determined. Hedge funds protect their positions to stay ahead of the competition. Today, however, as social networks like Facebook provide an accepted identity, the value of crowdfunding networks is to see not only who is in the deal but for how much. Knowing Warren Buffet has the power to move markets; or understanding that having Fred Wilson in your seed round can eliminate your fundraising woes. With more commoditized capital chasing returns, social proof may have become more valuable than the actual raised capital.

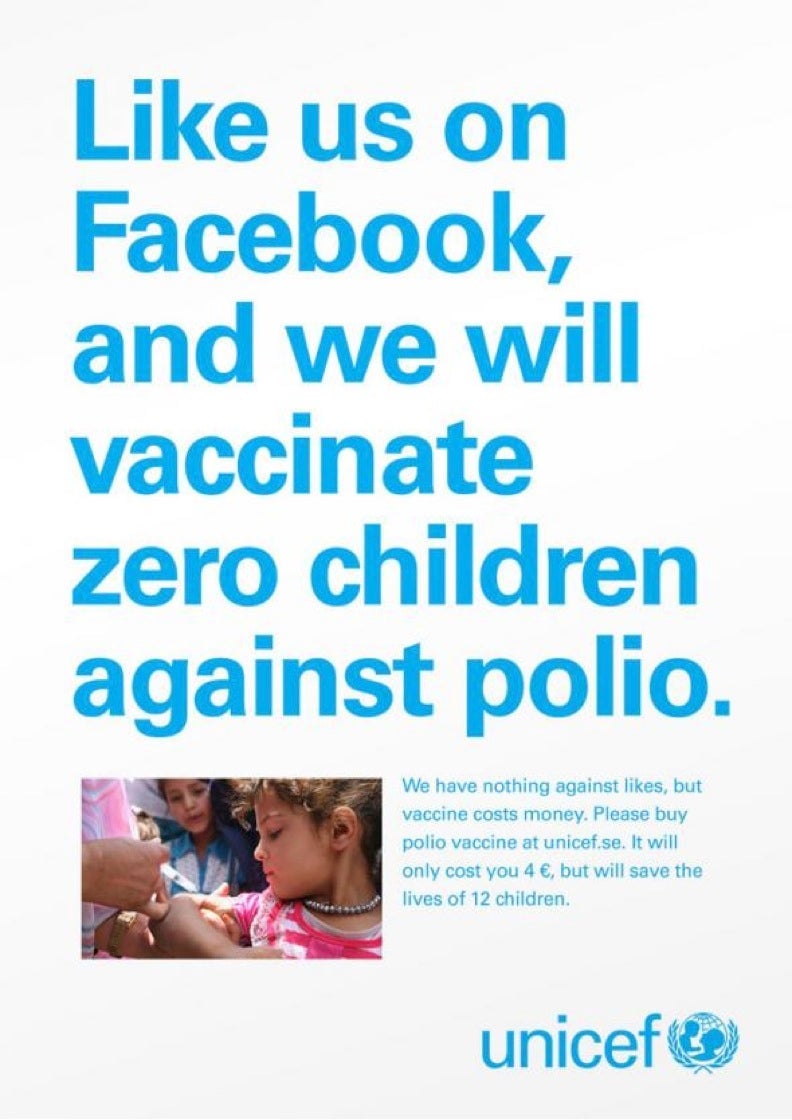

A Unicef campaign shown on the left recently went viral. While its message is true, most of the value of social media is in the identity and psychological demographics of the fan base: What kind of person is likely to support this cause? Who are this person’s friends? Do they support the cause? What are this person’s hobbies? And so on. Twitter and Facebook do not lead to transactions. Social media exists to remind you of products and brands for when you are ready to buy, not for when they are ready to sell (although sales and other specials can convince you, too). Crowdfunding on the other hand offers almost the reverse proposition: A show of support ensures that you are locked in as a buyer when you are ready to buy, even though the seller is not ready yet to sell. A Unicef crowdfunding campaign with well-defined goals, a set time period, and a clear outcome seeded via its Facebook fans would help raise this money as opposed to giving to a cause with no clear financial goals defined.

By letting you see who your fans are and how much they care (in dollars), crowdfunding replicates a film festival to movie buyers. At a film festival, the product is already created and tickets are sold on a small scale, helping Hollywood figure out how to target these moviegoers. Most Hollywood studio films that never play to an audience, until the expensive opening day weekend, hedge themselves by, for example, putting a love story in a classic science fiction action film in order to appeal to a wider audience.

Crowdfunding supporters are somewhat ruthless as many of them are not receiving a financial return, butwould like to see some kind of return on their donation, whether it be a better product or some form of success metric. These supporters will give you that critical feedback you need to bring your product to the next level of success. In my youth, I remember my mother getting a visit from an Avon Lady who dropped off a bottle of liquid skin moisturizer. One day, my dad used it prior to mowing the lawn. He told me that that product, Skin So Soft, was the best bug repellent that was all natural he’s ever used. My mom never touched it, but Avon sure did listen.

Understand Money

Crowdfunding mitigates the risk that comes along with spending millions of dollars on a new idea. One person on the hook for a million dollars is a big risk. A million people are on the hook for one dollar each is not so bad. Typically the product doesn’t come out as you envisioned, other times it comes out without functioning and still other times it just doesn’t come out. Many Kickstarter projects fall apart. Yet since the risk is low, most of the time you continue on, pat the crowdfunder on the back and tell them to keep going, as opposed to a real shark who would have asked for some kind of risk premium (similar to a discount to a convertible note for angel investors).

Like all markets, there’s an element of momentum and herd mentality, a project that has many supporters tends to beget more supporters; this behavior held true for our event as well. Social proof surfaced as well with Sabeer Bhatia appearing to be able to move markets with his opinion throughout the competition. In the end, it came down to two companies: Lucid Robotics, a company with plans to build Rosie from The Jetsons, and Modalyst, a company that aggregates small purchases from boutiques and compiles them into larger orders. But even though Bhatia offered a seed investment to Lucid, he could not take on the crowd (to his credit, he did say that Modaylst was a stronger business, but that Lucid captured his imagination more). Modalyst eventually won the crowd’s approval. (We offered no perks to any voters, just the ability to help an entrepreneur get another step closer to their dreams.) As we continue on in our journey of innovative technology and inventive systems, we have to realize that traditional models of anything, including product development and market research are becoming disrupted. We have greater insight than ever before into behavior and, like a predictive market, we can make better decisions while embracing less risk. The sheep are typically herded by the sharks. But in today’s new economy, the sheep may realize their collective power matters more.