Why is South Korea bellyaching about the yen when it’s running a $6 billion trade surplus?

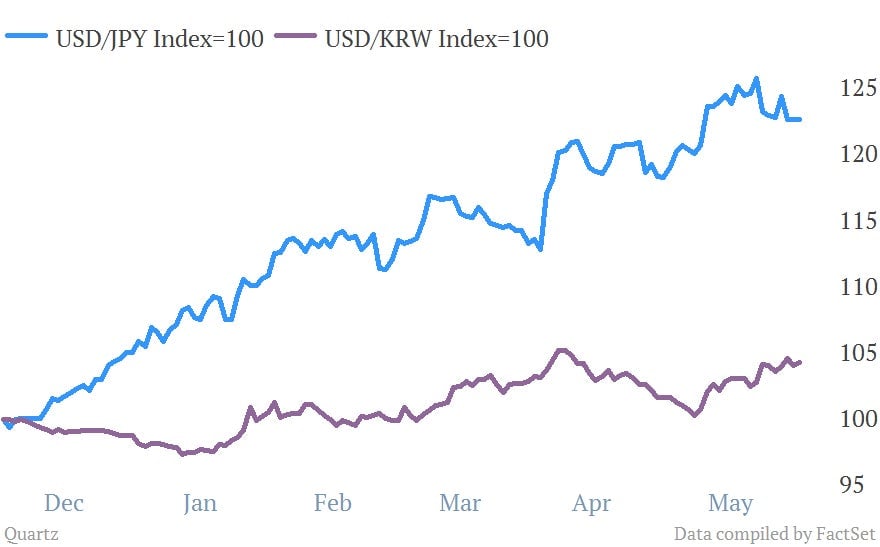

As a competitor to Japan in high-tech exports, Korea has worried for a while that Japan’s aggressive yen-weakening would undercut it. In Markit Economics’ manufacturing survey, the purchasing managers’ index (PMI), published today, Korean exporters said “the weakness of the yen was improving the competitiveness of Japanese rival manufacturers” (pdf). And over the weekend, Hyun Oh-seok, South Korea’s finance minister and deputy prime minister, railed against Abenomics to the Financial Times (paywall). “We need some kind of co-ordinated efforts to prevent these kinds of unintended side-effects from [Japan’s new] monetary policy,” Hyun said. Here’s a look at how the yen has weakened versus the dollar, compared with how the Korean won has:

As a competitor to Japan in high-tech exports, Korea has worried for a while that Japan’s aggressive yen-weakening would undercut it. In Markit Economics’ manufacturing survey, the purchasing managers’ index (PMI), published today, Korean exporters said “the weakness of the yen was improving the competitiveness of Japanese rival manufacturers” (pdf). And over the weekend, Hyun Oh-seok, South Korea’s finance minister and deputy prime minister, railed against Abenomics to the Financial Times (paywall). “We need some kind of co-ordinated efforts to prevent these kinds of unintended side-effects from [Japan’s new] monetary policy,” Hyun said. Here’s a look at how the yen has weakened versus the dollar, compared with how the Korean won has:

With more than half of the country’s GDP coming from exports, it’s not surprising that Hyun was tetchy about the yen.

But the weaker yen also made raw materials cheaper than they’ve been since July 2005. And that enabled Korean companies to slash their prices as well, said Markit. Plus, export orders still grew, though the rate of growth slowed in May.

And then there’s May trade data: the trade surplus surged to $6.03 billion in May. That’s the biggest gap between exports and imports since October 2010, and up from $2.45 billion in April. Exports to the US surged 21.6% on the same months in 2012, while exports to China, its biggest trading partner, were up 16.6%.

Korea wasn’t letting go of the blame-the-yen line, though. “Smartphone sales are pretty strong and demand in the U.S. and China is picking up…. Still, the weak yen is a big concern and our exports will deteriorate if the yen’s depreciation is prolonged and deepens,” the trade ministry said in a statement.

What gives?

For one thing, Korea’s reliance on exports is coming at the expense of its service sector, as Bhaskar Chakravorti, executive director for the Institute for Business in the Global Context at Tufts University, explains.

“Over the course of economic development, you have to transition to a more service-oriented sector at some point. [South Korea’s] leaders haven’t realized that,” Chakravorti tells Quartz. ”It’s still in the mid-50s [as a percentage of GDP], relative to in Japan, where it’s 70% of the economy.”

This is a problem because many households are still mired in debt. They need jobs to help bail themselves out, but with South Korea’s export-focused manufacturing giants, the chaebol, shifting those jobs overseas, Koreans are not getting them.

“South Korea’s productivity is extremely low. If there were a concerted push to grow the services sector it could open up a whole new [range of] jobs,” says Chakravorti.

The economy is also too disproportionately chaebol-heavy to spur economic growth through investment and hiring. Even as exports continue to boom, the fear that chaebol goods might lose out to Japanese exports is dimming household confidence and dousing consumer demand. If the chaebol aren’t confident, no one is.

But it’s easier to blame Japan than to face up to structural problems that suppress domestic demand. Until South Korea starts making some hard choices about shifting state support away from chaebol and toward services, expect more bellyaching about the yen.