With around a quarter of its population older than 60, Japan has rightly earned its rep for having the worst demographic crises in the world. But just to its north, there’s one that threatens to be just as nasty. Or even nastier—in fact, by 2045, the average age of the South Korean population will be 50, the highest in the world.

Being the oldest country on the planet…

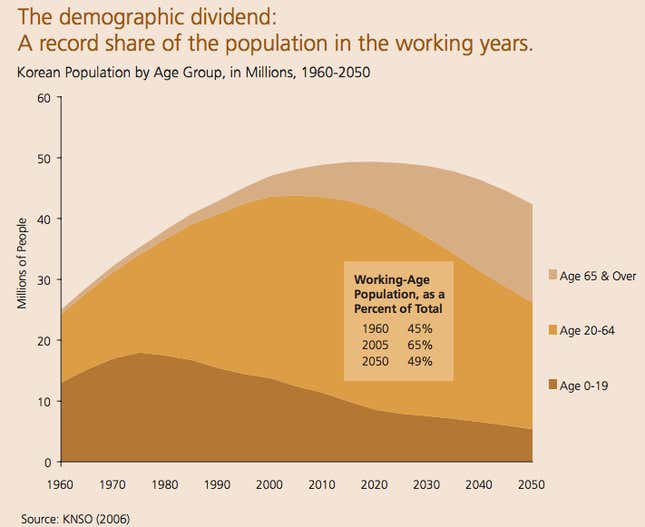

South Korea’s working-age population, as a percentage of the total, is peaking around now. By 2050, it will be back down almost to the level it was at in 1960.

Except that in 1960, almost all the non-working-age Koreans were children. In 2050, they’ll mostly be pensioners. Whereas the 60-and-older set now make up 16.7% of the total population, by 2050 it’ll have more than doubled, to 38.9% (pdf), according to the UN Population Fund. Here’s what that looks like:

This forms what Bhaskar Chakravorti, executive director for the Institute for Business in the Global Context at Tufts University, says is South Korea’s “deepest” structural economic problem. ”Pretty soon this population is going to be unproductive and 10-15% of its GDP will go toward supporting this population, according to some estimates,” Chakravorti tells Quartz.

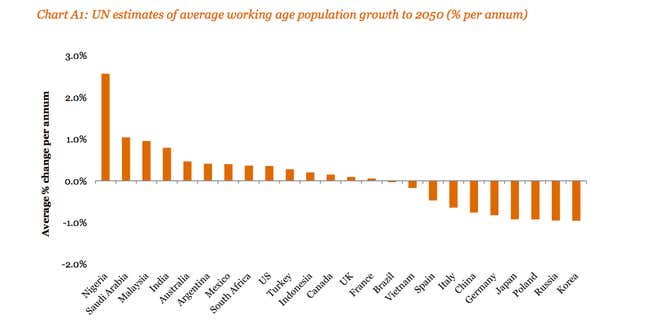

…means fewer wage-earners to pay for old people and babies.

To get a sense of what Chakravorti’s talking about, here’s a look at how fast Korea’s working-age population is shrinking compared with other countries’:

One big reason that Korea’s demographic problems are worsening so fast is that the fertility rate, once among the highest in the OECD, is tanking. In other words, Korean parents are having too few babies to replace the number of workers eventually leaving the labor force. That means fewer and fewer workers contributing taxes. And the resulting overhang of seniors will increasingly strain Korea’s public finances as the state faces an ever-dwindling supply of revenue. In fact, at the current rate, the National Pension System projects that it could go bankrupt by 2053.

But that’s really just a run-of-the-mill severe ageing crisis. And lots of countries have those. What makes Korea’s extra dire is that even though it needs more people to support the pensioners, it doesn’t have enough jobs for the young people it does have.

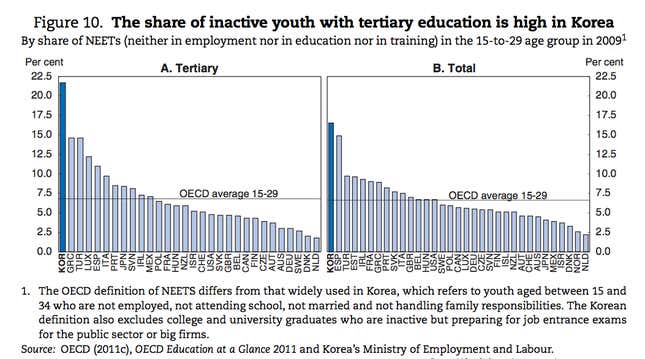

Korea’s youth unemployment rate, at 6.4%, is a lot lower than in many countries. But consider that Korea’s unemployment data also exclude what are called “Neets,” those under 30 without a job who are not enrolled in school or training programs. Around 25% of under-30 college grads (that’s the “tertiary” education refers to in the chart below) fall in that category. That puts the real unemployment for those aged 15-29 at a euro zone-like 22%, according to Lee Joon Hyup, a researcher at Hyundai Research Institute. Here’s a look at how that compared to the rest of the OECD, as of 2009:

But how can a country that needs more workers also have 22% youth unemployment?

One of the big reasons for Korea’s paradoxical labor market lies in its reliance on chaebol, big conglomerates like Samsung and Hyundai. They’ve been the engines of Korea’s manufacturing-led economic boom of the last few decades. Koreans spend some 70% of household spending on private education in order to earn their children a spot in one of the top universities—pretty much the only ticket in town to landing a chaebol job. But as the 30 biggest chaebol provide only 6% of Korea’s jobs, that single-minded focus is, for many, self-defeating. “You have roughly 300,000 college grads out of Korea competing for 18,000 jobs,” Chakravorti tells Quartz. “We’re looking at a society that has become obsessed with a handful of institutions that everyone wants to go to.”

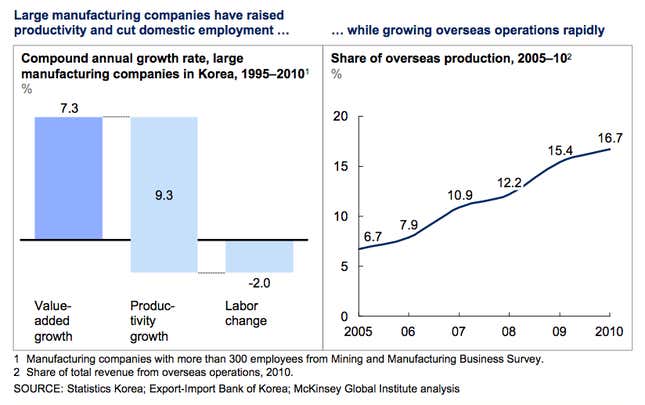

But there’s been a decline in jobs at the big conglomerates, and it isn’t a problem of robots overrunning Samsung. As they’ve become more globalized, the chaebol have been hiring more overseas—and less at home:

To be fair, it’s not that there are no jobs elsewhere in the economy. Though small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), particularly service-sector ones, hire the vast majority of Koreans, they pay, on average, just 62% of what the chaebol pay (pdf, p.22). This makes them unappealing choices for grads with freshly minted degrees from top schools. Graduates often pursue more education or become “entrepreneurs” rather than take these jobs. ”Because there are so many people graduating from university at the moment, and looking only for high-end jobs, there’s a mismatch between the job-hunters, and the positions available,” Kim Hwan Sik, director of vocational training at the Education Ministry, told the BBC recently.

Because it’s creating the wrong workers for the wrong jobs.

But here’s where another paradox comes in: Despite the Sisyphean rigor of its education system, Korea’s best aren’t suited to the jobs on offer. One reason chaebol are hiring overseas, says Tufts’ Chakravorti, is the quality of talent at home. “Among the more progressive and well known Korean companies, [the problem is that they] want to have a global footprint but they’re running out of talent, and they’ve had trouble getting the smartest in the Korean workforce to be comfortable working in a global workplace,” says Chakravorti. “That’s been an issue for a while and they haven’t quite resolved it. They’ve certainly done a good job at product design, but without the right sales and management, they’re likely to underachieve.”

All the money going to funding those pedigrees could be better spent on services—a sector that has withered as Korea has focused decades of investment on developing manufacturing and exports. Reviving Korea’s service sector, though, will also require creating opportunities for Korea’s SMEs, which generate nearly 90% of the country’s employment, according to McKinsey. That may require ending favorable policies for chaebol in order to, among other things, help boost SMEs’ pricing power vis-a-vis the conglomerates.

Of course, there’s no easy way to avert a demographic crisis as severe as Korea’s. But one way to lessen the impact of an ageing society is to make sure the young workers that you do have can, indeed, work.