In eight short stories by a Pulitzer-winner, refugees are not a “crisis” or “issue.” They’re striving, flawed, beautiful humans

In the US, two kinds of stories typically exist about Vietnam and its people: jungles and napalm, or protest and politics. A new collection of short stories by Viet Thanh Nguyen will change that.

In the US, two kinds of stories typically exist about Vietnam and its people: jungles and napalm, or protest and politics. A new collection of short stories by Viet Thanh Nguyen will change that.

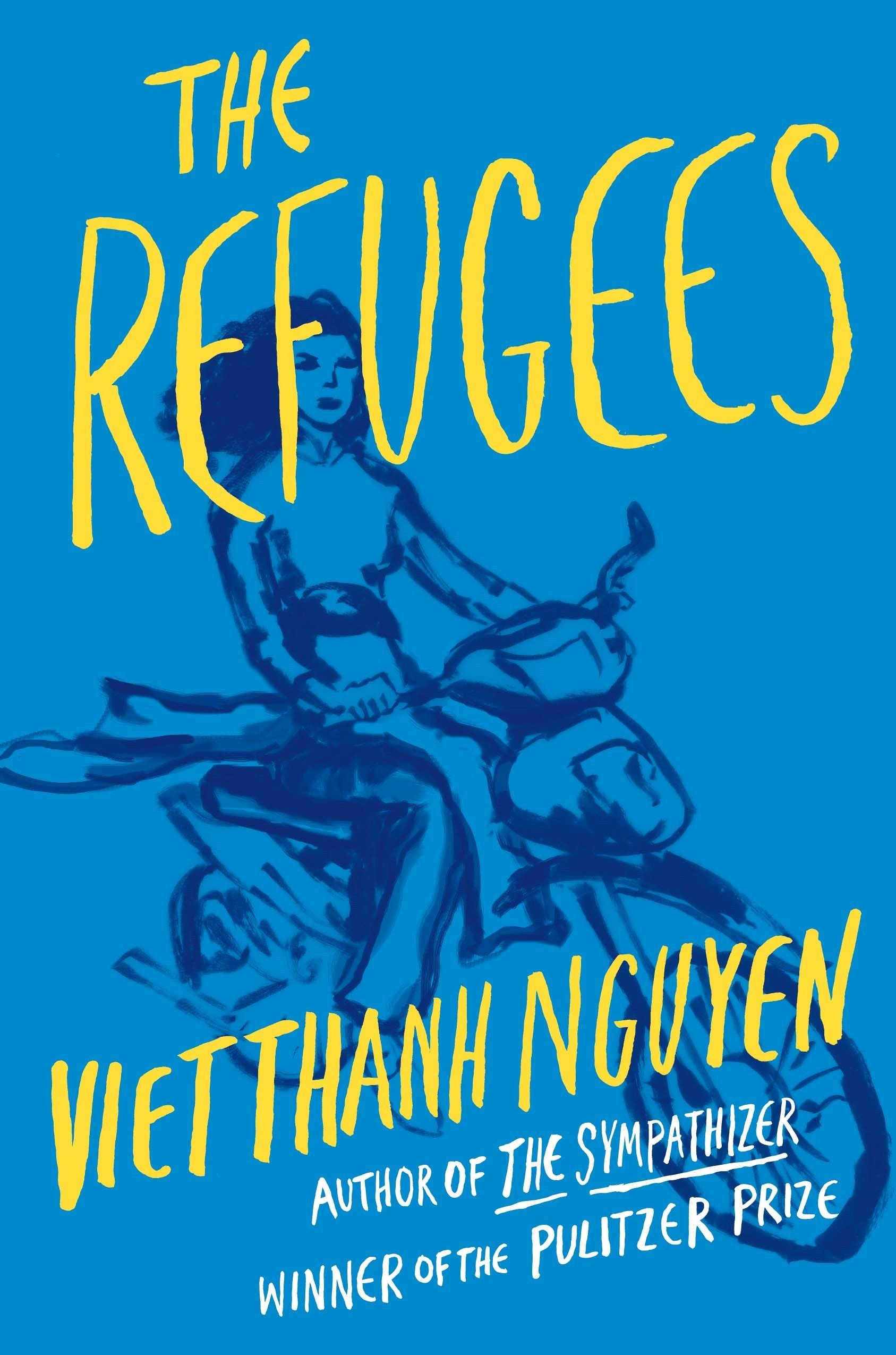

The Refugees, published Feb. 7 by the Pulitzer Prize-winner, comprises eight stories that each feature people displaced, in one form or another, by the Vietnam War, which ended in 1975. The first is about a woman visited by the ghost of her brother, who died on a tiny fishing boat crammed with refugees; the last is about two half-sisters in their twenties, one in the US and the other in Ho Chi Minh City, each a romanticized foil to the other. In between, we meet an aging professor who’s forgotten his wife’s name; a con artist who sells fake luxury bags; and a woman obsessed with raising money to take down communism.

The modern-day stories are largely plot-driven, and the book is a quick read, though a lot more sober than Nguyen’s 2016 novel The Sympathizer, which won him the Pulitzer. The characters in The Refugees are for the most part lower and middle-class Californians, who are surviving simply, and simply surviving. The reality that underlies all of their stories is that they could just as easily have not happened: For each character, their family could have not made it to the US, not found a benevolent American sponsor, not survived on the sea—not been welcomed by US refugee policies.

But this subtext is buried deep. Only one story hints at the US’s hawkish history with Vietnam, in the form of its American pilot narrator. Otherwise, the stories, first published between 2007 and 2015, are quotidian and apolitical. That’s the greatest achievement of the collection, and one that has clear resonance today as the ability of citizens from seven Muslim-majority countries to enter the US is being weighed by the courts.

Nguyen, a professor of American studies at the University of Southern California, is an expert on the implications of displacement. He fled Vietnam with his family in 1975 as a child, and settled in Pennsylvania. His nonfiction book, Nothing Ever Dies: Vietnam and the Memory of War, was also a finalist for this year’s National Book Award.

In his dedication, Nguyen writes: “For all refugees, everywhere.” That sets up a clear message for the collection: Refugees are treated like pawns, but when the geopolitical chess match with their lives is over, they make do wherever they are scattered. They make soup, they hustle, they say the wrong things to their loved ones. In the current US political climate, one that unfortunately requires us to point out the ordinariness of Americans who are Muslim, it’s a worthy reminder that refugees are children, mothers, and fathers—not just casualties.