A subscription-based news ecosystem, if you can keep it

Several forces are pushing value-added news toward subscription-based models. Seizing the opportunity will require major changes—such as developing a strong customer culture. There’s a long way to go.

Several forces are pushing value-added news toward subscription-based models. Seizing the opportunity will require major changes—such as developing a strong customer culture. There’s a long way to go.

There are solid indications that more people are willing to pay for news. This is reason for prudent optimism when contemplating the future—but a clarification is required before going further: this applies to genuine value-added/original news produced by newsrooms, not to ersatz, largely recycled, superficial commodity information. Big difference. The former is inherently expensive and difficult to streamline. The latter is cheap to produce at scale and some players in this category will continue to thrive in distributed content ecosystems, mostly on video.

Four factors contribute to the resurgence of paid-for news.

- The weakness of digital advertising for news. In short, all indicators are flashing red. Regardless of the metrics—revenue per page, per user, tolerance to ads, ad-blockers—the picture is bleak. Except for special products such as branded contents that very few organizations are able to scale at the right level, the bulk of digital ads is performing poorly.

- The hijacking of distribution platforms. Combined, Facebook and Google capture roughly 75% of digital ad spending in the United States and 95% of its growth.

- The rise of Fake News. Regardless of their actual effectiveness, the dissemination of false informations has been a highlight of the presidential campaign. Mostly spread over Facebook, the phenomenon fueled the discredit of the pervasive social network where 45% of Americans first get their news.

- The Trump Communication Machine. With the novel concept of “alternative facts,” presidential adviser Kellyanne Conway has unwittingly stressed the importance of credible information. Put another way, with people now leading the country who repeatedly lie and mislead their constituents, a large segment of the audience, regardless of political affiliation, acknowledges the need for fact-checked information.

As a result, the number of readers willing to pay for news is on the rise. Last week, discussing its quarterly earnings, the New York Times reported spectacular growth for paying readers: + 276,000 net new digital subscribers for the last three months of the year. “The single best quarter since 2011, the year the pay model launched,” according to the company. The Times now has 1.6 million digital subs who brought in $223 million in 2016 (Q4 financial statement here)—a revenue line that didn’t exist six years ago.

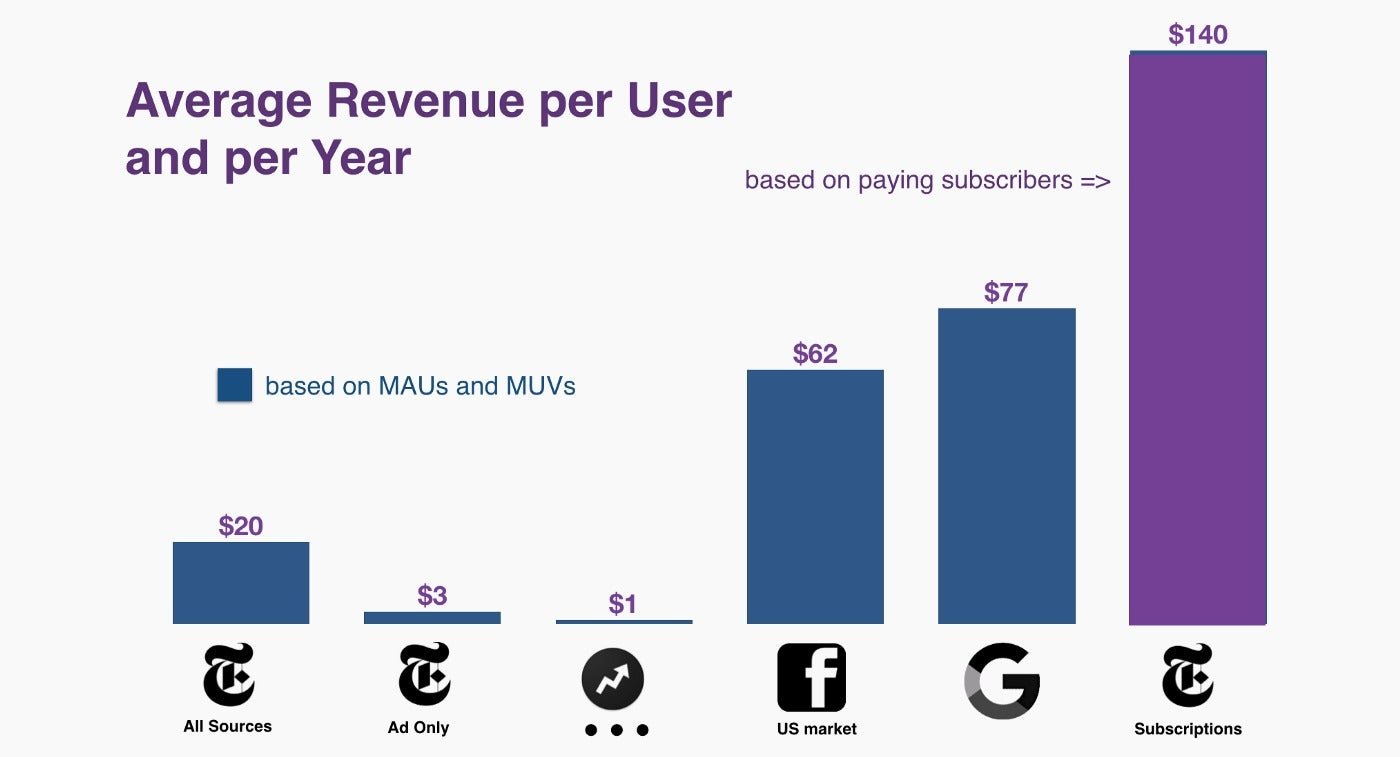

A look at the ARPU compared to unpaid models (such as Buzzfeed) and distribution platforms shows the importance of paying subscribers in the Times’ economics. The ARPU of a digital subscriber is seven times higher than the average non-paid reader of the NYT, and 46 times higher that the advertising revenue spread on the Times’ entire audience.

While precise figures have yet to emerge, many news organizations that rely on subscriptions feel the same trend. From Brexit to Trump, the rise of populism favors a flight to quality information.

This should be a cause for celebration. But it order to consolidate this shift, news organizations—especially legacy ones—need to undergo substantial transformation in the way they treat their clients.

Three personal anecdotes.

#1. A couple of years ago, while being a long time subscriber to the digital edition of Wall Street Journal, I was grossly overcharged by Dow Jones. Unbeknownst to me, of course, the company substantially raised my digital subscription by splitting and then adding back its components (desktop and mobile). I tried to investigate and quickly gave up. They lost me as a customer.

#2. Last year, I wanted to terminate my subscription to the digital version of the Financial Times. I have the utmost respect for the paper, but the ratio of cost to reading time no longer felt attractive (plus their mobile web app has fallen behind). I contacted the subscription department: “Sorry sir, we don’t allow any anticipated cancellation. Your subscription still good for, see… nine months. You’ll be able to cancel after that…” In due fairness, when I notified the FT that I won’t renew my subscription anyway, they quickly came back with a better deal (which has been readjusted upward later…). I’ll be sure to exit the FT.com when I have a chance.

#3. Last month, my NewYorker subscription purchased through iTunes stopped working on my iOS devices. I called the venerable magazine.

—Sorry sir, you got your subscription through iTunes, there is nothing we can do for you…

—Wait a minute. Where does my money goes in the end? In your account, right?…

—Sorry sir, as I said (…)

I sent an email to Apple who responded 24 hours later by the following:

Between the lines, you read: OK, let’s not waste time here; these suckers at the customers relation of the New Yorker are unable to help, let’s not put that in the way of your relationship with us Apple: you get a full refund and we’ll deduct that from our monthly payments of the New Yorker.

Call it a triple whammy: not only the New Yorker lost me as a customer (I manage to read it other ways), but they lost money on my subscription. Even worse: I might settle for the “12 weeks for 12 dollars” offer, which is a terrible deal for Condé Nast because they have to deliver a physical product for one dollar a piece.

Among multiple of my acquaintances, these three little tales where met by “Oh, it happened to me too.” I’m afraid these are not mere anecdotes, but that they accurately reflect the state of the industry when it comes to customer relations.

These brands are stuck in an antiquated “captive model” in which the customer has no choice but to surrender to their mediocre system. In doing so, they miss two crucial elements. One: the choice to get my news has never been wider; today, being deprived of the WSJ or the FT is much less painful than it was 10 or 20 years ago. Two, when it comes to customer service, me and 244 million Amazon customers, 150 million iTunes users, and 74 million Netflix subscribers have references that set a high bar for expectations.

Amazon, for instance, sees that I am a loyal customer of 20 years, with a high ARPU and next to zero incidents. Their customer service treats me accordingly whether for a refund or to return an item, even if the mistake is mine. This is exactly what I expect from a digital media company that I pay several hundred dollars a year to. Do I (or will I) miss the WSJ and the FT? Yes, but my irritation for feeling “milked” outweighs my attachment to the products.

The New Yorker/iTunes anecdote is actually the most interesting. In that case, the platform—iTunes—became the remedy to the publisher’s shortcomings when addressing my customer dissatisfaction. It is also notable because, in the near future, platforms could become a key intermediary for subscriptions because they are likely to yield much better performance. (More on this in a future Monday Note on how platforms could disrupt the paid-for model).

All of the above makes me believe—to my utmost regret—that traditional publishers might not take advantage of the rebound in the paid-for model. Amazon and others have been in business for more than two decades now. If the publishing industry has not been able to learn best practices from them, I don’t see it happening now.

I truly hope to be proven wrong.