A smart member of the global warrior elite “discovers” the next big threat

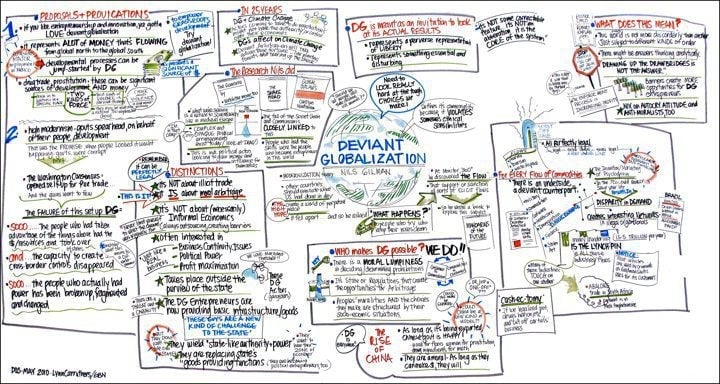

It’s not exactly a new thing in international security circles, but it seems poised to become the next big thing: deviant globalization. The concept describes the convergence of all of the types of criminal activity that flourish in the teeming underworld of black market economies.

It’s not exactly a new thing in international security circles, but it seems poised to become the next big thing: deviant globalization. The concept describes the convergence of all of the types of criminal activity that flourish in the teeming underworld of black market economies.

The idea began circulating after three Bay Area big thinkers—Nils Gilman, Jesse Goldhammer, and Steven Weber—wrote a book about it in March 2011 (“Deviant Globalization: Black Market Economy in the 21st Century“). But it generated little public attention or discussion then. At that time, global security experts didn’t yet understand the interconnectedness of so many forms of criminal and legitimate business activity, Gilman told Quartz. A Facebook page and Twitter account, @DeviantGlobalization, soon cropped up, but with very meager followings. A Nexis search generates two obscure hits.

The concept resurfaced a few weeks ago in an obscure but prestigious journal at West Point, the U.S. Army’s military academy. It described how Mexican drug boss Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman Loera has embraced deviant globalization. Loera used traditional corporate business practices to expand his trafficking network into an international empire with many profitable revenue streams. We wrote about it here at Quartz.

Now Adm. James Stavridis, one of the foremost creative thinkers among the global warrior elite, is talking up the concept, which he has also dubbed “criminal convergence.” Forget Iran, North Korea, the insurgency in Afghanistan, civil war in Syria or even cyberthreats, chemical weapons and terrorism, wrote Stavridis in a recent op-ed in The Washington Post. Deviant globalization is more worrisome.

The op-ed was based on the forward to an intriguing 275-page treatise written by Stavridis (who was the supreme allied commander for global operations at NATO from 2009 until earlier this year) for the U.S. military’s Center for Complex Operations at the Institute for National Strategic Studies. He warns, for instance, that well-worn global drug trafficking routes that are also used to move weapons, human slaves and even pirated software could soon be used to smuggle a nuclear weapon into a major city.

This convergence is what Stavridis calls “the dark side of globalization.” Bad actors in various parts of the world have harnessed cellphones, the Internet and other emerging technologies to combine their criminal enterprises into cohesive networks. “It is the merger of a wide variety of mobile human activities, each of which is individually dangerous and whose sum represents a far greater threat,” he wrote.

Stavridis isn’t the first to warn of such convergences. But he brings new urgency to the idea, warning that governments and the private sector are failing to work together to counter the problem. Gilman, one of the three men who defined the concept, told Quartz he’s glad that the concept is gaining traction. “There is increasingly a congealing realization that this topic touches on all of the issues that are animating policy—trade policy, security policy, human rights policy, cybersecurity, counterterrorism, humanitarian aid and anti-trafficking—all of the dominant issues when it comes to international security.”

Stavridis, who is known for his prescience, provides good advertising. In 2007, when he headed U.S. Southern Command, he began sounding similar alarms about another threat that no one in military or security circles was talking about: climate change.