There are many ways to look at countries. Some see connected pieces of political geography; others see ‘imagined communities’ tied together by mythical values, histories and economic pressures.

The rapid globalization of the past few decades, in part driven by and in part reflected in deep technological changes, now forces us to look at countries as “Portals” merely regulating the flow of ideas, skills, and opportunities based on fast evolving protocols.

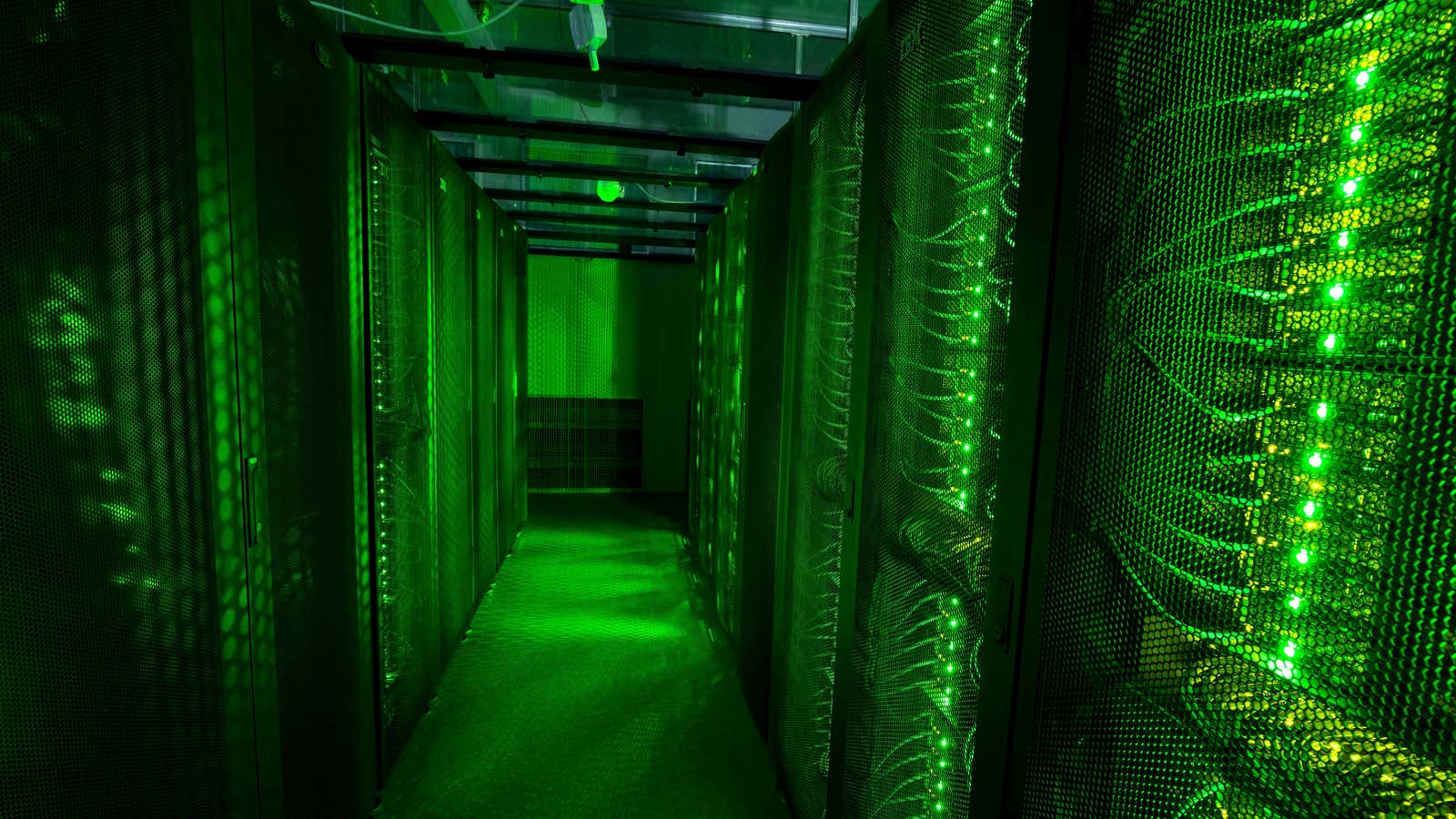

It is fitting then that one of the most apt metaphors for counter-illustrating this trend is the growing phenomenon of cloud-hosting companies offering subscribers a choice as to where their data can be hosted. After all, if you think of it, the ‘cloud’ was supposed to be the pinnacle of the internet, and the internet the very essence of ‘stateless borderlessness’, and yet here we are contending with the rise of data nationalism.

We have been here a number of times before. Just before World War One, when transcultural ideas were perceived to be subsuming national boundaries, and just before the 2008 crash, when transnational finance was held up as heralding a world where transnational corporations, not nations, formed the building blocks of the world system, prompting panicky calls for a global Tobin Tax.

Now nations are firmly back in vogue, but not in the old Westphalian, UN General Assembly, sense.

To illustrate this point, take the example of ‘maritime flags of convenience’. More than half of all marine vessels worldwide register in countries such as Antigua, Panama, Liberia and the Marshall Islands, and thus fly their flags. These tiny countries together account for nearly half of all ship registrations.

Is this just another form of the old ‘tax haven’ con of transnational finance, or something deeper?

While it is true that some ship-owners may register their ships in Liberia to evade sound regulation and scrutiny, hide assets, and even maltreat staff, just as it is sometimes the case that a politician will stash funds in the Cayman Islands solely for the purpose of hoarding ill-gotten loot, there are many occasions when arrangements very similar to the foregoing would be made in order to heighten compliance with sound law and regulation.

This is practically the same reason why many contractual parties agree to use New York and London as their jurisdiction of choice.

In fact, research shows the flexible hiring of maritime workers enabled by flying a flag of convenience is designed less to undermine worker rights but more to circumvent unsound labour immigration laws and rules in advanced economies such as the United States. Rather than spurring a competitive race to the bottom, economic actors are actually “deploying countries” to facilitate the emergence of industry models suppressed elsewhere.

Countries are not just portals. A more insightful computer metaphor says that they are “source code” for the building of new, modular, economic programs based on increasingly more creative legal and cultural algorithms.

So when courtesy of Snowden, the world discovers that the technology regulation algorithms of the United States system are buggy, they do what any good programmer does, they replace those parts. They use a data center elsewhere, even if fundamentally American technology remains at the core of whatever model they are deploying.

This is precisely where Africa comes in. It can contribute powerful, untainted, source code. In a world, where not just the US and powerful European countries, but also emerging powers in Asia, have become so paranoid that they are contaminating fundamental trust-algorithms in the pursuit of elusive security, an Africa that stands back may yet stand out.

Historically, countries that have sought to reassure their clients of firm restraint have done so simply by abjuring many of the trappings of power. For example, Switzerland decided not to have an aggressor army. The smaller, more traditional, tax havens have been careful about building their own aggressive, expansionist banks. Flag states of convenience never aspired to have giant navies.

African governments’ current incapacity, even impotence, to rig the systems of digital trust that have fueled the internet boom over the last two decades may actually be a boon in disguise: the source of genuinely trusted code. Whether it is hosting blockchain nodes or plain vanilla data centers, Africa needs to market more than its consumers. It needs to champion its rule-abiding posture, even if cynics deride it as accidental.

But there is an even more fascinating twist. African countries have all they require, including flexibilities and incentives other security-paranoid regions do not have, to create “deliberate jurisdictions” to enable an even higher level of trust.

Not only do the technologies exist for complex services serving one geographical location to operate from another, but more and more transnational legal regimes are emerging championed by the likes of the International Chamber of Commerce that offers any creative country the means to assure investors of “jurisdictional enclaves” where “best practice law” can be enforced.

The phrase “synthetic jurisdiction” might come to mind, but what intrigues me more at this stage is the notion of: “syncretic jurisdictions”. All that it takes is some creative manipulation of Vienna Convention norms and the prospect of diplomatic outposts being used as literal extensions of this “special jurisdiction” status can be brought right from Africa to the doorsteps of the powerful consumer markets of Europe and America and within the comfort zone of their investment elites. Yes, I could be talking about Congolese diplomatic facilities in Paris serving as blockchain server-nodes!

Marketing is of course the challenge, but the burden needs not exclusively fall on the African countries themselves. ‘Intel Inside’ is often seen on other people’s products. The clients of African Country-Sourcecode have as much incentive to build the brand as the African countries themselves. It is just a matter of narrative. All it takes is for the competitive advantage to be clear to the initial anchor clients.

It pays to remember that just as the State of New York was not singularly responsible for the deepening and enrichment of its arbitration and investment dispute laws, nor Panama entirely to credit for the maturing of its maritime legal system, it should not depend entirely on the leading African countries themselves to incubate the primary factors for internet innovation based on sound regulation in their territories, at home and abroad.

All they have to do is align strongly with a new narrative against the untrustworthiness of rigged internet products, and enthusiastically announce their roles as “portals of opportunities”.