How Facebook and Google could disrupt the subscription model for news

By applying their technology to the publishers’ antiquated subscription systems, the two internet giants could help create a sustainable news ecosystem.

By applying their technology to the publishers’ antiquated subscription systems, the two internet giants could help create a sustainable news ecosystem.

When you go online to book a plane ticket from San Francisco to New York, your search will typically turn up about 1.2 million flight combinations, each with a different price. Considering that 30,000 flights crisscross the United States every day, that means airlines offer a few hundred million different rates for the roughly one million passengers in the air at a given moment.

Once you’re on board, though, the service you receive is basically identical to what the passenger sitting next to you gets. Your seatmate in row 34 might have paid 20% more (or less), but you’ll never know (unless you ask her). Why? Well, she might have bought her ticket at a different time than you did, purchased it from a different website, or requested greater flexibility.

That’s the power of dynamic pricing. E-commerce has allowed this practice to spread far and wide, to many sectors that never used it before the internet.

Based on your zip code, your browser (and the cookies stored in it), and the device you use (Mac, PC, iPhone, Android), you might get a slightly different price for exactly the same item, whether it is a hotel room, an entertainment ticket or even a stapler.

The news sector has been almost untouched by this revolution. By and large, publishers have never bothered to do what airlines and other sectors have long been doing: adjusting their pricing dynamically based on what the market is willing to pay.

To be fair, the business structure of publishing, whether it is for advertising or subscriptions, is not well suited to sophisticated revenue management techniques. In the old days, between the physical newspaper product, which had only a few dozen ad positions per edition, and an approximate distribution map, the industry had no incentive to make the move. TV was faster to embrace dynamic pricing for ad sales, in part because it had hundreds of slots available over a 24-hour period and could command a much higher price per unit. It’s true that Netflix or Amazon Prime, have settled on a flat rate. But they’re still dynamic: Their price is fixed, but they offer a different product for each customer.

When publishing moved online, dynamic pricing emerged—in the form of auctions for ads. Newspaper and magazine publishers, however, lost out. They handed auction management to the emerging ad tech sector, which now captures a sizable chunk of the value chain. And they never considered how to price subscriptions dynamically and in real time.

In a previous job, I suggested my publication should have custom prices for almost every subscriber—to expand our reach and benefit from everyone’s differing ability to pay. Needless to say, the rest of the room greeted my suggestion with a strange look. At the time, I didn’t realize that the airline industry has about a hundred possible prices for each customer.

It seems there is room for improvement in the publishing world. The news industry used to pat itself on the back, saying its business couldn’t be compared to any other. That is less and less true. Like other products, news now fiercely competes for three precious commodities: attention, time, and discretionary income.

Digital publishing, especially mobile and social consumption of information, has been the great equalizer in news consumption.

On a smartphone home screen, news competes with social networks, games, and service-oriented apps for tasks like transportation and shopping. And when it comes to the propensity to pay for a news product, customers will spread their discretionary income between cell phone plans, TV, streaming services (Netflix, Amazon Prime) and a myriad of online services.

The shifts that rocked the news industry should have been sufficient to get publishers to adopt an airline-like strategy. Carriers know they have to adjust the price structure if they want to avoid empty seats. Publishers have an even bigger incentive: serving an additional digital subscriber has a marginal cost of next to zero.

Today, the dominant distribution platforms—Google and Facebook—could overhaul the subscription game.

If they are really willing to contribute to a sustainable news ecosystem, as they claim, both should allow publishers to sell subscriptions on their platforms (while collecting a fee, obviously).

Google could easily do it by adapting its Google Play infrastructure (which already sells subscriptions) to news products, à la iTunes. But instead of limiting sales to the online store, Google could make offers directly through stories showing up on Google News and Google Search. By “offers,” I mean a multitude of dynamically targeted deals powered by data points that the search engine maintains on every user.

For example, a dynamic pricing layer could make the same subscription to a news service available at $19 a month for a person in a wealthy area like the Bay Area, while some educated and curious reader in a lower-income neighborhood of Detroit would be given access to the same product at a 70% discount. All of the pricing could be sliced down to a city block by matching nine-digit zip codes to IP addresses along with individual demographic data. This is all technically doable, though it may raise privacy issues.

Facebook would have to deal with a much more complicated setup at three levels.

The first involves Facebook’s sacrosanct principle of free access to the service. If the social behemoth really wants to make a key contribution to the news ecosystem, it must allow publishers to sell their products through its system.

The second involves another foundation of Facebook: its filtering system. Without it, the Facebook Newsfeed wouldn’t perform the way it does. As I have written here several times (see “Facebook’s Walled Wonderland Is Inherently Incompatible With News“), the idea of filtering news based on a user’s profile (and locking him in a cozy cognitive bubble) is intrinsically contrary to the notion of diversified, pluralistic information.

A richer stream of information cannot reside in the regular Facebook Newsfeed, which prioritizes “friends and family” content at the expense of news. Facebook might need to put the information stream in a distinct feed, like a news.facebook.com channel, connected to a transactional system. The user would have access to it, but the information stream wouldn’t t be blended with his “intimate” newsfeed of family and friends postings.

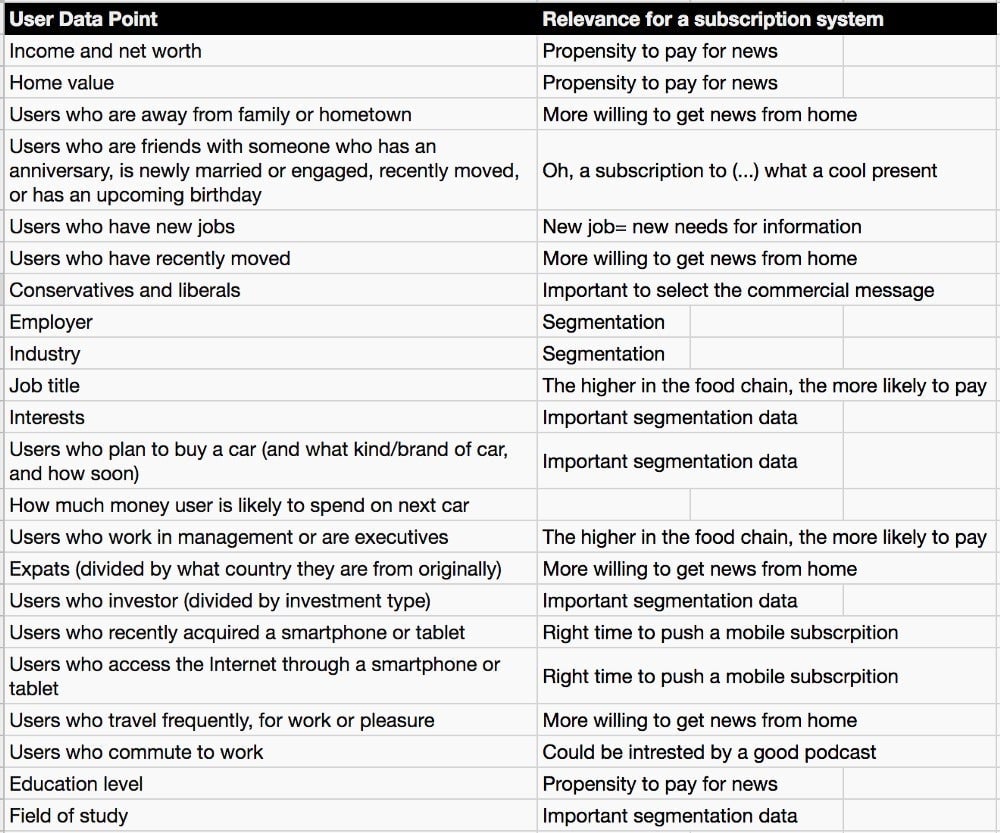

The third issue (which is also common to Google) involves using personal data to come up with a genuine, granular dynamic pricing system. In this spreadsheet, I listed the 98 data points used by Facebook to target its ads. These include the amount of money someone is willing to spend on a new car, the size and value of her home, education, job profile, and more. Below, I selected 22 indicators I found relevant from a subscription marketing perspective and added comments on why they make sense:

You see where I’m heading. By combining such targeting with a dynamic pricing system, Facebook (or Google) could vastly enhance the performance of any subscription system by giving a publisher the possibility of adjusting its pricing to the potential of a market, almost down to the individual level.

This reasoning is based on publicly available Facebook indicators; in fact, some platforms have considerably more data points. For example, the research firm Cambridge Analytica, which was instrumental in micro-targeting voters in the Trump campaign, claims to have 5,000 data points on 230 million American adults. What Facebook discloses to feed its ad machine is merely the tip of the iceberg. But even a minuscule and carefully selected set of personal data could boost the news sector’s subscription model.

This hypothetical move by the two major news distributors could be a double-edge sword. If we assume that no publishing corporation is able to single-handedly build such a large, data-driven dynamic pricing apparatus, then the industry is left with two choices.

One is to band together to build the system from scratch. There are historical precedents: In the 1960s, a group of airline visionaries put together what is called a GDS (global distribution system) that now aggregates a network of about 20 reservation systems serving about 5,000 airlines. Realistically for the news industry, it would take years to achieve an uncertain result—not to mention antitrust issues that will inevitably flare up.

The second is to make a deal with Google and Facebook (preferably both), convincing them to provide some user data and co-develop a dynamic pricing system under a long-term and reliable contract. The obvious risk of this path is that it would increase the reliance on these giant distributions platforms. But the benefit would be an immense gain in the reach and performance of publisher subscription systems, now the primary source of revenue for quality news.