After years of designing fatter birds, food companies are finally realizing chickens shouldn’t grow so fast

For decades, it’s been a race: How could we make chickens grow a lot fatter a lot faster? It was all about feeding the largest number of people. And for the most part—whether it was pleasant for the birds or not—we have gotten pretty good at it.

For decades, it’s been a race: How could we make chickens grow a lot fatter a lot faster? It was all about feeding the largest number of people. And for the most part—whether it was pleasant for the birds or not—we have gotten pretty good at it.

But now food companies are signaling they want to slow down, changing the process to make life easier for the chickens and to also make their meat taste better. Doing so, though, requires scientists dive into and tinker with chicken genetics to create a new, slower-growing model of bird. That fundamentally changes what winds up on dinner plates.

The business of creating these different models largely falls to three global breeders: Aviagen, Cobb-Vantress, and Hubbard. Each breeder owns the genetic information needed to create highly curated chicken types, each with a laundry list of traits such as strong legs, faster growth, or even “exceptional livability.”

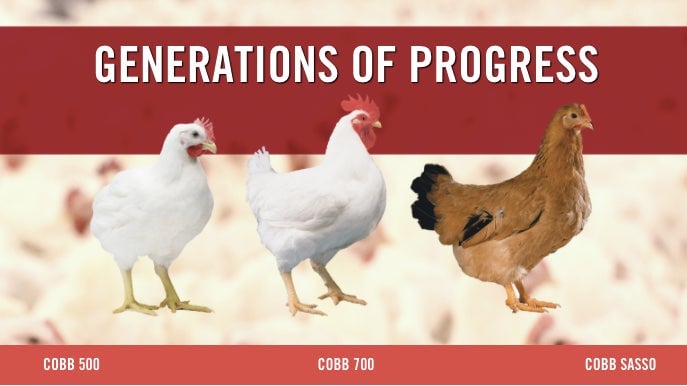

Executives at major US poultry producers—such as Tyson Foods and Sanderson Farms—then browse through breeder catalogs and pick which models they want to buy—much the same way you pick up a car model at a car lot. That means that virtually all the chickens that Americans eat have been bred specifically for them. Want a lot of breast meat? The Cobb 700 might be up your alley. Want something with lower costs that’s still pretty meaty? Check out the Cobb 500.

Once ordered, breeders supply the poultry companies with young female chickens, which are then introduced to a rooster, leading to fertilized eggs that are then shipped to a broiler hatchery. Once those eggs hatch, they are sent to the large-scale broiler farms to be raised by contract farmers.

Over time, these genetic scientists have been able to engineer chickens to fit in the modern food system, making them grow fatter faster. In the 1960s, for instance, a single bird was slaughtered at about 65 days old and weighed under 3.5 lb (1.6 kg). Today, birds are slaughtered after about 47 days and weigh more than 6 lb.

But now, this bigger-is-better style of US chicken production is beginning to wobble, thanks to businesses in the restaurant and grocery sectors.

In mid-February, Wendy’s announced it was committing to use 20% smaller chickens as a means of improving taste. That doesn’t necessarily mean the restaurant will be buying smaller breeds, but it might at some point. It puts the fast-food chain in the company of Chipotle, Panera, Noodles & Co., and Whole Foods—all of which have decided to work with animal welfare groups to switch over to slower-growing breeds. The idea is that lighter chickens will be happier because they’ll have the strength to roam around, unencumbered by their own weight.

For their part, the big breeder companies are already working to create a line of slower-growing chickens. Hubbard, for instance, already offers its “Chicken of Tomorrow” and “Label Rouge” models. “We’re ahead of the game with these genetics,” a Hubbard representative told Buzzfeed.

The National Chicken Council says there is no research in the US that shows slowing the growth of chickens improves the welfare of the birds. The trade organization has called for more studies.

Poultry producers are already working to field potential problems with the new breed. Lighter on their feet, flocks of free-moving and active chickens won’t mesh perfectly with heavier, more stationary birds, for instance. The designs of chicken housing may even have to change to accommodate the newer, slower-growing breeds.

All this has some pretty big implications for chickens, which far and away are the most slaughtered food animal on earth.